Bob Stone joins the US Army Air Forces, 1943–1944

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Robert L. Stone

Lieutenant Bob Stone served as a bombardier in the 431st Bomb Squadron (Heavy), 7th US Army Air Force in the Pacific. This Spotlight is part of a series of documents detailing the experience of airmen in World War II. Click here for more information about Bob and to read more in this series.

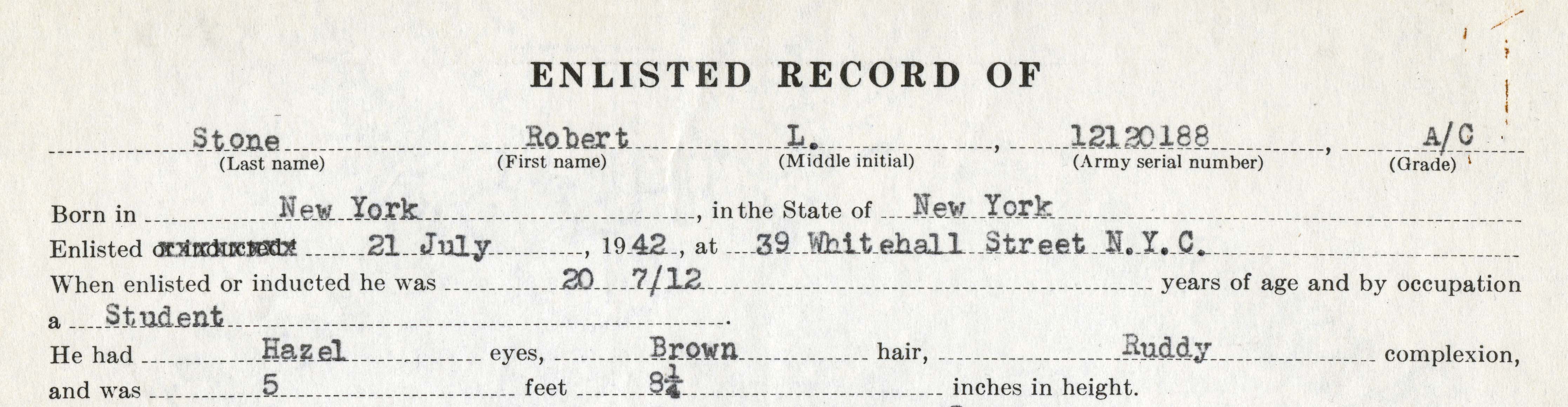

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, life changed dramatically for twenty-year-old Robert Stone and his family, as it did for all Americans. Bob finished his sophomore year at Williams College before enlisting in the USAAF Aviation Cadets in July 1942.

Due to the number of men waiting to be trained, Bob Stone did not report for duty until February 1943. He would earn the rank of officer if he completed his training. The first hurdle was to pass numerous physical and psychological evaluations in Nashville, Tennessee. Those who failed the examinations “washed out” and became privates in the infantry. On March 5, 1943, Bob wrote a long letter to his family describing the tests and the medical team’s concern about a steel plate that had been put in his leg after a car accident when he was sixteen.

