by Larrie D. Ferreiro

How Spain’s Contribution to the American Revolutionary War Left American History Books

English

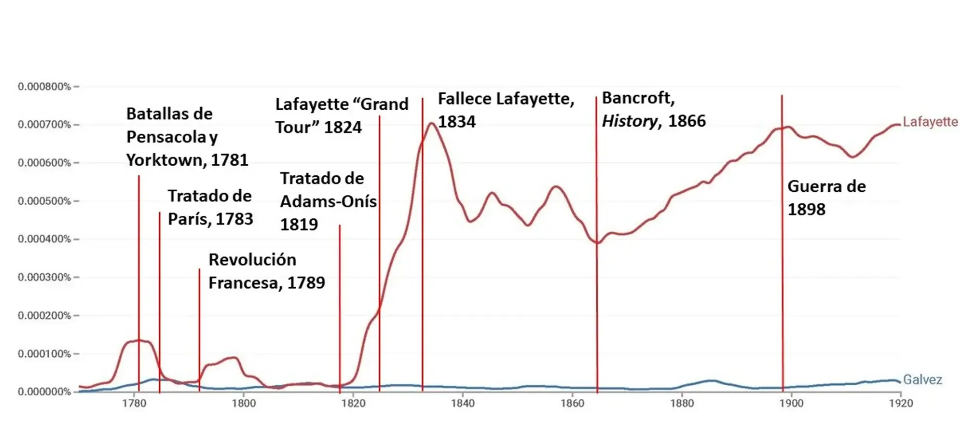

This chart shows the frequency of the names “Lafayette” and “Gálvez” used in English-language literature (courtesy of Google Ngram) from 1780 to 1920, sometimes referred to as “the long nineteenth century.”

“Lafayette” and “Gálvez” are really proxies for the recognition of (respectively) France and Spain in the War of American Independence, as both men are by far the most emblematic figures for their respective nations.

The chart shows that during the war, Lafayette (and therefore France) was more recognized than was Gálvez (and Spain); not surprising since France fought side by side with the Americans, while Spain was occupied in more distant theaters.

What is most interesting is that after the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the war and for over forty years (until 1824), the names of both Lafayette and Gálvez received approximately equal recognition for the American Revolution. The bump for Lafayette during the French Revolution reflects mostly his role in the National Assembly, in exile and as author of the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

In other words, for a long period of time after the War of Independence, histories of the war recognized both France and Spain as participants alongside the United States.

The recognition of Lafayette (and therefore France) becomes significantly elevated with his tour of America in 1824–1825, which cemented his reputation as “the hero of two worlds,” and was enshrined with his death in 1834. George Bancroft’s History of the United States (1866), by far the most influential set of history books for a hundred years, further glorified Lafayette’s role.

But Bancroft was an unabashed crusader for Manifest Destiny, the belief that America should extend its domain across the hemisphere, and the Spanish legacy was clearly an anathema to that. His History deprecated and dismissed the Spanish role in American independence. Following Bancroft’s lead, both Gálvez and Spain disappeared from American histories of the Revolution for over a century.

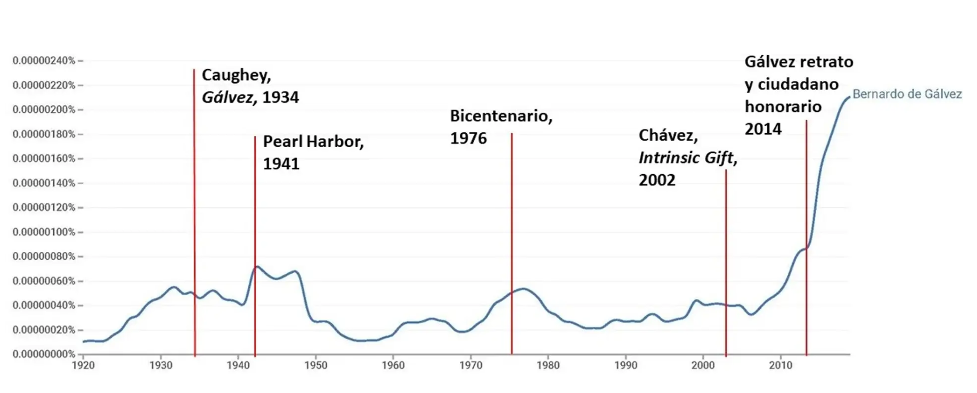

The twentieth century saw a resurgence in the recognition of Spain and Gálvez, though at first very slowly. John Caughey’s 1934 book Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana was the first English-language biography, and Gálvez’s name became even more prominent in military histories written during World War II. The American bicentennial of 1776, during which an equestrian statue of Gálvez was dedicated in Washington, DC by King Juan Carlos I, saw a small bump in recognition.

