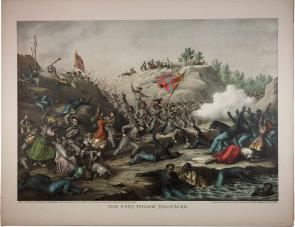

The Fort Pillow Massacre, 1864

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Mack J. Leaming

"Among the stories of the stormy days of the Republic, few will longer be remembered than the heroic defense and almost utter annihilation of the garrison of Fort Pillow."

—Mack J. Leaming, April 1893

On April 12, 1864, fifteen hundred Confederate soldiers led by General Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked the 567 Union troops stationed at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. Fighting raged until a truce was called at 3 p.m., but despite being greatly outnumbered, the Union troops refused to surrender. The Confederates renewed their attack at 4 p.m. and quickly overwhelmed the garrison. Nearly 300 Union soldiers were killed. The Confederates suffered only fourteen deaths.

The attack on Fort Pillow fell on the third anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the start of the Civil War. Many believe that Forrest and his men wanted to punish, not just defeat, both the African American soldiers and the white men from Tennessee fighting on the side of the Union who were based at Fort Pillow. According to eyewitnesses, Confederates murdered Union

prisoners, including some who were wounded, after the fort had been taken. Despite the carnage, Fort Pillow was of little tactical significance and General Forrest abandoned the fort the next day.

prisoners, including some who were wounded, after the fort had been taken. Despite the carnage, Fort Pillow was of little tactical significance and General Forrest abandoned the fort the next day.

The events were soon called a "massacre," and the US Congress investigated the reports. At the congressional inquiry, witnesses stated that most of the wounds suffered by Union soldiers targeted the torso and head, while battle wounds usually occurred to the limbs. Of the 300 Union dead, close to 200 were African American. While 70 percent of white soldiers survived, only 35 percent of African American soldiers survived. But the massacre did not deter black troops from serving in the Union Army. "Remember Fort Pillow" became a rallying cry for African American soldiers.

First Lieutenant Mack Leaming served in the 13th Tennessee Regiment in the Union Army. As the highest-ranking officer in his regiment to survive, Leaming wrote his regiment’s official report of the battle. Nearly thirty years later, he wrote a vivid seventeen-page account of the battle and its aftermath. It stands as testimony to the brutality and ruthlessness of the battle.

Excerpt

From where I fell wounded, I could plainly see this firing and note the bullets striking the water around the black heads of the soldiers, until suddenly the muddy current became red and I saw another life sacrificed in the cause of the Union. Here I noticed one soldier in the river, but in some way clinging to the bank. Two confederate soldiers pulled him out. He seemed to be wounded and crawled on his hands and knees. Finely one of the confederate soldiers placed his revolver to the head of the colored soldier and killed him.

A lengthy excerpt is available here.