Why They Marched: Rank and File Perspectives on the Women’s Suffrage Movement

by Susan Ware

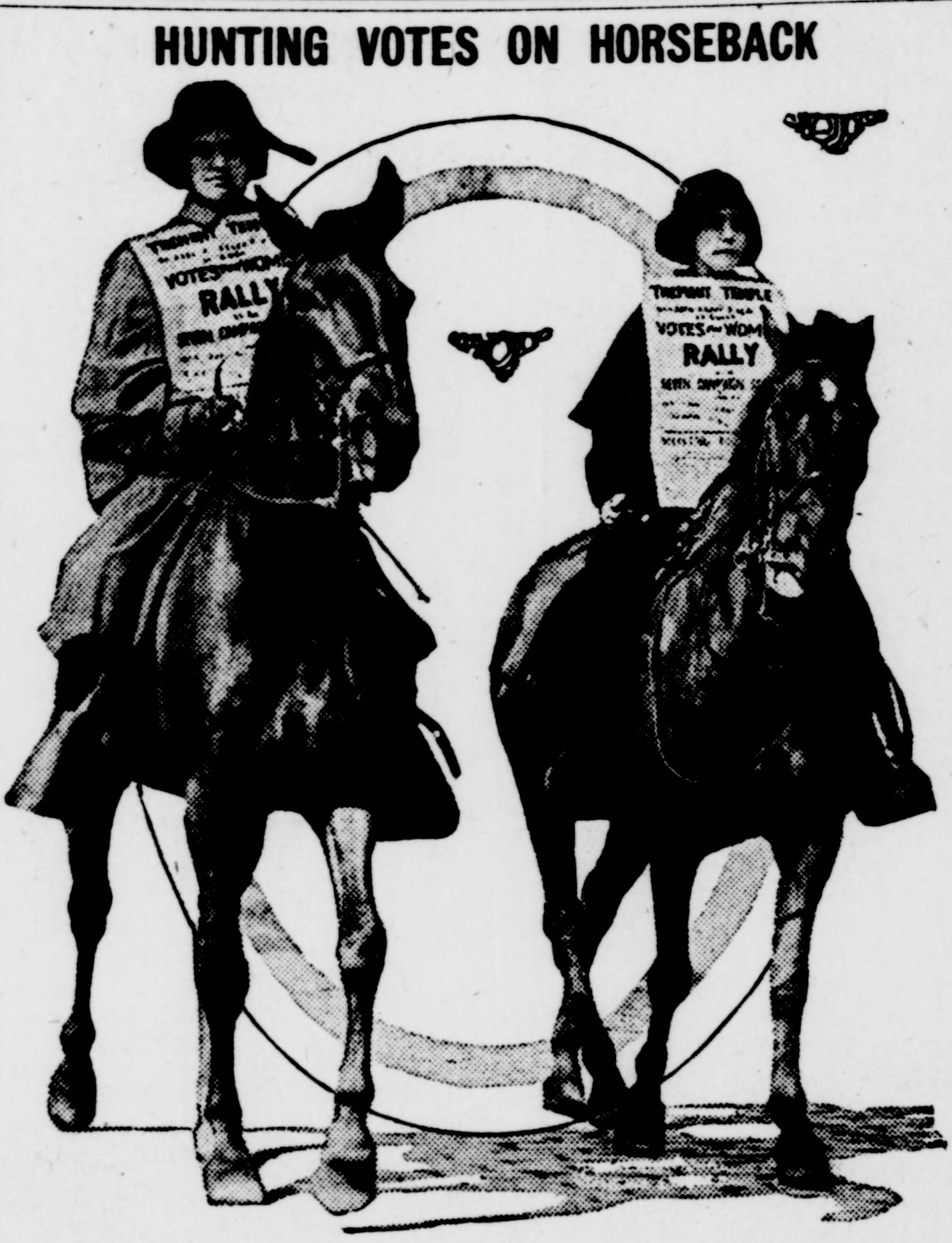

In 1914, a Massachusetts woman named Claiborne Catlin decided to ride across the state on horseback to rally support for women’s suffrage. All of her personal belongings, including a khaki jacket and divided skirt donated by Filene’s department store plus a parcel of leaflets, a horse blanket, and a white, green, and gold “Votes for Women” sash, had to fit in a pair of brown canvas saddlebags. Relying entirely on donations along the way to cover her expenses, she organized fifty-nine meetings, visited thirty-seven cities and towns, and covered 530 miles over the course of four months. As a single woman traveling alone by day and at night, she faced many challenges, including bad weather, lame horses, and even what we would now call a #MeToo moment when a drunken man threatened her physically. She never doubted her mission, calling it “worth every speck of tiredness, every minute of loneliness, every throb of fright.”[1]

