With All Due Respect: Understanding Anti-Suffrage Women

by Susan Goodier

Although it may be hard to believe today, not everyone wanted women to have the right to vote. In fact, during the early nineteenth century, very few people thought women capable of political engagement of any kind. As the century progressed the women’s suffrage movement steadily increased its membership. By the 1890s, in response to the growing attention suffragists garnered, some women established organizations with the goal of preventing themselves from gaining the right to vote. They had many reasons for doing this, and their arguments changed over time. Perhaps their greatest fear about getting the right to vote was losing what they believed to be women’s power to contribute to the natural function of the nation.

Although it may be hard to believe today, not everyone wanted women to have the right to vote. In fact, during the early nineteenth century, very few people thought women capable of political engagement of any kind. As the century progressed the women’s suffrage movement steadily increased its membership. By the 1890s, in response to the growing attention suffragists garnered, some women established organizations with the goal of preventing themselves from gaining the right to vote. They had many reasons for doing this, and their arguments changed over time. Perhaps their greatest fear about getting the right to vote was losing what they believed to be women’s power to contribute to the natural function of the nation.

Most observers who paid any attention at all to the early women’s rights activists—such as those who organized the convention at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 to demand expanded rights for women in the law, in public, and in the church—found the idea of women being equal to men to be laughable. Most nineteenth-century Americans believed that women belonged in the home to care for husbands and children and to offer their families the serenity of a well-run household. Women’s rights activists held conventions in New York, Ohio, Massachusetts, and elsewhere to expound on views of equality before increasingly large audiences. In the same era, women who joined the anti-slavery movement found many similarities between the oppression of enslaved people and the oppression of women.

The Civil War provided opportunities for many enlightened women. Social justice activists in the North set aside their goals for women’s rights to support the Union’s war effort and encourage the abolition of slavery. They held fundraising fairs, kept farms and businesses running while their male family members fought in the army, and served as nurses on the front lines. When the war ended in 1865, women fully expected to be rewarded with expanded rights, including the right to vote. To the distress of women’s rights leaders, the Reconstruction Amendments added the word “male” to the definition of a citizen in the US Constitution. Linking citizenship with military service, which excluded women, reinforced their exclusion from voting rights. Deeply angered and disappointed, suffragists severed ties with many former abolitionists and formed two new organizations with women’s suffrage as the primary goal. The National Woman Suffrage Association, founded in May 1869, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, founded in September 1869, both worked to achieve women’s right to vote. The National, headed by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York State, worked for a federal amendment to the Constitution, while the American, headed by Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell of Boston, Massachusetts, took a state-by-state approach. The two organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1890.

Soon after, suffragists observed that New York State would be holding a constitutional convention in 1894. One topic under consideration would be whether to eliminate the word “male” from the state’s constitution. The state had added the word in 1867, following suit with the federal constitution. Suffragists converged on the state, well aware that if women won the right to full political equality in New York, other states would follow. Susan B. Anthony and dozens of suffragists canvassed the state, holding meetings and giving speeches in nearly every county. At one meeting, someone in the audience asked Anthony if women wanted the right to vote. She answered that they did not oppose it. Alarmed, a few women realized that if they didn’t do something quickly, there was a good chance they would be forced to vote. These women, many of whom had married lawyers and judges, began meeting in parlors and posh hotels to strategize ways to distance themselves from political responsibilities.