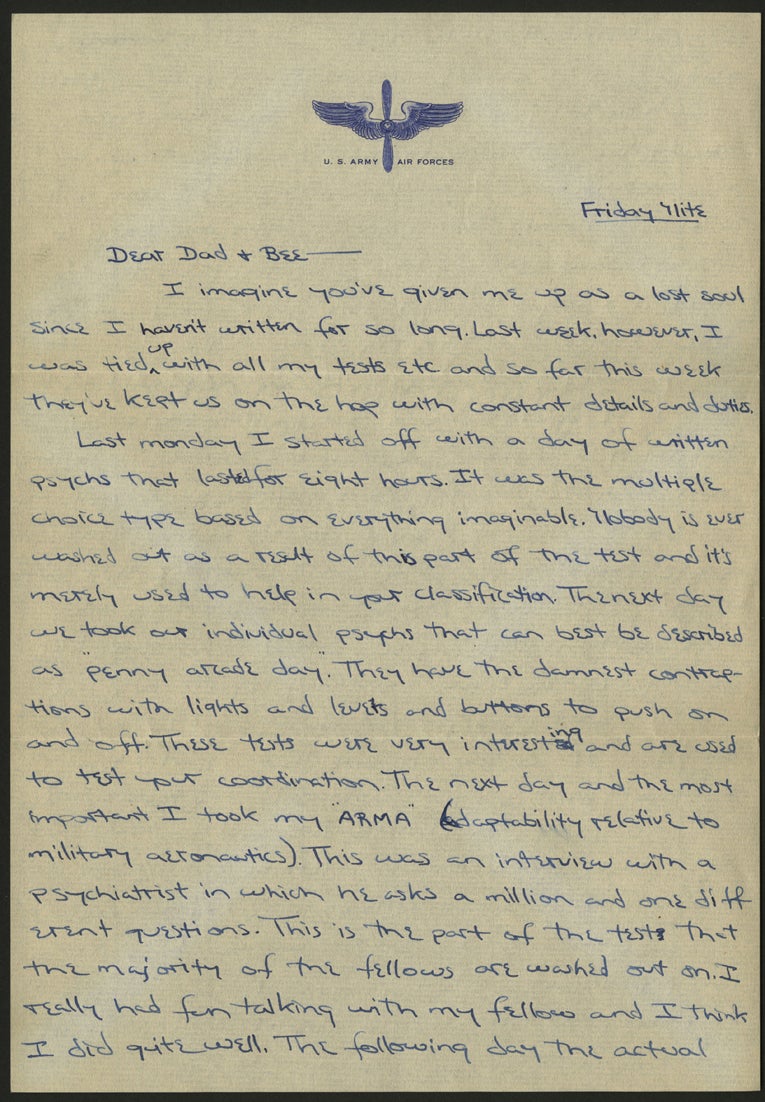

Excerpt from Bob Stone’s letter to Jacob Stone and Beatrice Stone, March 5, 1943

Last monday I started off with a day of written psychs that lasted for eight hours. It was the multiple choice type based on everything imaginable. Nobody is ever washed out as a result of this part of the test and it’s merely used to help in your classification. The next day we took our individual psychs that can best be described as “penny arcade day”. They have the damnest contraptions with lights and levers and buttons to push on and off. These tests were very interesting and are used to test your coordination. The next day and the most important I took my “ARMA” (adaptability relative to military aeronautics). This was an interview with a psychiatrist in which he asks a million and one different questions. This is the part of the test that the majority of the fellows are washed out on. I really had fun talking with my fellow and I think I did quite well. The following day the actual physical came. Never have I had such a complete going– over. The most extensive thing is the eye test in which they give you depth perception, prism divergence and convergence, as well as a number of other things. I went through the whole exam without a recheck until I came to the last room where I got a recheck on my leg cause they wanted to have it x-rayed. Had this done right away and took the pictures and the report to the captain who is the orthopaedic surgeon. He said he thought that the plate would have to come out not because anything was wrong with it but because if anything ever happened to my leg it might cause complications or some such rot. Then I reported to the flight surgeon who told me to come back the next day which I did. Went to the original captain who had eight medical officer sitting in his office like a jury. He told them about my leg etc. and the verdict was rendered not guilty—i.e. that I didn’t have to have it out. Then reported back to the flight surgeon who said my papers were O.K. to go on to classification and that was that. As yet no word has come through but it’s not too bad a sign as some fellows have had to wait as long as two weeks to get any word as it’s a long procedure. Waiting anxiously for some word one way or the other is absolute hell but there’s not a darn thing you can do about it. . . .

The number of wash outs is increasing daily and some of the kids are really broken up. After being reverted to a private they get an automatic three day pass as well as open-post every night until twelve—hardly worth it, though!!

