African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment

by Sharon Harley

Sharon Harley is Associate Professor and former Chair of the African American Studies Department at the University of Maryland, College Park. She and historian Rosalyn Terborg-Penn co-edited the pioneer anthology The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images (1978), to which they contributed essays about Black women suffragists. Harley recently published “African American Women and the Right to Vote” in Women and Suffrage (2018) and “‘I Don’t Pay Those Borders No Mind At All’: Audley E. Moore (‘Queen Mother’ Moore)—Grassroots Global Traveler and Activist” in Women and Migration: Responses in Art and History (2018).

At the 1848 women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, traditionally designated as the official launch of the women’s suffrage movement in the US, the nation’s leading black male abolitionist joined prominent white women’s-rights advocates in publicly proclaiming support for the Declaration of Sentiments, including women’s right to vote. At the convention, Frederick Douglass courageously endorsed Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s resolution that it is the “duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.” Two months later, in September 1848, Douglass and other black “freemen” (lawyers, barbers, and ministers) assembled for a three-day national Colored Men’s Convention in Cleveland, Ohio. With the same feminist commitment, Douglass, the newly elected president of the group, proposed a resolution approved by a majority of the delegates, that a woman, a Mrs. Sanford, would be permitted to speak. (In the conference proceedings, she was commended for her “eloquent remarks.”) Douglass subsequently proposed the use of the word “person” to signify all delegates. This resolution’s passage was followed by “three cheers for woman’s rights” and the commitment to “invite females hereafter to take part in our deliberations.” The year 1848 also was significant in that it marked the beginning of the interracial woman’s suffrage movement. To this point, the movement had been dominated by white women who often excluded black women from participating and underplayed the importance of the fight for racial equality.[1]

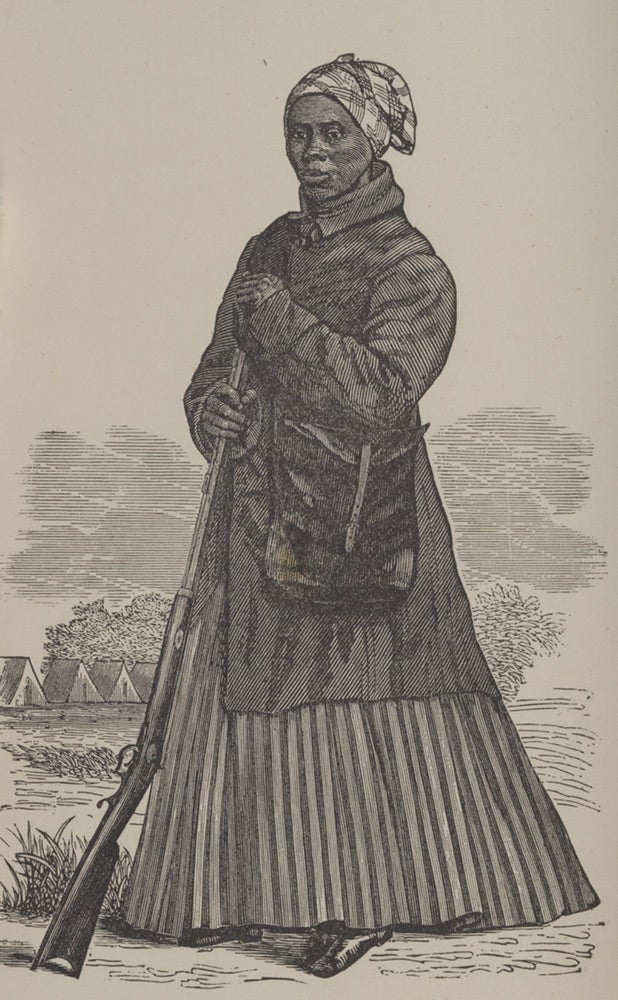

Beginning in the antebellum period, a small cohort of formerly enslaved women, including Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, fought for women’s rights and suffrage. In addition, leading free black women abolitionists and suffragists Margaretta Forten, Harriet Forten Purvis, Henrietta Purvis, Sarah Parker Remond, Maria W. Stewart, and others managed throughout the 1850s and 1860s to attend, organize, speak and assume leadership positions at multiple women’s rights and woman’s suffrage gatherings, as well as to participate in separate black women’s groups and black men’s political gatherings. Generating considerable opposition to both her presence and her woman’s suffrage speech at the 1851 women’s rights meeting in Akron, Ohio, Truth went so far as to bear her breast in response to outrageous claims that she was not a woman. On the other hand, Sarah and her brother Charles Remond won wide acclaim for their pro-women’s suffrage speeches at the 1858 National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City. Location, social status, and the year mattered.

