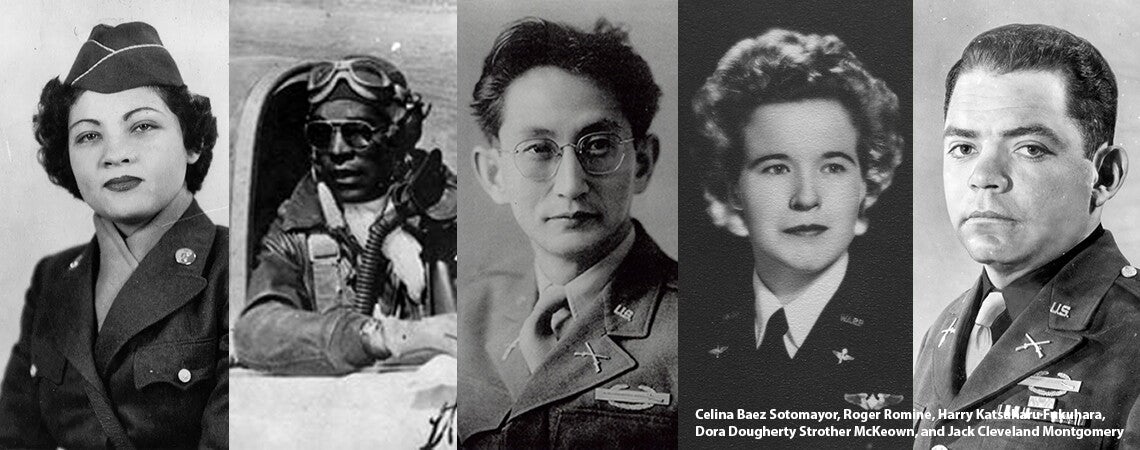

Dora Dougherty Strother McKeown, Women Airforce Service Pilot in World War II

by Katherine Sharp Landdeck

When Dora Dougherty Strother McKeown was just a kid she couldn’t wait for Sunday. For every Sunday her entire family would climb into their old Oakland motor car and drive to the airport to spend the day watching planes fly. It had only been a few decades since the Wright Brothers first flew in 1903, and Dora’s family, along with most Americans, were obsessed with the airplane. Dora’s father had served in the US Army Infantry during World War I and flown as an observer in an open-cockpit bi-plane. He had become fascinated with flight and shared that passion with his family. Dora hoped to fly, and perhaps even serve her country one day, too.

When Dora Dougherty Strother McKeown was just a kid she couldn’t wait for Sunday. For every Sunday her entire family would climb into their old Oakland motor car and drive to the airport to spend the day watching planes fly. It had only been a few decades since the Wright Brothers first flew in 1903, and Dora’s family, along with most Americans, were obsessed with the airplane. Dora’s father had served in the US Army Infantry during World War I and flown as an observer in an open-cockpit bi-plane. He had become fascinated with flight and shared that passion with his family. Dora hoped to fly, and perhaps even serve her country one day, too.

Dora’s mother took education seriously. She was a college graduate with degrees in physics and chemistry, fields that were decidedly “unladylike” at the time. When Dora came home to Chicago from her own college for summer break in 1940, her mother insisted she attend summer school to continue her learning. Northwestern University was offering courses in aviation through the Civilian Pilot Training Program, a government-run program to increase the number of pilots in the United States as World War II raged in Europe. Primarily for men, the CPTP allowed one woman in every class of ten. Dora jumped at the chance and before she went back to school for the fall semester she had her pilot’s license.

In the fall of 1942, the United States was desperate for more pilots. Men were being trained and sent to war in Europe and the Pacific. At the same time, American factories were beginning to build thousands of new planes for those men to fly into combat. Those factories were scattered across the United States, from Detroit to Dallas to Long Beach, California. And all those planes needed to get from those factories to the coasts so they could be put on ships (for the smaller pursuit aircraft) or flown overseas (bigger bombers) to the men who needed them to fight against Germany and Japan. There simply weren’t enough pilots to do all of the flying work that needed to be done.

