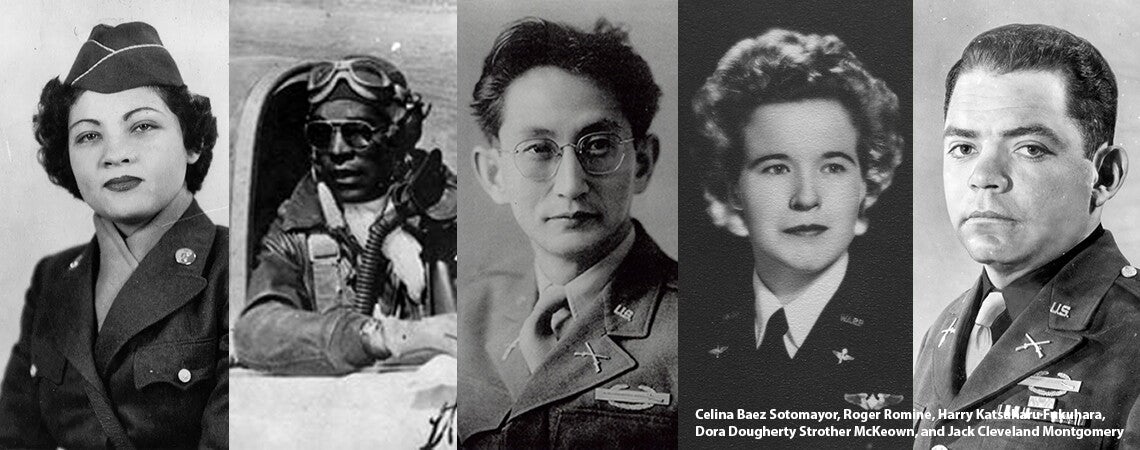

The Life and Death of Roger Romine: A Tuskegee Airman Gone Too Soon

by Lisa Bratton

The Tuskegee Airmen were an elite group of African American pilots and support personnel who fought in World War II. Their relevance in the African American struggle for equality and respect cannot be overstated. During World War II, the United States Army Air Corps was one organization and consisted of both the Army and the Air Force. This branch of the military was completely segregated. In fact, it could be stated that there were two militaries: one African American and one White.

The Tuskegee Airmen were an elite group of African American pilots and support personnel who fought in World War II. Their relevance in the African American struggle for equality and respect cannot be overstated. During World War II, the United States Army Air Corps was one organization and consisted of both the Army and the Air Force. This branch of the military was completely segregated. In fact, it could be stated that there were two militaries: one African American and one White.

Even though African Americans have fought in every war the United States has ever experienced, the Army War College, a group of White, male military officers who advised the president on matters pertaining to war, decided to study how best to utilize African American soldiers in war. In 1925, the War College issued a report entitled “The Use of Negro Manpower in War.” Under Section IV, “Opinion of the War College,” the report states: “the American Negro has not progressed as far as the other sub-species of the human family. As a race he has not developed leadership qualities. . . . In past wars the negro has made a fair laborer, but an inferior technician.” [1] It was in this environment that Roger Romine and other Tuskegee Airmen studied, trained, and sacrificed to serve this nation.

Roger Romine was born on July 30, 1920, to Elmer and Viola Majors Romine in Oakland, California. According to the 1930 US Census, both of his parents were born in the 1890s and were literate. His father worked as a waiter in a dining car. His mother’s occupation is not specified so she was most likely a homemaker. Roger Romine had one brother, Elmer Jr., who was four years older, and one sister, Gloria, who was two years younger. Interestingly, one of Roger Romine’s grandparents was born in England.[2]

Roger Romine was born on July 30, 1920, to Elmer and Viola Majors Romine in Oakland, California. According to the 1930 US Census, both of his parents were born in the 1890s and were literate. His father worked as a waiter in a dining car. His mother’s occupation is not specified so she was most likely a homemaker. Roger Romine had one brother, Elmer Jr., who was four years older, and one sister, Gloria, who was two years younger. Interestingly, one of Roger Romine’s grandparents was born in England.[2]