Beginning in the antebellum period, a small cohort of formerly enslaved women, including Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, fought for women’s rights and suffrage. In addition, leading free black women abolitionists and suffragists Margaretta Forten, Harriet Forten Purvis, Henrietta Purvis, Sarah Parker Remond, Maria W. Stewart, and others managed throughout the 1850s and 1860s to attend, organize, speak and assume leadership positions at multiple women’s rights and woman’s suffrage gatherings, as well as to participate in separate black women’s groups and black men’s political gatherings. Generating considerable opposition to both her presence and her woman’s suffrage speech at the 1851 women’s rights meeting in Akron, Ohio, Truth went so far as to bear her breast in response to outrageous claims that she was not a woman. On the other hand, Sarah and her brother Charles Remond won wide acclaim for their pro-women’s suffrage speeches at the 1858 National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City. Location, social status, and the year mattered.

Throughout the Reconstruction decades of the 1860s and 1870s, it was undeniable that for many black women, suffrage was linked to other pressing matters—lynching, sexual abuse, labor, and even criminal justice. Despite the level and enthusiasm of black women’s political involvement and occasional leadership in interracial suffrage organizations, the full story of black women’s suffrage activism has been insufficiently told. We might know, for instance, that Margaretta Forten and Harriet Forten Purvis helped to establish the Philadelphia Suffrage Association. In 1866, they and other black women became active members of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), an organization that endorsed women’s and black men’s right to vote. Harriet Forten Purvis served on the AERA executive committee, and Sarah Remond traveled the East Coast promoting universal suffrage. In a speech delivered at the 1873 AWSA convention, the prominent black suffragist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper articulated a view that was widely held among African Americans, that “as much as white women need the ballot, colored women need it more.”[2]

In 1869, Louisa Rollin courageously proclaimed her support for universal suffrage on the floor of the South Carolina House of Representatives. She and her sisters Frances and Lottie figured prominently in Reconstruction politics and women’s suffrage campaigns at the local and national levels. In 1870, Lottie Rollin was elected secretary of the South Carolina Woman’s Rights Association, an affiliate of the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Despite the hopeful potential of 1848 and the forming of interracial organizations, fights escalated over time and became heated between white women suffragists—especially Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton—and Frederick Douglass and black women suffragists, particularly regarding the Fifteenth Amendment giving black men the right to vote. It was Anthony who asked her “friend” and veteran feminist supporter Frederick Douglass not to attend the 1895 National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in Atlanta, Georgia. Anthony later explained to Ida B. Wells-Barnett that Douglass’s presence on the stage with the honored guests would have offended the southern hosts.[3] Anthony’s and Stanton’s longstanding racist remarks evoked intense anger on the part of some black women suffragists, prompting activist reformers like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to support the Fifteenth Amendment.

As individual white suffragists publicly denounced black male suffrage, it and the larger issue of racial equality remained important components of black women’s suffrage goals. Black women’s recognition of the crucial link between racial equality and women’s rights was evidenced by the number of black women who campaigned, registered, and voted in local school board elections in Chicago, Boston, and elsewhere before and after the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 and the Nineteenth Amendment fifty years later.[4]

While black men were generally in favor of black women’s right to vote, their support was neither uniform nor uncomplicated. Most black men regarded leadership positions in their familial and community settings as for males, even as they acknowledged black women’s key role in confronting racial oppression. To that point, however, noted suffragist and women’s rights leader Mary Church Terrell declared, “For an intelligent colored man to oppose woman suffrage is the most preposterous and ridiculous thing in the world.”[5]

Linking suffrage to a multitude of political and economic issues, Mary Ann Shadd Cary—newspaper editor and first female law school student at Howard University—unsuccessfully attempted to vote in Washington, DC in 1871. This failure notwithstanding, she and a like-minded group of other activist black women insisted upon and secured an officially signed affidavit recognizing that they had attempted to vote. In 1876, Cary wrote to leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association urging them to place black women’s names on their document honoring the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.[6] While unsuccessful in that effort, Cary spoke at the 1878 meeting of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Two years later, she formed the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise Association in Washington, DC, linking suffrage not just to political rights but to education and labor issues.

In 1896, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) provided a prominent platform to promote women’s suffrage and black women’s rights and equality. Suffrage was at the top of the agenda for Mary Church Terrell, the NACW’s first president. Pro-suffrage sentiments appeared in the white and black press, including, in 1894, the Woman’s Era, the first newspaper published by an African American woman, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. In 1913, Ida B. Wells-Barnett organized the Chicago-based Alpha Suffrage Club.

In 1896, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) provided a prominent platform to promote women’s suffrage and black women’s rights and equality. Suffrage was at the top of the agenda for Mary Church Terrell, the NACW’s first president. Pro-suffrage sentiments appeared in the white and black press, including, in 1894, the Woman’s Era, the first newspaper published by an African American woman, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. In 1913, Ida B. Wells-Barnett organized the Chicago-based Alpha Suffrage Club.