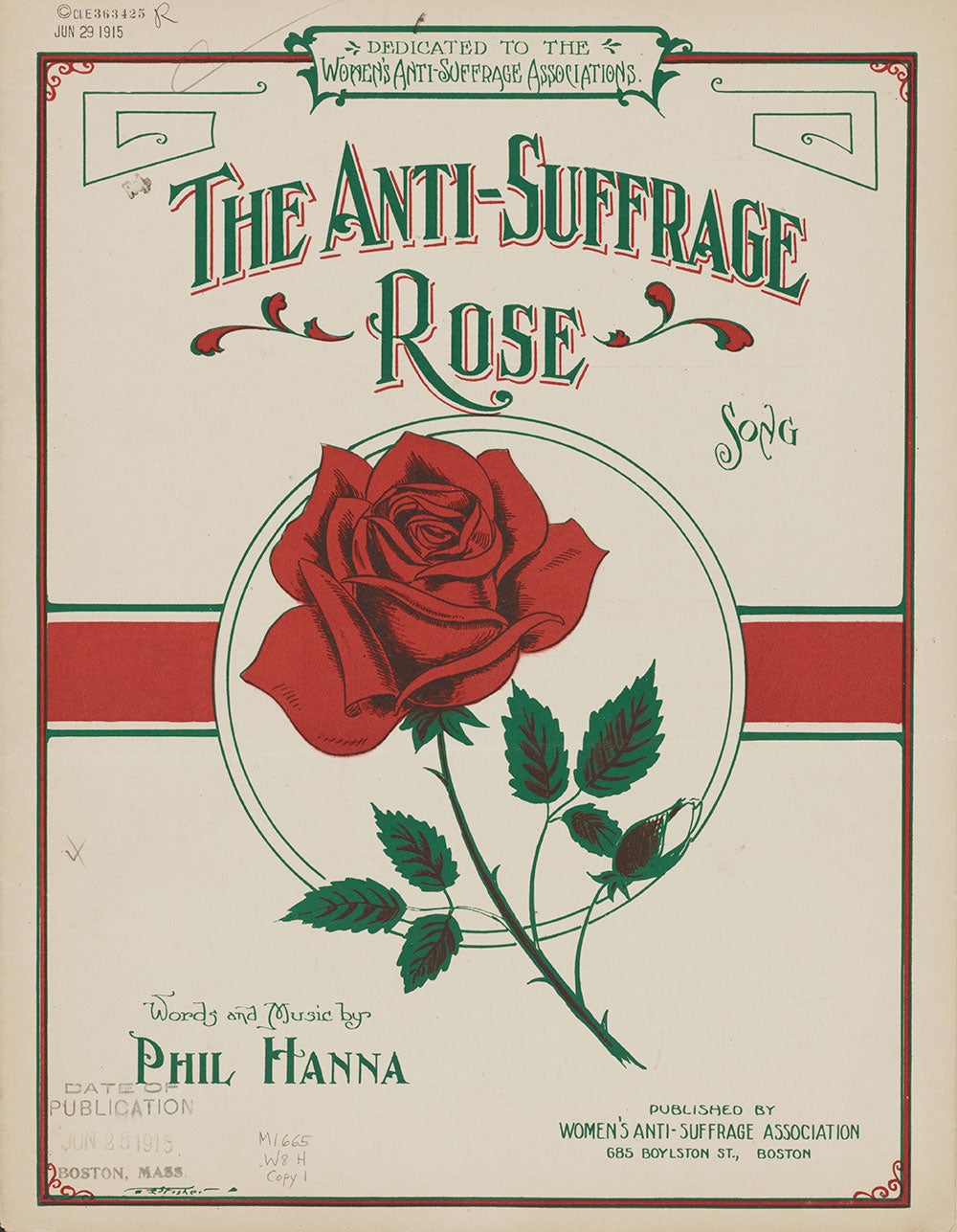

They called themselves “remonstrants,” or anti-suffragists, and set about gathering signatures on petitions to submit to the constitutional convention. Their reasons included the points that most women did not want the burden of the vote, that women were already very busy with homes and families, that suffrage would add to women’s duties in adverse ways, that women’s suffrage would add an unwelcome element to an already encumbered government, and that many women were not capable of making astute political decisions. The delegates to the New York State constitutional convention allowed anti-suffragists as well as suffragists to present their petitions and to speak to legislators. In the end, delegates decided not to put the question before the voters in a referendum. The word “male” remained in the New York State Constitution. Anti-suffragists breathed a sigh of relief.

They called themselves “remonstrants,” or anti-suffragists, and set about gathering signatures on petitions to submit to the constitutional convention. Their reasons included the points that most women did not want the burden of the vote, that women were already very busy with homes and families, that suffrage would add to women’s duties in adverse ways, that women’s suffrage would add an unwelcome element to an already encumbered government, and that many women were not capable of making astute political decisions. The delegates to the New York State constitutional convention allowed anti-suffragists as well as suffragists to present their petitions and to speak to legislators. In the end, delegates decided not to put the question before the voters in a referendum. The word “male” remained in the New York State Constitution. Anti-suffragists breathed a sigh of relief.