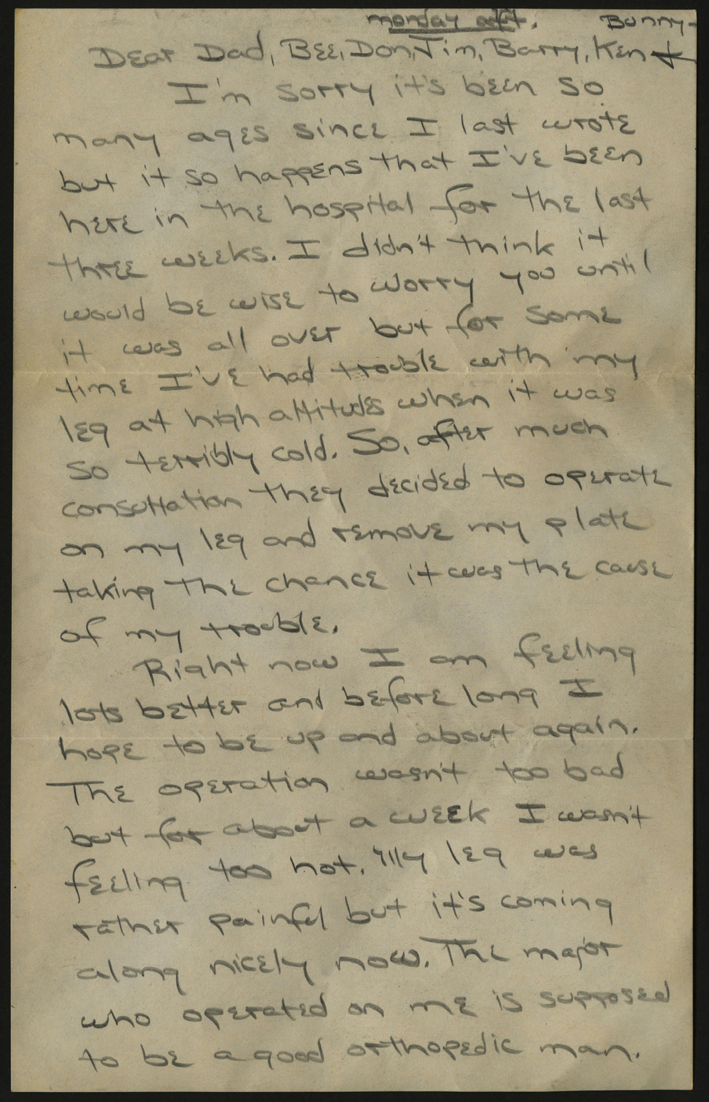

Although the medical team initially cleared him for flight, he discovered once he flew that the steel plate was indeed a problem. The military planes provided no protection from the cold temperatures at high altitudes.

Excerpt from a letter from Bob Stone to his family, February 21, 1944

I’ve had trouble with my leg at high altitudes when it was so terribly cold. So, after much consultation they decided to operate on my leg and remove my plate taking the chance it was the cause of my trouble. . . .

The one tough thing about all this seige is the fact that I was removed from my crew when I was put in the hospital. It really breaks my heart because I had such a swell gang. The boys are swell and come up to see me all the time. . . .

P. S. When they removed my plate, they found the screws to be a little loose. Consequently, it was just as well that it came out—it makes a swell souvenir! A little black metal plate with six separate screws. Just like something a carpenter would have.

