Black Lives in the Founding Era News, Week 5: Absalom Jones and Richard Allen Defend Black Volunteers in 1793 Epidemic

Posted by Gilder Lehrman Staff on Wednesday, 04/14/2021

The Gilder Lehrman Institute initiative “Black Lives in the Founding Era” restores to view the lives and works of a wide array of African Americans in the period 1760 to 1800, drawing on our archive of historical documents and our network of scholars and master teachers.

Highlighted in this weekly news post are programs, resources, and other matter related to Black Lives in Founding Era.

Black Lives in the Founding Era News, Week 5

Yellow fever broke out in August 1793 and ravaged Philadelphia for three months. Ten percent of the city’s population died. Twenty thousand people fled the city, and countless thousands of others suffered illness and hardship. The epidemic only ended with the coming of cold weather that suppressed the mosquitoes that caused it.

Volunteers were desperately needed to nurse the sick, comfort the grieving, and bury the dead. The Black community, under the leadership of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, answered the call.

Volunteers were desperately needed to nurse the sick, comfort the grieving, and bury the dead. The Black community, under the leadership of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, answered the call.

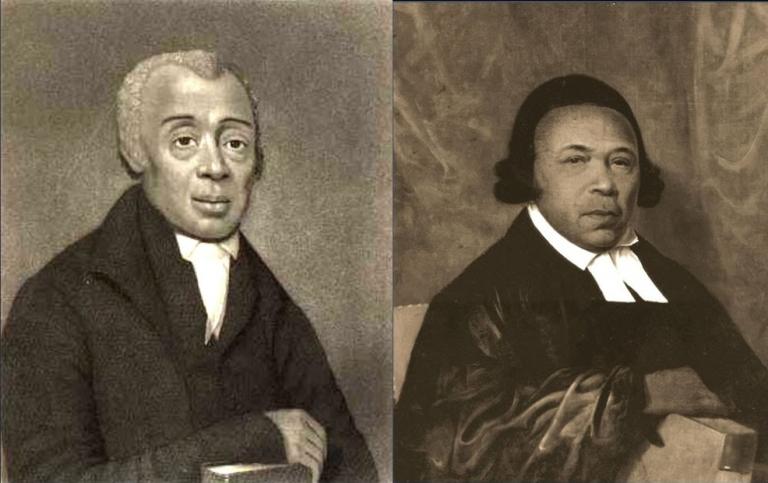

Absalom Jones was a formerly enslaved man who had worked to purchase his wife’s freedom and then was manumitted himself at age thirty-eight. He became an Episcopalian minister and leader in the Black community.

Richard Allen was fourteen years younger than Jones, and like him had been enslaved, though he had purchased his own freedom. Allen was a Methodist who would become the founder of the AME Church.

Together, Jones and Allen were co-founders of the Free African Society, a mutual aid society of free Blacks that organized the many volunteers who stepped forward to help in 1793.

Shortly after the epidemic, publisher Matthew Carey (who had himself fled the town) printed a pamphlet called A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia, which impugned members of the Black community for somehow spreading the disease, charging extortionate fees for their work, and stealing from the dead.

Shortly after the epidemic, publisher Matthew Carey (who had himself fled the town) printed a pamphlet called A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia, which impugned members of the Black community for somehow spreading the disease, charging extortionate fees for their work, and stealing from the dead.

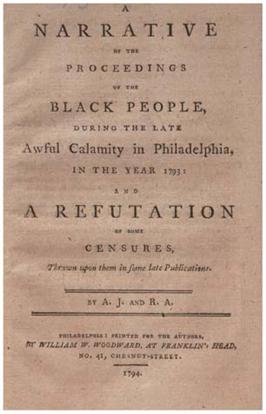

Indignant at these racist aspersions and sensitive to the need to defend their community, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen fought back. The result, in early 1794, was the pamphlet A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia. In it, Jones and Allen meticulously refuted Carey’s charges with eyewitness testimony and hard evidence, while also chronicling the many acts of mercy and generosity performed by individuals—most of them named in full—from the Black community.

Learn more about it and read a powerful excerpt from their pamphlet here.