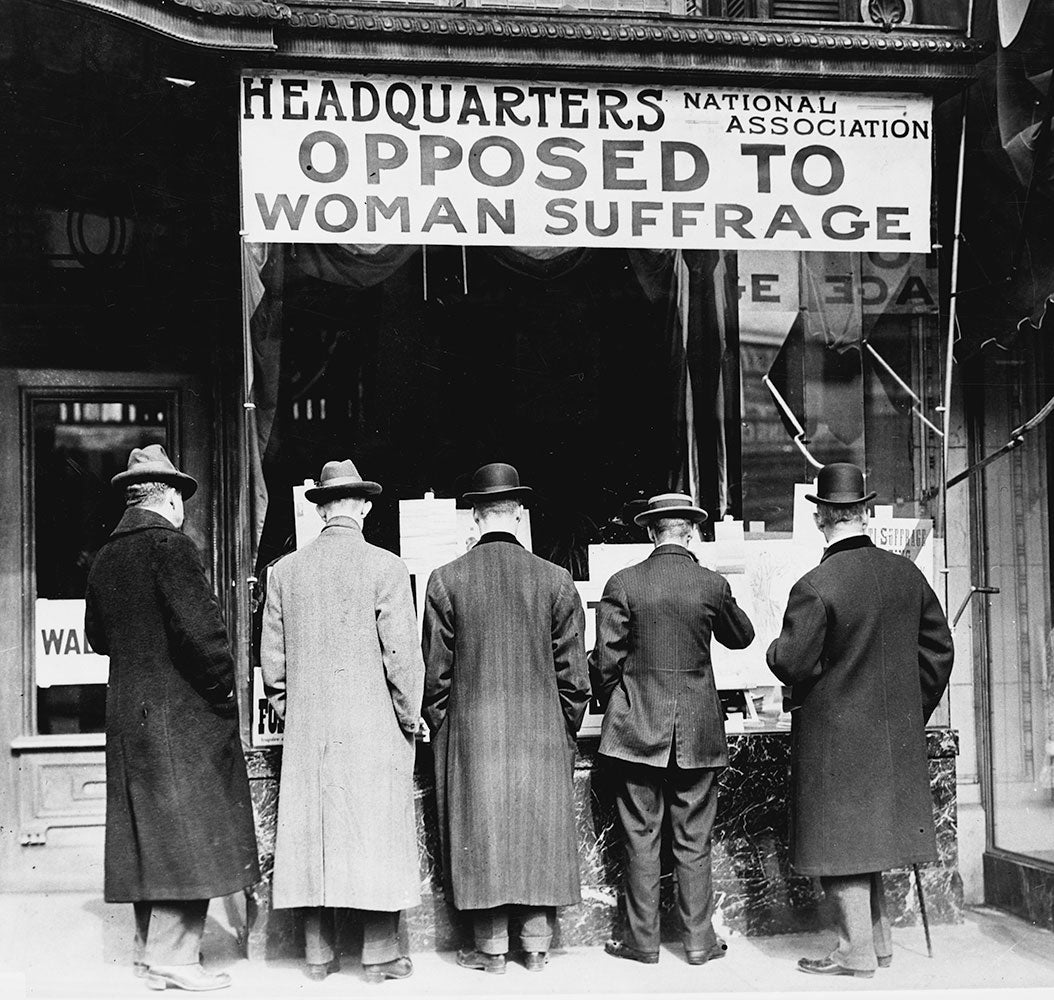

However, the issue refused to die down. Suffragists, inspired by the discussion at the legislative level, turned their attention to educating the public about the need for women to have equal political rights. Horrified by that same discussion, anti-suffragists realized they had to establish their own organization to fight against voting rights, and founded the women-dominated New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Men had more influence in the anti-suffrage organization founded about the same time in Massachusetts. Anti-suffragists met in their homes to educate each other about civic engagement that did not include the right to vote. Anti-suffrage rhetoric became important to suffragists by the first decade of the twentieth century; suffragists found fodder for their own arguments in those anti-suffragists presented. The public found some of the confrontations between antis (as they were sometimes called) and suffragists highly amusing and newsworthy. Americans debated the arguments of suffrage or anti-suffrage on street corners, in shops, in restaurants, and everywhere people gathered.

This give-and-take, back-and-forth argument over women’s place in the polity continued until 1914, the year that the Great War began in Europe. Anti-suffragists believed that women had a duty to support their government, and many recognized that the United States would eventually have to enter the war. Most anti-suffragists believed it was wrong to argue about women’s voting rights in a time of war, and they pressured suffragists to put aside the campaign until the war ended. Suffragists, too, observed the war, but by that time their movement could handle more than one point of view. Some suffragists supported war preparedness, and later, when the United States entered the war in April 1917, sold Liberty Bonds and otherwise bolstered the war effort. Others argued that women should ignore the war because the US government made decisions that impacted women but disregarded their political rights. The most extreme of this group included members of the National Woman’s Party, who picketed the White House from 1917 to 1918. Picketers highlighted the incongruity of a country fighting for democracy while it kept half of the citizenry disenfranchised. Still another suffrage faction, led by Crystal Eastman and Jane Addams, founded the Women’s Peace Party and opposed war on principle. Anti-suffragists criticized pacifists as inimical to patriotism. Almost to a woman, antis supported war preparedness, and later the Red Cross and the war effort itself.

Both the suffrage and anti-suffrage movements changed dramatically during the war years. As people generally became more accepting of women’s public presence and contributions, the opposition weakened. Astute suffragists linked their fight for voting rights to the war effort and found new ways to promote their demands more broadly. Antis became increasingly shrill and desperate, aware that their movement was losing ground. Then, in the fall of 1917, New York State held a referendum, and women won the right to vote in what was then the most heavily populated state. The attention of all suffragists turned to the push for a federal amendment to the US Constitution. Antis, now headquartered in Washington DC, also turned their attention to Congress. They continued the fight against enfranchisement to the bitter end. After women won the right to vote throughout the United States in 1920, antis began to function as a congressional watchdog organization, not disbanding until the early 1930s. By then, many former anti-suffragists had acquiesced to their new political duties and had joined the League of Women Voters and other organizations focusing on educating women about politics and voting rights.

Susan Goodier is a lecturer in history at SUNY Oneonta, recipient of a 2018 Gilder Lehrman Scholarly Fellowship, author of No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement (University of Illinois Press, 2013), and co-author, with Karen Pastorello, of Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2017).