A Right Deferred: African American Voter Suppression after Reconstruction

by Marsha J. Tyson Darling

In the United States, voting is a constitutionally protected right and an essential symbol of meaningful political participation in our nation’s electoral processes of governing. The right to vote and to have one’s vote count toward one’s political interests are essential aspects of citizen engagement in participatory democracy. Voting is the key to citizens participating in “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” As such, voting acts as the guardian of the exercise of nearly every right we have in American society. Without the right to vote, or to vote in a manner that enables civic participation by individuals in marginalized social groups, citizens are without a compelling voice in advancing their interests. Further, citizens are unable to use their vote to assert political independence and influence the course of events that impact their lives and the communities in which they live. This essay offers teachers and students a brief overview of the challenges African American men and then women have faced in their quest to access voting rights in our nation. For many, the problems noted in this essay will come as a surprise because until relatively recently much of our received historical narrative obscured the reality of voter suppression of African Americans.

Focusing on voter suppression of African Americans after Reconstruction, I argue that although contemporary genetics research has provided us with a revelation that race is only an idea, race and its creation, racism, have been the sites of significant struggle for the exercise of constitutional rights for African Americans. While the problem of voter discrimination is as old as the nation, dating from the property requirements for voting in the eighteenth century, the suppression of the right to vote based on one’s racial identity has shown itself to be one of the most difficult challenges our nation has faced.

Students often ask, why are African Americans as a social group still so far behind white Americans if emancipation and Congressional Reconstruction (which produced significant legislation on behalf of African American progress) leveled the playing field for access to the exercise of citizenship rights (including the right to vote), civic participation, opportunities, and material benefits? We start by noting that the problem of voter discrimination has its origins in the property requirements and racial and gender restrictions for voting in the eighteenth century. By the mid-nineteenth century, the suppression of the right to vote based on one’s racial/ethnic identity intensified, and only a few northern states allowed African American men to vote. In the South as well as the Midwest many whites feared the exercise of political power by African Americans, and the opposition to black voting was strident and at times enforced with violence.

The congressional legislation that followed the end of the four bitter years of the Civil War produced a series of constitutional amendments that abolished slavery (1865), established a basis for citizenship, set down due process and equal protection of the law as rights of citizenship (1868), and granted the right to vote to African American men (1870). A Republican-influenced Congress produced the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which required the former Confederate states to give African Americans legal rights before those states would be readmitted to the Union. At the same time, documents show that some African Americans spoke with Freedmen’s Bureau officers, wrote to members of Congress, and traveled to testify at congressional hearings, urging the creation of laws that would enable them to protect their rights as the nation’s newest citizenry.

