Once they gained their freedom, Black people hoped that legal, formalized marriages would grant them the social identity and choice—in their marital partners, where they would live after marriage, and how they would structure their households—they had been denied before emancipation. They gladly chose the ways that they would celebrate their unions, and carefully attended to important details, not the least of which were the clothing items they wore at their marriage ceremonies. Both freed men and women believed that the clothing they wore when they married was an important indicator of their new status as free people who had the right to commit themselves to a legally binding and/or God-ordained union.

Their memories betray a celebration of the choice, beauty, femininity, and extravagance of freedom manifest in the ritualized clothing they wore on their special day. Some dresses were long and white, and many brides wore white veils as well—symbols of moral purity. Molly Horn recounted that “Mama bought me a pure white veil. I was dressed all in white.”[1] So too was Mandy Hadnot, who explained that she “had purty long, black hair and a veil with a ribbon ‘round de fron.’”[2] Nellie Smith added: “I wore a white dress made with a tight-fittin’ waist and a long, full skirt that was jus’ covered with ruffles. My sleeves was tight at the wrists but puffed at the shoulders, and my long veil of white net was fastened to my head with pretty flowers. I was a mighty dressed up bride.”[3] Liza Jones wore the very formalized long, full skirted, “white Tarleton dress with de white Tarleton wig.” The white dress and wig, Liza explained, were signs “you ain’t never done no wrong sin and gwinter keep bein’ good.”[4] Most clothing was special, but less ornate. Other colors and styles for bridal wear suggested freedwomen’s bridal fashion tastes were influenced by the bride’s age, previous marital status, religious beliefs, and financial assets.