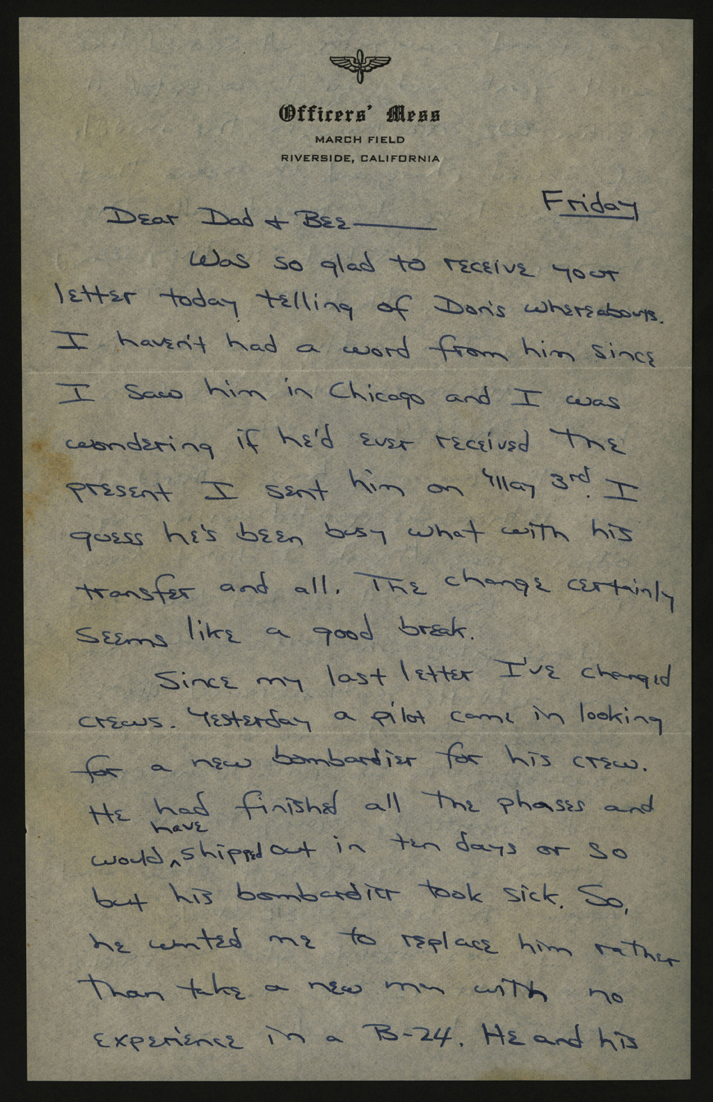

Bob’s surgery delayed his deployment. While he was recovering, his flight crew advanced without him, and he was forced to wait for a new assignment. The first replacement crew he was assigned to was less than ideal, and he was happy to be assigned to “Pop” Elkins’s crew in May 1944.

Excerpt from a letter from Bob Stone to Jacob Stone and Beatrice Stone, May 12, 1944

Yesterday a pilot came in looking for a new bombardier for his crew. He had finished all the phases and would have shipped out in ten days or so but his bombardier took sick. So, he wanted me to replace him rather than take a new man with no experience in a B-24. He and his co-pilot and navigator all seemed like swell gents and so I accepted the position. We are now put back in the middle of second phase, and it means that I won’t have to repeat all the boring ground school ect. They seemed very anxious that I join the crew and I’m mighty glad I did. will write more when I get to know the fellows better.

As you may have gathered I was rather disappointed with my other crew, although I didn’t know them too well. I had two flight officer pilots who were quite young and a little scatter-brained. Most of the kids who are coming in now seem to be quite immature and surprisingly young. To have gotten on my present crew would appear to be a swell break.