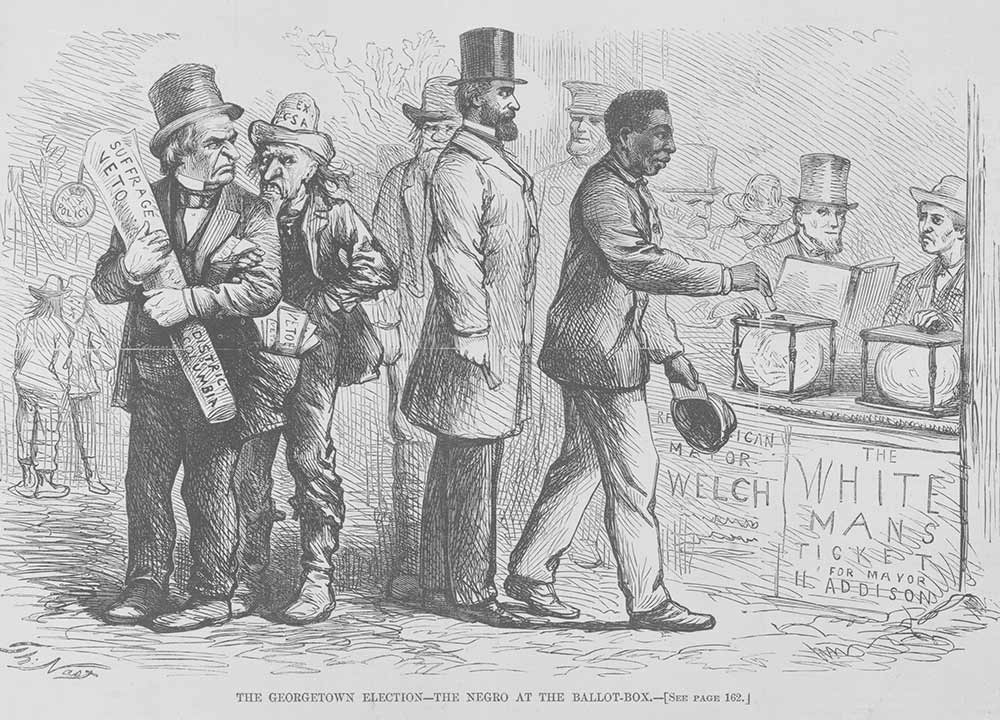

Congressional Reconstruction enabled the creation of biracial democracy for the first time in the South. With the passage of the legislation, 735,000 black men and 635,000 white men were enrolled to vote in the ten states of the Old South. ![Engraved portrait of African American members of Reconstruction Congresses [Joseph H. Rainey of South Carolina; James T. Rapier of Alabama; and Blanche K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, and Hiram R. Revels of Mississippi], New York, ca. early 1880s (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC09400.447) Engraved portrait of African American members of Reconstruction Congresses [Joseph H. Rainey of South Carolina; James T. Rapier of Alabama; and Blanche K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, and Hiram R. Revels of Mississippi], New York, ca. early 1880s (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC09400.447)](/sites/default/files/GLC09400.447cr.jpg) African American men voted in significant numbers, sending twenty‐two African American men to serve in the US Congress (two as senators), and electing many black men to state and local offices in the South. Furthermore, as all were Republicans, their votes helped to elect Union Army general Ulysses S. Grant to the presidency in 1868. Once readmitted to the Union, white leaders in southern states rewrote their state constitutions and intensified efforts to establish a rigid system of racial separation and hierarchy between whites and African Americans.

African American men voted in significant numbers, sending twenty‐two African American men to serve in the US Congress (two as senators), and electing many black men to state and local offices in the South. Furthermore, as all were Republicans, their votes helped to elect Union Army general Ulysses S. Grant to the presidency in 1868. Once readmitted to the Union, white leaders in southern states rewrote their state constitutions and intensified efforts to establish a rigid system of racial separation and hierarchy between whites and African Americans.