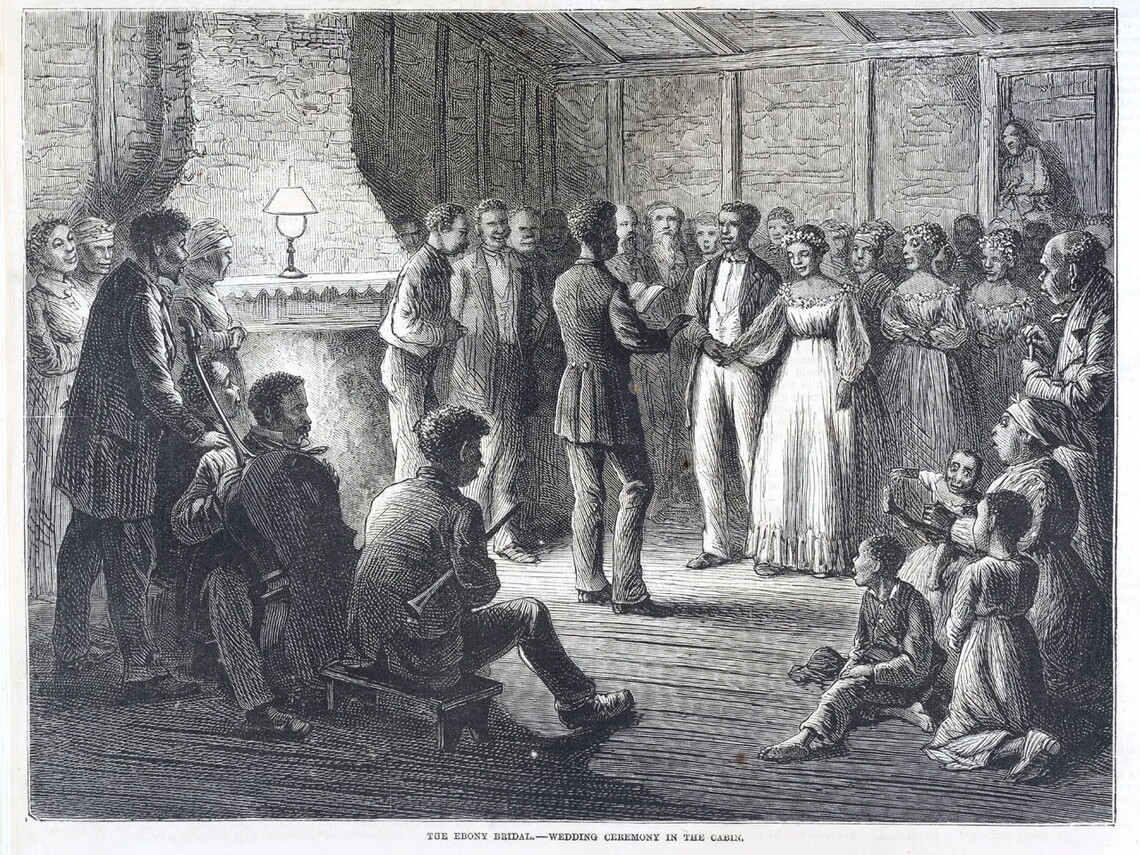

“The Ebony Bridal.—Wedding Ceremony in the Cabin,” engraving from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 19, 1871 (Image used courtesy of Library of Virginia Special Collections.)

Grooms believed that dressing for their wedding afforded them the chance to take on the look of sophisticated gentlemen. This stood in striking contrast to racist nineteenth-century stereotypes of freedmen as beastlike in manners, intelligence, appearance, and appetite.[5] Ike Derricotte sported a Prince Albert coat (long formal coat with curved tails) that he was so proud of that he intended to will it to his children.[6] Sam Bond wore a tie, white vest, and watch and gold chain, all borrowed from a local attorney.[7] Nellie Smith’s bridegroom stood at the altar in a “real dark-colored cutaway coat with a white vest.”[8] All were a sight!

The perceptions of formerly enslaved people of the importance of legal marriage linked their ideals of emancipation to other former bondspersons who had managed to gain freedom before 1865 in the US, Canada, Mexico, or beyond.[9] Hundreds of thousands, if not more, couples who had been married while enslaved, or wanted to marry after slavery ended, did not hesitate to participate in legally binding nuptials before the public. These rituals, and the beautiful clothing one wore during them, pronounced to their families, communities, and the larger world that they now had a right to claim marital relations. They asserted control over the intimate aspects of their bodies and domestic households, and to bear, take care of, socialize and maintain their children. Legalized marital rituals, they insisted, drew a line between slavery and freedom.

Endnotes

- United States Work Projects Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Arkansas Narratives, Part 3, Kindle Edition, Kindle location 3315–3320.

- United States Work Projects Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Texas Narratives, Part 2, Kindle Edition, Kindle location 1307–1311. Hereafter referred to as WPA Narratives (Texas, pt. 2).

- United States Work Projects Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Georgia Narratives, Part 3, Kindle Edition, Kindle location 3125–3127. Hereafter referred to as WPA Narratives (Georgia, pt. 3).

- WPA Narratives (Texas, pt. 2), Kindle location 2853–2855.

- See, for example, Monica L. Miller, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 77–136.

- United States Work Projects Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Georgia Narratives, Part 1, Kindle Edition, Kindle location 2703–2705.

- United States Work Projects Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Arkansas Narratives, Part 1, Kindle Edition, Kindle location 1925–1926.

- WPA Narratives (Georgia, pt. 3), Kindle locations 3125–3127.

- William Still, ed., The Underground Railroad A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-Breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the ... and Others, or Witnessed by the Author, Kindle Edition, Kindle locations 5604-9, 5896, 7702-5, 8338.

Source: Brenda E. Stevenson is an internationally recognized scholar of gender, race, family, slavery, and racial conflict. She serves as the inaugural Nickoll Family Endowed Professor of History and professor of African American studies at UCLA and she has served as the inaugural Hillary Rodham Clinton Chair of Women’s History at St. John’s College, the University of Oxford. Her published works include Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South and What Sorrows Labour in My Parent’s Breast?: A History of the Enslaved Black Family.