Access this essay as a PDF, including key vocabulary terms and discussion questions, or read the text of the essay below.

State and local governments have primary responsibility for setting the ground rules for elections. However, state and local governments have often failed to provide equal voting rights to all citizens. When such wrongs happen, it sometimes takes protest by the public and intervention by the federal government to right them. The period from 1920 to 2000 was marked by such activism and action, leading to constitutional amendments and federal legislation that expanded access to the ballot for racial and language minority groups and young adults.

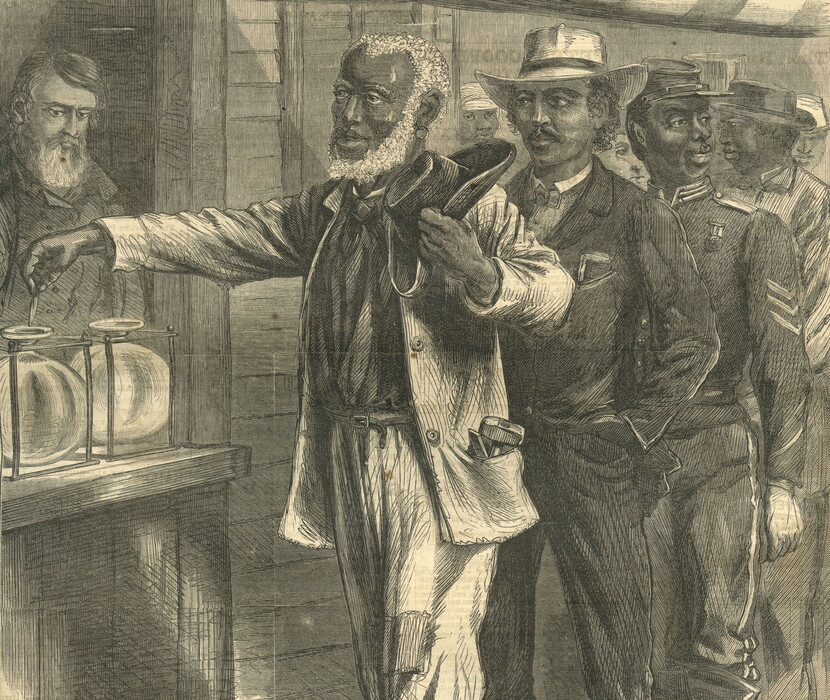

Blatant discrimination in access to the ballot has occurred throughout US history. From the 1920s to the 1960s, state and local governments used different methods to prevent Black citizens from voting. For example, Whites-only elections, known as “White primaries,” were common in the South. Native Americans were completely barred from voting in Arizona and elsewhere. Eventually, federal and state courts banned these obviously discriminatory practices. But state and local governments continued to use subtle yet effective strategies to exclude voters of color. These strategies included, among other things, poll taxes and literacy tests.

The 1950s and 1960s saw an increase in activism for full voting rights for all citizens. By 1964, this activism led to the passage of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution, which banned poll taxes in federal elections. Still, literacy tests and similar tools to exclude people from voting persisted. And efforts to give all citizens access to the ballot were met with sharp resistance, even violence. During Freedom Summer, a 1964 project aimed at registering Black Mississippians to vote, activists were beaten and murdered. In the spring of 1965, leading civil rights groups organized a fifty-four-mile march for equal voting rights from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, the state capital. As protesters crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to begin their journey, they were violently attacked by state and local police officers. This incident, which occurred on Sunday, March 7, 1965, is known as “Bloody Sunday.”

In response to Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon Johnson made a speech to Congress. He embraced the language of Martin Luther King Jr., declaring “we shall overcome” while calling on Congress to pass legislation that would have a true impact. Congress responded with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This act banned literacy tests and allowed the federal government to take over voter registration when local officials engaged in discrimination. The Voting Rights Act led to a sharp increase in voter registration, particularly among Black voters in the South.