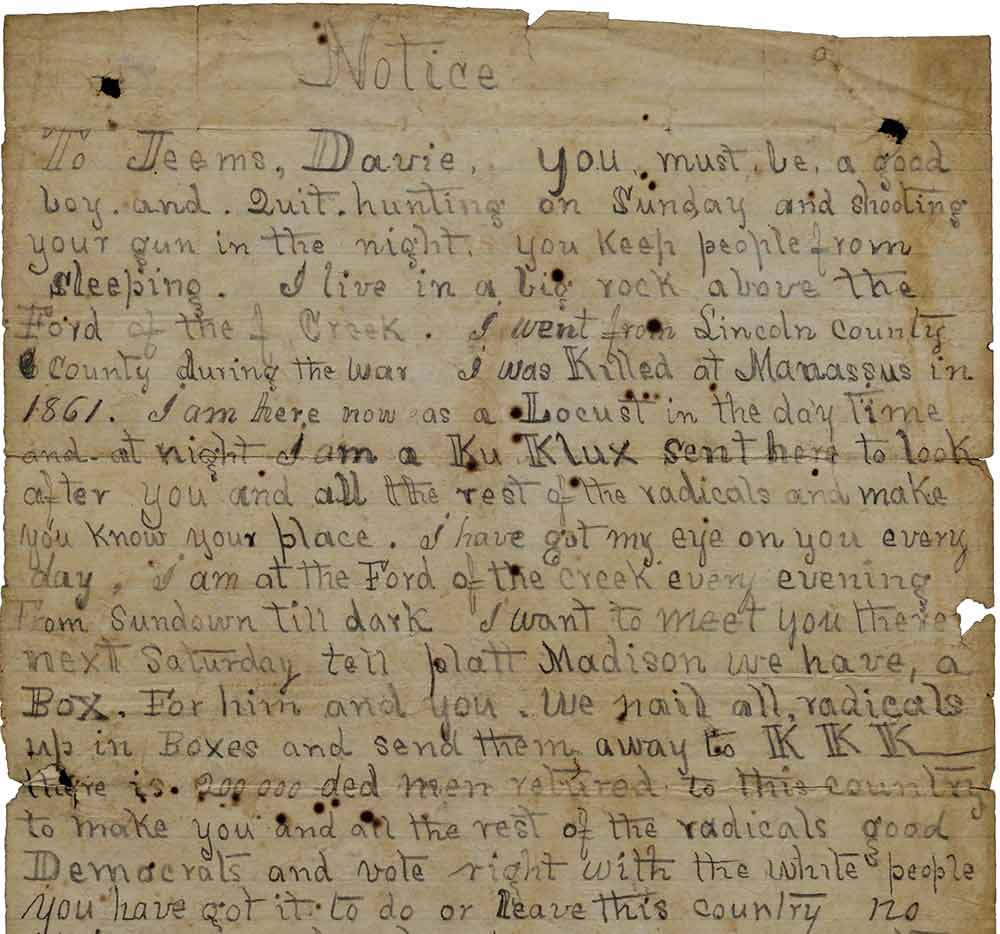

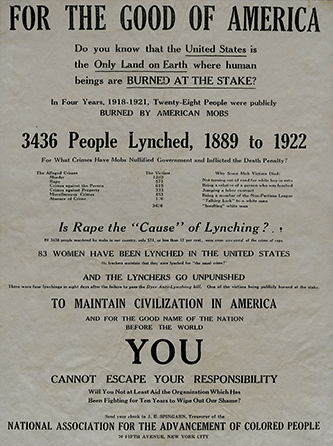

Legal and extralegal efforts destroyed biracial democracy. Southern whites re‐established a racial caste system, enacting laws like the Black Codes to put and keep African Americans separate and unequal. At the same time, extralegal acts, including widespread white mob violence and lynching of black men, the rape of black women, and even the murder of black children, were rampant and went unprosecuted. The Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacy terrorist organization formed after the Civil War, used violence as the chief means of intimidating African Americans. White opposition to African American rights and progress in the South and Midwest took the form of anti-black race riots in which individual African Americans were targets of racial violence, and sometimes entire African American communities, like Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Florida, were attacked and destroyed.  Hence, the assault on African American constitutional and social rights took many forms in the South, some physically violent, some politically and socially disempowering, all with the goal of denying African Americans self‐governance and access to legal redress for wrongs committed against them.

Hence, the assault on African American constitutional and social rights took many forms in the South, some physically violent, some politically and socially disempowering, all with the goal of denying African Americans self‐governance and access to legal redress for wrongs committed against them.

Disfranchisement of African American voters was a chief goal of white supremacy advocates in the South, and voter suppression was the means. White legislators wrote laws that employed the use of the racially restrictive all-white Democratic primary election; they also imposed literacy tests and an understanding clause, the payment of a poll tax, the grandfather clause, property qualifications, and disfranchisement for minor criminal offenses, committing outright fraud and ballot box stuffing in areas where African Americans attempted to vote. Voting was everything for members of the African American community like Bishop Alexander Walters who in 1909 insisted that voting be “the badge of political equality, the insignia of one’s citizenship.”[1] However, in 1883, the state of Virginia reapportioned city districts and amended city charters to minimize or eliminate African American representation on city councils, thereby locking African Americans out of electoral representation across the state.[2] The use of gerrymandering—drawing voting district lines to ensure vote dilution of minority voters—has over the course of many decades become a staple of white suppression of African American voters in the South and much of the rest of the nation.