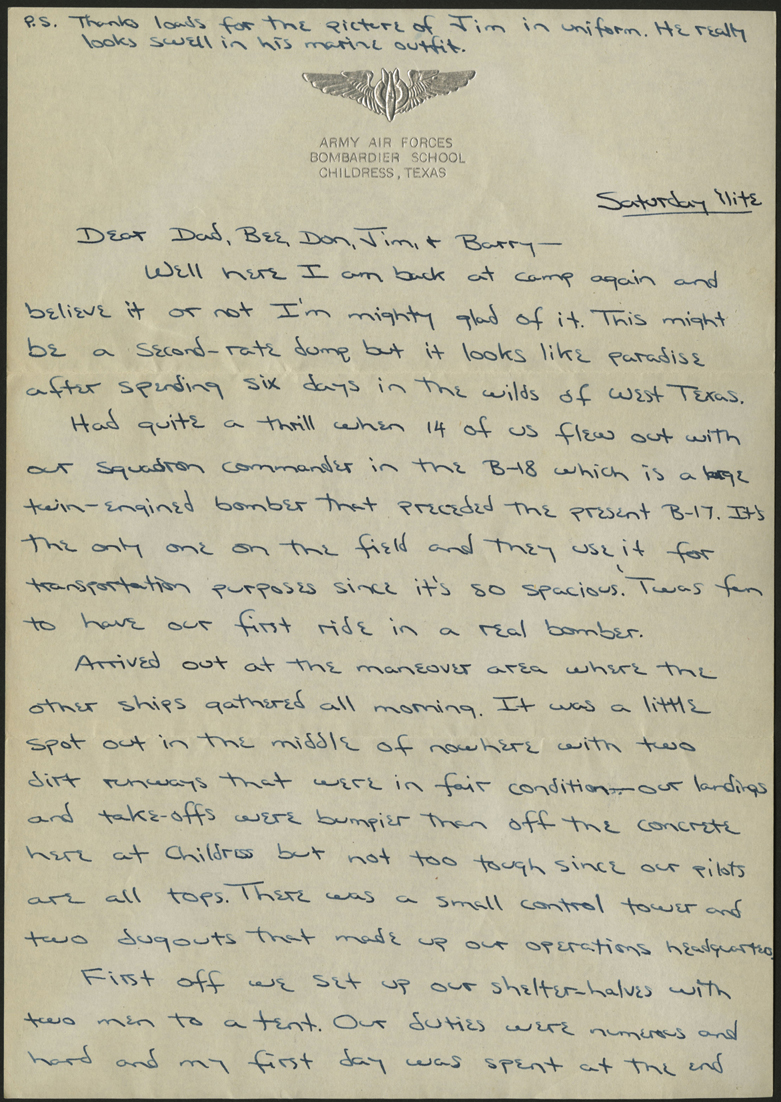

Due in part to his extended time in the hospital, Bob’s training spanned a year and a half and six army bases: Nashville, Tennessee; Ellington and Childress, Texas; Wendover Field, Utah; March Field, California; Hammer Field, California; and Oahu, Hawaii. In addition to teaching the essential skills needed to be an airman, these schools often prepared men for war in an unexpected way.

Between December 1941 and August 1945, the Army Air Forces had 52,651 airplane accidents in the continental United States that were not related to combat. Many of these crashes occurred during training and drove home the dangers of air force duty. While Bob was training in Childress, two such fatal plane crashes happened in one day.

Excerpt from a letter from Bob Stone to his family, September 25, 1943

Great sorry came over the whole camp when our squadron commander announced that one of our planes had been lost in an accident on the way to maneuvers. One ship came up under another and it’s props cut the tail fins off the other ship. The AT-11 is a twin finned ship and so the pilot didn’t have any control over his plane and it went right to the ground without a chance for safety. Our hearts were saddened when he announced the death of all the men—two cadets, the pilot, and the crew chief. . . .

After supper the camp was hit by the greatest blows any of us had ever received. We were playing ball against the officers out on the landing field. Our squadron commander, who’s one of the greatest guys you’d ever want to know, and a major who was the head of our maneuvers, were buzzing around the vicinity in a little basic trainer that we had along to go for the mail every day. All of a sudden the ship made a sharp turn about 200 ft. above the ground and went into a spin when the engine stalled. The wing flew apart like paper in mid air and the ship crashed into the ground. It was horrible when it immediately broke into flames right on the end of the runway not 300 yards away from us. Of course, both of the poor devils were killed instantly as the plane burned to a cinder before our very eyes. It was horrible and at first we couldn’t believe what had happened although we saw the whole thing unfold before us.

This was a tragedy that left the camp deep in sorrow and mental dejection. There was just nothing to say since we’d all seen it happen and it was nothing but an indescribable catastrophe. One of the pilots tried to say a few words to us but he choked up and had to stop so we all dispersed and returned to our tents in silence. Everyone was deeply affected by the blow of such a loss as was that of Lt. Sayer. All of us, both cadets and pilots were crazy about him since he was a real square guy. Because of his eagerness our squadron is admitted to be the best on the line. Actually, Lt. Sayer died a Captain since his promotion came through the day following his death. He was a fellow who would go far in the army because of his likable personality and ability to get things done the way the higher ups wanted. He was so close to several of the pilots that a few of them were broken up as much as if one of their own family had passed away. This was a tragedy that only a long time will erase from our memories. Our squadron will never be the same!