Prominent black thinkers and activists offered various opinions on the subject of “Votes for Women” in a special August 1915 issue of the Crisis magazine, the national organ of the NAACP. Black feminist leader and educator  Nannie Helen Burroughs gave a cryptic but profound response to a white woman who asked what black women would do with the ballot: “What can she do without it?” As Burroughs and some others asserted, the black woman of exceptional moral character “needs the ballot to reckon with men who place no value upon her virtue, and to mould healthy public sentiment in favor of her own protection.”[7] In addition to her pro-woman suffrage writings in the Crisis, Burroughs focused her suffrage campaigns in black religious circles, promoting woman suffrage within the black Woman’s Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention.

Nannie Helen Burroughs gave a cryptic but profound response to a white woman who asked what black women would do with the ballot: “What can she do without it?” As Burroughs and some others asserted, the black woman of exceptional moral character “needs the ballot to reckon with men who place no value upon her virtue, and to mould healthy public sentiment in favor of her own protection.”[7] In addition to her pro-woman suffrage writings in the Crisis, Burroughs focused her suffrage campaigns in black religious circles, promoting woman suffrage within the black Woman’s Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention.

Adella Hunt Logan, a life member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and prominent suffragist in the Tuskegee Woman’s Club, wrote in a 1912 issue of the Crisis that African American women were “awake to reforms that may be hastened by good legislation and wise administration, but where she has the ballot she is reported as using it for the uplift of society and for the advancement of the State.” Like other black suffragists, Logan maintained that “women who see that they need the vote see also that the vote needs them.”[8] She stressed that the racial dimension must not be ignored: “If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot . . . how much more do black Americans, male and female, need the strong defense of a vote to help secure their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?”[9]

Black women—a few running for office themselves—actively supported male and female political candidates and led anti-lynching and Republican Party political campaigns, mobilizing black voters. Black voters beyond a doubt contributed to the election of Oscar De Priest in 1915 as the first black alderman in Chicago and in 1928 as the first black US congressman since the Reconstruction era.[10]

One hundred years after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, current Democratic candidates hoping to be the next president of the United States rely heavily on black women voters in South Carolina and elsewhere to ensure their place on the Democratic ticket and their 2020 presidential victory. Following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, the battle for the vote ended for white women. For black women things were more complex.[11] Their political role expanded, and the long arc of their political activism extended through the decades up to the present day.

[1] Report of the Proceedings of the Colored National Convention, Held at Cleveland, Ohio, on Wednesday, September 6, 1848 (Rochester, 1848), pp. 11, 12, and 17. Historian Rosalyn Terborg-Penn remains the leading pioneer scholar in the study of African American women and the vote. See her African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850−1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998). See also African American Women and the Vote, 1837−1965, edited by Ann D. Gordon, Bettye Collier-Thomas, et al. (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997).

[2] Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, closing speech at the 1873 convention of the American Woman Suffrage Association in New York City, as quoted in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 2 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1882), p. 833.

[3] Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Amendment, 1890−1920 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965; repr. Norton, 1981). White supremacist thinking was used to convince white southerners to support the woman suffrage amendment. The former abolitionist Henry B. Blackwell wrote in his 1867 pamphlet, What the South Can Do, that “four millions of Southern white women will counterbalance your four millions of negro men and women, and thus the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged.” As Kraditor observes, this would become the most powerful argument in the South for women’s suffrage.

[4] The work of historian Elsa Barkley Brown helped to redefine black women’s Reconstruction-era political activity and black women’s sense of shared political engagement with black male leaders and voters; see her essay, “To Catch the Vision of Freedom: Reconstructing Southern Black Women’s Political History, 1865−1880,” in African American Women and the Vote, 1837−1965, ed. Gordon, Collier-Thomas, et al, pp. 66−99. For a comprehensive look at black women’s political activism in the late nineteenth century and opening decades of the twentieth century, see Lisa G. Materson, For the Freedom of Her Race: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877−1932 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

[5] Mary Church Terrell, “The Justice of Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis 4, no. 5 (September 1912): 243. See also Paula Giddings, When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (New York: William Morrow, 1984), p. 120.

[6] Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, p. 41.

[7] Nannie H. Burroughs, “Black Women and Reform,” The Crisis 10, no. 4 (August 1915): 187.

[8] Adella Hunt Logan, “Colored Women as Voters,” The Crisis 4, no. 5 (September 1912): 243.

[9] Adella Hunt Logan, “Woman Suffrage,” Colored American Magazine 9 (September 1905): 489.

[10] See Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, ed. Alfreda M. Duster (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1970), pp. 345−347.

[11] See, for instance, Mary Church Terrell, “An Appeal to Colored Women to Vote and Do Their Duty in Politics,” National Notes (November 1925), cited in Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, “Clubwomen and Electoral Politics in the 1920s,” in African American Women and the Vote, ed. Gordon and Collier-Thomas, et al., pp. 134–155.