But it was not until the twenty-first century that Spain and Gálvez began to receive their due. The publication of Thomas Chávez’s magisterial Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift in 2002, followed by the unflagging efforts of Teresa Valcarce and others in 2014 to unveil a portrait of Gálvez, along with a parallel effort to accord him honorary US citizenship the same year, as well as the recent biography Bernardo de Gálvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution by Gonzalo M. Quintero Saravia, all have resulted in a sudden surge of recognition for Spain’s crucial role at the birth of the United States. The efforts of the Spanish Embassy, Queen Sofia Spanish Institute, the Society of the Cincinnati, and many others continue to drive this long-overdue acknowledgement of the shared histories of the two nations.

Dr. Larrie D. Ferreiro, author of Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It, presented these graphs as part of his talk at Anderson House on April 18, 2023, where he explained the evolution of recognition of the Spanish contribution to the Independence of the United States.

Español

“Lafayette” y “Gálvez” son en realidad sustitutos del reconocimiento de (respectivamente) Francia y España en la Guerra de la Independencia Americana, ya que ambos hombres son con diferencia las figuras más emblemáticas de sus respectivas naciones.

El gráfico muestra que durante la guerra, Lafayette (y por tanto Francia) fue más reconocido que Gálvez (y España); no es de extrañar, ya que Francia luchó codo con codo con los estadounidenses, mientras que España estaba ocupada en localizaciones más lejanas.

Lo más interesante es que después de que el Tratado de París de 1783 pusiera fin a la guerra y durante más de cuarenta años (hasta 1824), los nombres tanto de Lafayette como de Gálvez reciben aproximadamente el mismo reconocimiento por la Revolución Americana. El incremento de menciones de Lafayette durante la Revolución Francesa refleja sobre todo su papel en la Asamblea Nacional, en el exilio y como autor de la Declaración de los Derechos del Hombre.

En otras palabras, durante un largo periodo de tiempo tras la Guerra de la Independencia, las historias de la guerra reconocieron tanto a Francia como a España como participantes junto a Estados Unidos.

El reconocimiento de Lafayette (y por tanto de Francia) se eleva significativamente con su gira por América de 1824-1825, que cimentó su reputación de “héroe de dos mundos”, y se consagró con su muerte en 1834. La historia de los Estados Unidos de George Bancroft (1866), reconocida como el conjunto de libros de historia más influyente durante cien años, glorificó aún más el papel de Lafayette.

Sin embargo, Bancroft era un cruzado desvergonzado del Destino Manifiesto, es decir, la creencia de que América debía extender su dominio a través del hemisferio, y el legado español era claramente un anatema para aquello. Su Historia depreció y desestimó el papel español en la independencia de Estados Unidos. Siguiendo el ejemplo de Bancroft, tanto Gálvez como España desaparecieron de las historias americanas de la Revolución durante más de un siglo.

En el siglo XX resurgió el reconocimiento de España y de Gálvez, aunque al principio muy lentamente. El libro de John Caughey Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana (1934) fue la primera biografía en lengua inglesa, y el nombre de Gálvez se hizo aún más prominente en las historias militares escritas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El bicentenario americano de 1776, durante el cual el Rey Juan Carlos I dedicó una estatua ecuestre de Gálvez en Washington, DC, supuso un pequeño repunte en el reconocimiento.

Pero no fue hasta el siglo XXI cuando España y Gálvez empezaron a recibir su merecido. La publicación de la obra magistral de Tomás Chávez España y la Independencia de Estados Unidos: An Intrinsic Gift de Thomas Chávez en 2002, seguida de los incansables esfuerzos de Teresa Valcarce y otros en 2014 para descubrir un retrato de Gálvez, junto con un esfuerzo paralelo para concederle la ciudadanía estadounidense honoraria ese mismo año, así como la reciente biografía Bernardo de Gálvez: Héroe español de la Revolución Americana, de Gonzalo M. Quintero Saravia, han dado lugar a un repentino reconocimiento del papel crucial de España en el nacimiento de Estados Unidos. Los esfuerzos de la Embajada de España, el Queen Sofia Spanish Institute, la Society of the Cincinnati y muchos otros siguen impulsando este reconocimiento, largamente esperado, de las historias compartidas por ambas naciones.

El Dr. Larrie D. Ferreiro, autor de Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It, presentó estos gráficos como parte de su conferencia en Anderson House el 18 de abril de 2023 donde explicó la evolución del reconocimiento de la contribución española a la Independencia de los Estados Unidos.