The 1960s and early 1970s saw substantial activism related to another barrier to voting—age. Many states did not allow citizens to vote until they turned twenty-one. Eighteen-year-olds could be drafted to serve in the Vietnam War but were not allowed to cast ballots. This injustice strengthened the case for expanding voting access to college-age Americans. In 1971, Congress passed the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to the Constitution, which lowered the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen.

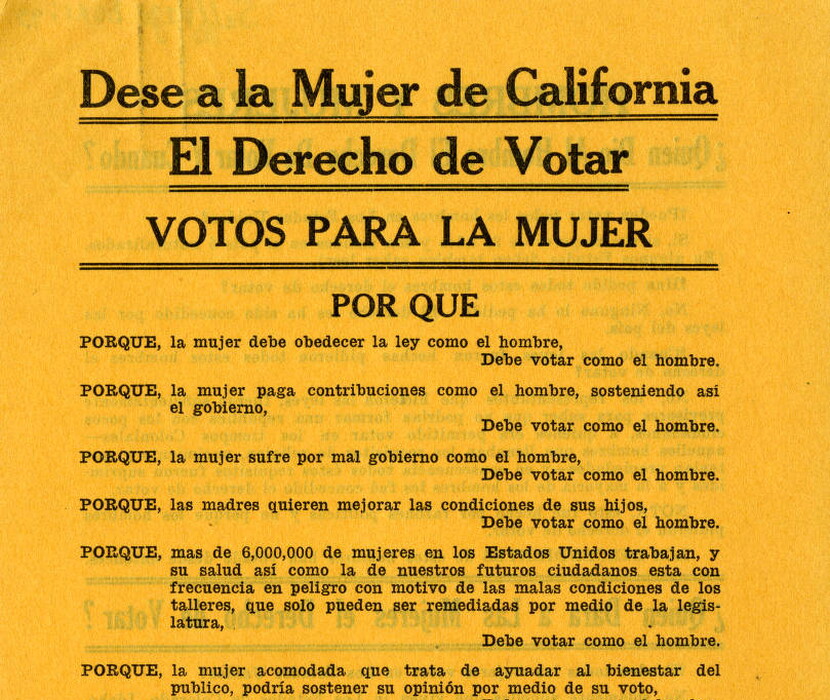

In the 1970s and 1980s, voting rights continued to expand. Amendments to the Voting Rights Act required that election materials, information, and assistance be available in languages such as Spanish, Chinese, and Navajo. And voter registration opportunities broadened for all voters in the 1990s with the passage of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA). Nicknamed the “Motor Voter Act,” the NVRA made voter registration available through state motor vehicle licensing offices. This expanded access led to not only a more diverse electorate but also increased diversity among the people elected to serve in local, state, and federal government.

While access to the vote did expand dramatically throughout the second half of the twentieth century, some individuals and groups were still prevented from voting. In 2000, the vast majority of states still had laws that prevented convicted felons from voting, in some cases even after they had served their sentences or been paroled. These laws disproportionately affected minority communities. Other problems, like the quality and the type of voting machines available, were revealed in the razor-thin margin of the 2000 presidential election. As the twentieth century came to a close, activists across the country continued to fight a state-by-state battle for voting rights for more Americans.

Michael J. Pitts is a professor of law at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. Professor Pitts’s scholarly work focuses on the law of democracy, particularly voting rights and election administration. He joined the IU faculty in fall 2006 after serving as a visiting assistant professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law. From 2001 to 2005, he practiced as a trial attorney in the Voting Section of the United States Department of Justice. He is a graduate of Georgetown Law School. Following law school, he clerked for the Honorable C. Arlen Beam, United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

Pioneering New Methods to Expand Voting, 1865–1920

by Prof. Lisa Tetrault (Carnegie Mellon University)

Access the previous essay in the series, "Pioneering New Methods to Expand Voting, 1865–1920."