In 1914, a Massachusetts woman named Claiborne Catlin decided to ride across the state on horseback to rally support for women’s suffrage. All of her personal belongings, including a khaki jacket and divided skirt donated by Filene’s department store plus a parcel of leaflets, a horse blanket, and a white, green, and gold “Votes for Women” sash, had to fit in a pair of brown canvas saddlebags. Relying entirely on donations along the way to cover her expenses, she organized fifty-nine meetings, visited thirty-seven cities and towns, and covered 530 miles over the course of four months. As a single woman traveling alone by day and at night, she faced many challenges, including bad weather, lame horses, and even what we would now call a #MeToo moment when a drunken man threatened her physically. She never doubted her mission, calling it “worth every speck of tiredness, every minute of loneliness, every throb of fright.”[1]

Claiborne Catlin is an example of an ordinary woman who was driven to do extraordinary things in support of the suffrage cause. While much of the history of women’s suffrage has focused on national leaders and the organizations they founded, there is a much broader and more diverse story waiting to be told by highlighting the women—and occasionally men—who made women’s suffrage happen through actions large and small, courageous and quirky, in states and communities across the country.

Suffragists participated in one of the largest mass mobilizations of women the United States has ever seen, and being part of that collective effort was immensely rewarding for them. Even though many of these women were foot soldiers—after all, not everyone aspired to be a leader like Carrie Chapman Catt or Alice Paul—their rank-and-file contributions made a difference to the larger movement, to the larger society, and to the participants themselves. “It was a continuous, seemingly endless, chain of activity,” Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler realized. “Young suffragists who helped forge the last links of that chain were not born when it began. Old suffragists who forged the first links were dead when it ended.”[2] Focusing on individual suffrage stories puts human faces on the collective drama of broader social change and makes the history come alive.

This emphasis on rank-and-file suffragists is especially important in reclaiming the contributions of African American women, precisely because they were not welcomed into the upper echelons of national suffrage leadership and thus often conducted their activism separately. Some of these stories are well known, such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett defiantly joining the Illinois delegation during the 1913 women’s suffrage parade in Washington DC despite being told to march separately with other women of color at the back.  Other stories are waiting to take their rightful places in the broader suffrage narrative: Maria W. Stewart becoming the first American woman, black or white, to speak in public about women’s rights in 1832; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper reminding delegates to the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1866 that “we are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity”[3]; Mary Church Terrell deciding to deliver a speech in German to the International Council of Women in Berlin in 1904 so that delegates could understand what she, the only woman of color in attendance, had to say about the status of African American women in the United States. White suffragists often ignored these messages at the time, but the intersectional vision of African American suffragists speaks powerfully to us today.

Other stories are waiting to take their rightful places in the broader suffrage narrative: Maria W. Stewart becoming the first American woman, black or white, to speak in public about women’s rights in 1832; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper reminding delegates to the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1866 that “we are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity”[3]; Mary Church Terrell deciding to deliver a speech in German to the International Council of Women in Berlin in 1904 so that delegates could understand what she, the only woman of color in attendance, had to say about the status of African American women in the United States. White suffragists often ignored these messages at the time, but the intersectional vision of African American suffragists speaks powerfully to us today.