Two prominent women pilots, Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Love, had been pushing leaders in the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) to utilize women pilots since before the war began. Cochran had even written to Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of President Roosevelt and the most active First Lady in history, imploring her to advocate for women pilots—which Roosevelt did in her “My Day” column many times, including the September 1, 1942, column in which she called women pilots “a weapon waiting to be used.”

Finally, in September 1942, General Henry H. Arnold of the US Army Air Forces agreed to give women pilots a chance, despite being unsure if women would be strong enough to fly military planes. He tapped two women to lead. Nancy Love recruited more experienced women pilots with some 500 hours of flight experience who could go right into working for the Ferrying Division of the Air Transport Command and ferry planes from factories to point of embarkation. Jacqueline Cochran began a massive effort to recruit women pilots with less experience, train them for Army flying, and then once they had the extra experience they needed, send them to Nancy Love to be ferry pilots.

Dora learned about the opportunity for women to fly for the USAAF and told her parents she wanted to quit college to build more flying time and apply. They were hesitant, but when she promised she would return to college once the war was over, they agreed. The requirements were steep, and in addition to flying time (which ranged from 200 down to 35 hours over the life of the trainee program) and the same military flight physical as the men cadets, also included letters attesting to the women’s good moral character and a personal interview. Over 25,000 women applied and only 1,830 were admitted. Dora considered herself lucky to join the third class of women trainees, Class 43-W-3 (43 for 1943, W for women pilots, 3 for the third class) in Houston, Texas, for training.

Training in Houston was tough for the women pilots. They flew out of the main Houston airport and there simply weren’t adequate facilities for them. The weather wasn’t good for flying either. Before Dora had finished training, the USAAF moved the women to Avenger Field, near Sweetwater, Texas, to train. Avenger had been an airfield where British pilots were training, but in early 1943 the men were moved out and it became the first all-women’s pilot training base in the country.

The women trainees followed the same training the men cadets did. They had ground school for half of the day and took classes like math, weather, and military protocol. Dora was particularly good at her class in Morse code, a primary form of communication for pilots at the time (although many of her classmates hated the class). They would listen to the dots and dashes that symbolized letters and write out the words. The other half of the day the women would get to fly. They started with primary trainer planes, such as a Stearman Biplane, then moved into basic trainers like the BT-13, then into advanced trainers like the AT-6 Texan. (For more information about the airplanes the women pilots flew, scroll to links at the end of the essay.) It was hard work learning how to fly these new planes and how to fly them the way the Army wanted them to. Multiple times during their training they would have a flight-check, a kind of test to see if they were approved to move to the next phase of training. Often it would be with a designated instructor (other than their own) but sometimes it would be with an official Army check pilot. Dora had test anxiety. She wanted to succeed so badly that she’d get nervous about things she knew and she failed two of her important check-rides. Luckily, she got a third and final chance and passed. She graduated with class 43-W-3 on July 3, 1943, after over six months of training.

After graduation, Dora thought she would be a ferry pilot, but the Army Air Forces had a new idea. They decided to expand the experiment of women pilots to see what other work the women could do. Dora joined some others in her class and went to Camp Davis, North Carolina where she was trained to tow targets behind an A-24 Douglas Dauntless dive bomber. These targets were towed so that gunners on the ground could learn how to fire at a moving plane using live ammunition. After several months there, Dora moved to Liberty Field, Georgia, where she learned to operate a PQ-8 and PQ-14, new secret radio-controlled aircraft. Two of the women pilots would fly in an AT-17 (UC-78) Bamboo Bomber—one to fly the plane, one to fly the radio-controlled plane ahead of them. Another woman would fly “safety pilot” in the PQ-8 in case there was a mishap so she could land it safely. This was important work, but Dora went on to do something even more special.