The Fifteenth Amendment states that Congress has the responsibility to ensure that “the rights of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, individual states determined the specific qualifications required to be able to cast a vote. Southern states used their authority to disfranchise the majority of African American voters. For instance, following the defeat of the Federal Elections Bill (1891), an attempt by Congress to prevent African American voter suppression, white delegates at the South Carolina constitutional convention in 1895 were urged by the Charleston News and Courier to support whatever extreme measures were necessary to ensure the widely understood white supremacy goal to “reduce the colored vote to insignificance in every county in the state.”[3] One southern state after another disfranchised African American male voters, with the result that following African American George H. White’s one congressional term representing North Carolina only a handful of African American men were elected to federal office between 1929 and 1958, and this in locations like Illinois, New York, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. In Mississippi, where almost 70 percent of black male voters were registered to vote in 1867, only 9,000 of the 147,000 African Americans of voting age were allowed a qualification to vote in 1890. In Louisiana, where after the Civil War African Americans made up 44 percent of the registered voters, the disfranchisement was even more extreme: by 1920, the black vote was reduced from 130,000 registered African American male voters to 1,342, a mere 1 percent of voters.[4]

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the United States Supreme Court handed white supremacy advocates in the nation the legal ruling that permitted whites in the South, as well as many in the North, to legally assign African Americans to a permanent second‐class caste system of “separate and unequal” Jim Crow segregation. The Jim Crow system of separate and unequal access extended to segregated public accommodations, schools, trains, buses, streetcars, churches, hospitals, toilets, water fountains, theaters, parks, steamboats and ferries, bars, restaurants, cafes, cemeteries, telephone booths, and gambling halls. The intention and result was the total separation of whites from blacks, and the creation of gross political, economic, and social inequality for people of color during the decades when the nation’s Industrial Revolution created a prosperous middle class of white Americans.

It is important to remind students that disfranchisement in the former Confederate states and Jim Crow segregation were imposed on blacks not because African Americans lacked ambition. Indeed, there were African American institutions capable of training effective leaders, and self‐help traditions that dated back to the mutual aid, benevolence, educational, church-building, and publishing activities of free black communities before the Civil War.  After Reconstruction, African American organizations were founded to work assiduously for civil rights and women’s rights for African Americans, including the National Federation of Afro‐American Women (Boston, 1895), the National Association of Colored Women (Washington, 1896), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, 1909), National Urban League (NYC, 1910), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE, 1942), and still later, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC, 1957), the Student Non‐Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, 1960), and the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party (MFDP, 1968).

After Reconstruction, African American organizations were founded to work assiduously for civil rights and women’s rights for African Americans, including the National Federation of Afro‐American Women (Boston, 1895), the National Association of Colored Women (Washington, 1896), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, 1909), National Urban League (NYC, 1910), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE, 1942), and still later, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC, 1957), the Student Non‐Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, 1960), and the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party (MFDP, 1968).

The challenge to counter African American voter suppression preoccupied African American civil rights advocates who carefully tallied the terrible social costs of exclusion from the mainstream of American progress. African American self‐help agency in suing southern states produced some positive results in the 1930s and 1940s, as some southern states abolished the poll tax as a prerequisite for voting. Still, three decades later, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia continued to require payment of a poll tax as well as other racially charged practices. For instance, in most of the South, observers noted that only African Americans were required to perform accurately on a literacy test. In Mississippi, this involved reciting a section of the state’s constitution—a requirement from which whites were nearly always exempt.

The NAACP was particularly intent on ending Jim Crow segregation and focused its energies on challenging the apartheid‐like Plessy decision that served as precedent for de jure (by law) segregation in the South. The NAACP scored some significant victories in its attack on legal segregation and discrimination. Smith v. Allwright (1944), which struck down the Texas Democratic Party’s all-white primary, was an important decision handed down by the US Supreme Court. It was followed ten years later by the watershed decision, Brown v. Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas, which did not directly challenge voter suppression. Arguing that separation based solely on race violated African American children’s Fourteenth Amendment rights, the NAACP convinced the US Supreme Court to strike a blow against the social reality of “separate and unequal” in 1954. The victory in the Brown decision galvanized progressive Americans who realized that the country had fought in two world wars to save democracy, and yet many Americans, including Jews, blacks, Latinos, and Asians, experienced physical subjugation and persecution—the lynching of African American men continued through World War II—as well as political, economic, and social marginalization.