Unearthing new suffrage stories is also a way to highlight the regional diversity of the suffrage movement, especially the role of the West. Cora Smith Eaton, a pioneering physician and avid mountaineer who planted a Votes for Women pennant on Mount Rainier in 1909, was an officer of the Washington State suffrage organization. Hazel Hunkins, who joined the National Woman’s Party picket lines outside the White House and was jailed for her suffrage advocacy, spent her first two decades in Montana, the state that made Jeannette Rankin the first woman elected to Congress in 1916. Emmeline Wells, a Mormon from Utah who was in a polygamous marriage, shows how the questions of Mormonism and women’s suffrage intersected in unexpected ways. Further demonstrating regional diversity, the lives of southern suffragists, such as bestselling writer Mary Johnston who wrote a suffrage novel that tanked, noted Mississippi suffragist Nellie Nugent Somerville, who held national leadership positions, and Sue Shelton White, who helped push Tennessee into the ratification column in August 1920, capture the special challenges of pressing for women’s suffrage in a region committed to states’ rights and white supremacy.

Focusing on the lives of lesser-known suffragists also offers a chance to “queer” the suffrage movement. By virtue of declaring their support for the cause in the first place, suffragists took themselves outside the bounds of what was considered acceptable heteronormative behavior for women at the time. In turn the women’s suffrage movement provided a place where it was okay to be different, okay to be an outlier in regard to accepted gender norms. Molly Dewson and Polly Porter, dubbed the “farmer-suffragettes” by their skeptical neighbors, demonstrated how deep friendships could turn into lifelong partnerships. Suffragists like Ray and Gertrude Foster Brown participated in a companionate marriage, with both husband and wife signed on to the cause. “New Women” such as Doris Stevens and Inez Milholland experimented with and claimed sexual prerogatives usually reserved for men. And even national leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt lived decidedly unconventional personal lives. Viewed in this way, suffragists turn out to be a much more interesting bunch than their somewhat dour public reputation gives them credit for.

While women’s suffrage is often seen primarily as a political movement, the suffrage cause was not something that its participants could turn off at the end of the day when the picket signs were put away and the last meeting adjourned. Becoming a suffragist had the potential to change a woman’s relationships with her family of origin and with the significant others in her life, especially husbands and partners, but friends and professional colleagues as well. It might affect her political party identification, her livelihood, which organizations she belonged to, and where she lived and traveled. Participating in suffrage events could even affect how she dressed.

Women were proud to be part of this great crusade, and they cherished the solidarity it engendered for the rest of the lives. Frances Perkins, a veteran suffragist and the first woman to serve in the Cabinet, remembered it this way: “The friendships that were formed among women who were in the suffrage movement have been the most lasting and enduring friendships—solid, substantial, loyal—that I have ever seen anywhere. The women learned to like each other in that suffrage movement.” [4]

In 1920 Oreola Williams Haskell published a book called Banner Bearers: Tales of the Suffrage Campaigns, which told the story of ordinary suffrage workers going about their daily business through a series of fictional sketches “each embodying one special feature of the many-sided efforts to win the vote.” One hundred years later, we have another chance to recreate the passion and commitment that three generations of American women brought to the suffrage cause by telling its history from the perspective of “those who have waged its battles and won its victories.” That means bringing the story down to the personal level—to individual acts of courage and political defiance, to stories of quiet determination alongside displays of public spectacle. “May these pages seem like the diary they have never had time to write,” Haskell hoped, “or like the portfolio of old photographs that, though faded, make the once vivid past live again.” [5] These are the suffrage stories waiting to be told.

[1] “Stirrup Cups,” typescript account by Claiborne Catlin Elliman of her suffrage trip for the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Claiborne Catlin Elliman Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, entry for September 1, 1914, p. 72.

[2] Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1923), pp. 107−108.

[3] Speech of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, in Proceedings of the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention . . . May 10, 1866 (New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1866), pp. 45–48.

[4] Reminiscences of Frances Perkins in the Oral History Collection, Columbia University, printed in Susan Ware, Beyond Suffrage: Women in the New Deal (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), p. 31.

[5] Oreola Williams Haskell, Banner Bearers: Tales of the Suffrage Campaigns (Geneva, NY: W. F. Humphrey, 1920), pp. 5, [3], and 4.

Susan Ware is the Honorary Women’s Suffrage Centennial Historian at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, and the general editor of American National Biography. She is the author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019) and the editor of American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote, 1776–1965 (forthcoming, Library of America, July 2020).