The USAAF desperately needed a long-range, high-altitude plane for the long distances of the war in the Pacific. Boeing Aircraft designed and built the big, pressurized, 4-engine B-29 Superfortress for the job. Unfortunately, in the beginning it had problems, particularly with engine fires, and the plane earned a bad reputation among Army pilots who were refusing to fly it. Colonel Paul Tibbets was put in charge of getting the pilots to fly. He met Dora and another Women Airforce Service Pilot (WASP) (the name of the women pilot group), Dorothea Johnson Moorman, and believed them to be good pilots who could help him solve his problem. He knew that women had been used with other planes to prove they were “so easy to fly even a woman could do it” and decided to use some of the men’s bias against them. Tibbets quickly trained the women in flying the B-29, and then they all toured the various bases in the US with the plane and did demonstration flights for the men. Some of the men got mad but others were grateful to learn new techniques flying that particular plane. After just a few weeks the women were forced out of the plane by a senator who worried they were shaming the men too much. But their job was done, men were back flying the plane, and the B-29 became an essential part of the war in the Pacific.

In December 1944 the WASP were disbanded and sent home, even though the war was still ongoing. Enough men pilots had returned from the war and were available to do the domestic flying (the WASP never flew overseas) the women had been doing. The idea was that women could release men for flying duty but couldn’t replace them. Once the men were available, the women were thanked for a good job and sent away. A similar fate awaited the Rosie the Riveters and other women factory workers not long after.

Dora and the other women were very unhappy. They had all this flying experience and wanted to continue to serve their country, but they were no longer wanted as pilots. Some of the women joined the American Red Cross, and a few others worked as air traffic controllers. Dora kept her promise to her parents and soon returned to college to finish her degree. She tried to join the Veterans group on campus. She’d spent two years on military bases, following military protocol, flying military planes, and just felt more comfortable with other Veterans. But she was rejected by the organization. She was a woman and she had technically been a civilian. Although the USAAF always planned to make the women an official part of the Army, and in fact there was a bill before Congress to do so in 1944 that narrowly failed under intense pressure from a group of men pilots to deny the women, they were technically a part of the Civil Service.

When the United States Air Force began as an independent branch in 1947, Dora quickly joined as a part of the Reserves. She was not allowed to fly again because the USAF didn’t need women to fly so they didn’t allow them to, but she was able to continue serving her country. She served nearly thirty years and retired as a lieutenant colonel. Dora continued her education and eventually earned her PhD from New York University in 1955. She soon began working at Bell Helicopter and eventually became chief of human factors engineering and cockpit design. She earned her helicopters license and set two world records in the helicopter while she was at it. Her important work in aviation led President Lyndon B. Johnson to appoint her to the Federal Aviation Administration’s Women’s Adivsory Committee in 1964.

In the 1960s and 1970s the women of the WASP began to realize they, and the thirty-eight women who died while serving, had been forgotten. Dora was among the leaders in the grassroots effort and testified before Congress to get official recognition of the work they’d done during the war, hoping to correct the wrong of them not being considered Veterans. With the support of Senator Barry Goldwater, who had flown with many of the women as a ferry pilot during the war and argued if he was a Veteran they should be too, the WASP were recognized as Veterans in November 1977. They were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in honor of their service in 2009.

After a lifetime of service to her country, Dora Dougherty Strother McKeown died in November 2013 at the age of ninety-one and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Katherine Sharp Landdeck is professor of history and director of Pioneers Oral History Project at Texas Woman’s University. She is the author of The Women with Silver Wings: The Inspiring True Story of the Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II (Crown Publishing, 2020). In 2015, she was a contributing producer and historian on the film Silver Wings, Flying Dreams: The Complete Story of the Women Airforce Service Pilots and in 2020 produced the Emmy Award–winning film WASP: A Wartime Experiment in WOmanpower.

For more on the airplanes flown by the Women Airforce Service Pilots (in order of appearance in the essay):

Stearman Biplane

BT-13

AT-6 Texan

A-24 Douglas Dauntless

PQ-8 and PQ-14

AT-17 (UC-78)

B-29