The stark contrast between American ideals and realities troubled many, particularly those who expected more from their nation. In 1952, the Justice Department produced a report, Protections of the Rights of Individuals, which noted that “the question as to the right of Negroes to vote involved twelve Southern states . . . and virtually none was permitted to vote in the primary election(s).” [5] When President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law, it empowered the US Justice Department to pursue litigation on behalf of securing voting rights for African Americans. At the same time, civil rights activists produced a movement that pressured everyday Americans, the Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court to remove barriers to African American voting and the exercise of citizenship rights.

The voluminous Civil Rights Act of 1964 sought among other things to halt African American voter suppression in the South where the majority of the nation’s voting-age black population still lived. However, it took the brutal assault on hundreds of non‐violent civil rights marchers by Alabama state troopers and Birmingham police as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to provoke a global outcry on behalf of African American civil and human rights. In response, President Johnson addressed Congress and the nation calling for voting rights legislation, resolving that “We Shall Overcome.” Within months, the proposed Voting Rights Act was signed into law. Many scholars agree that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been the most far‐reaching civil rights legislation ever enacted in the nation because of its enforcement reach.

The VRA specifically required the Department of Justice (DOJ) to send marshals to register African American citizens in those parts of the South engaged in voter suppression. Within a year, 450,000 African Americans in the South registered to vote. Furthermore, the VRA required the DOJ to create a standard for voting rights enforcement that shifted certain obligations to state and local governing institutions. Within two years, the numbers of African Americans who registered to vote in the former states of the Confederacy shot up dramatically, and African Americans and progressive whites were elected to public office-holding. It seemed to many that the nation was finally finishing what had begun during Reconstruction—the creation of biracial democracy in the South. Subsequent updates of the law provided effective intervention for ethnic minorities under the equal protection clause coverage in the Fourteenth Amendment. However, in the past decade, some justices on the high court have considered that the VRA’s enforcement provisions are outdated, and they have voted to diminish the VRA’s preclearance enforcement requirements. Unfortunately, the decision to weaken the VRA’s enforcement procedures is giving rise to unchecked voter suppression and gerrymandering against some minority communities.

In helping students to understand the centrality of voting in our society, it is crucial to reaffirm the importance of the right to vote, and the right to have one’s vote combine with the votes of others to create political outcomes that empower individuals in a constitutional democracy such as ours. Viewed in this manner voting maintains its role as the guardian of every right in our society. Voter suppression is a serious transgression against participatory democracy because it creates and sustains discriminatory harm against citizens, and fixing the consequences of past wrongs is almost always complicated and even contentious. The story of African American voter suppression is an essential chapter in American history because it speaks directly to the ongoing challenge of making democracy work for all of the nation’s citizens.

[1] Volney R. Riser, Defying Disfranchisement: Black Voting Activism in the Jim Crow South, 1890−1908 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), 9.

[2] Peter M. Bergmann, The Chronological History of the Negro in America (New York: Harper & Row, 1969), 293.

[3] Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888−1908 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 24.

[4] James H. Stone, “A Note on Voter Registration under the Mississippi Understanding Clause, 1892,” Journal of Southern History 38, no. 2 (1972): 293−296.

[5] US Department of Justice, Protections of the Rights of Individuals (Washington DC: GPO, 1952), 4.

Marsha J. Tyson Darling is Professor and Director of the Center for African, Black and Caribbean Studies at Adelphi University. She is the editor of Race, Voting, Redistricting and the Constitution: Sources and Explorations on the Fifteenth Amendment (Routledge, 2001, three volumes).