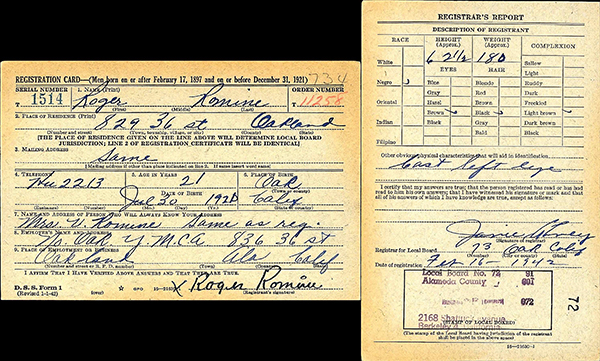

According to the 1940 Census, nineteen-year-old Roger Romine was living with his family while in college. His older brother, Elmer Jr., followed the career path of their father and was working part-time as a waiter in a dining car. Mrs. Viola Romine and seventeen-year-old Gloria were also living in the home. Roger Romine Sr. finished fourth grade, his wife finished eighth grade, and both sons had completed at least one year of college. Roger Romine matriculated at Salinas Junior College (now Hartnell College) and San José State University before he joined the military. The family resided at 829 36th Street in Oakland and Roger worked at the North Oakland YMCA located just across the street at 836 36th Street. At the time of his employment, the YMCA was segregated; it was desegregated in 1944.[3]

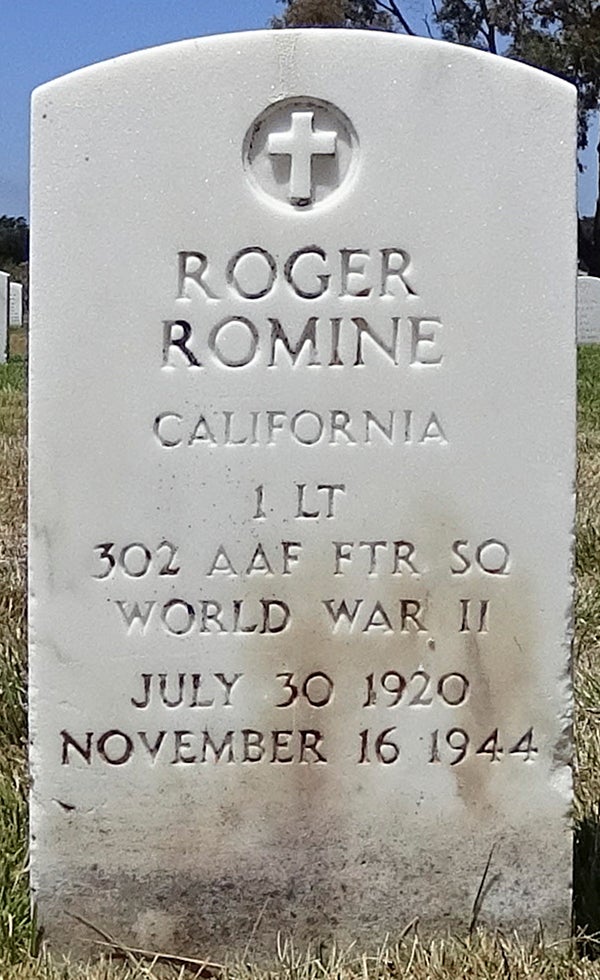

Roger Romine registered for the draft on February 16, 1942. According to his draft card, he was 6′2″, weighed 180 pounds, and had lost his left eye. He trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field and graduated as a 1st lieutenant in Class 43-H-SE on August 30, 1943. An unpublished email dated January 28, 2010, from researcher Dr. Dan Haulman to the author indicated that Romine shot down enemy aircraft in Italy on July 18, July 26, and October 12, 1944.

From the years 2000 to 2005, five historians, including the author, collected over 800 interviews of Tuskegee Airmen for the US National Park Service Oral History Project. Two interviewees, Burl Smith and Woodrow Crockett, provided details on the tragic plane crash that led to Lt. Romine’s untimely death.

From the years 2000 to 2005, five historians, including the author, collected over 800 interviews of Tuskegee Airmen for the US National Park Service Oral History Project. Two interviewees, Burl Smith and Woodrow Crockett, provided details on the tragic plane crash that led to Lt. Romine’s untimely death.

On November 10, 2004, Mr. Burl Smith was interviewed by Judith Brown in Oakland, California. Mr. Smith stated:

A very good friend of mine was killed over there, but he was killed on the runway: Roger Romine. I think he was just twenty-three years old. But his was a freak accident, the way I heard the story. A farmer drove a flock of sheep across a runway and he and his wingman were taking off. The wingman couldn’t see the sheep. Roger saw them, and he tried to abort the mission, and he chopped his throttle; otherwise he was going to hit the sheep. His wingman came up behind him and chewed up the cockpit with the propeller. Killed him.

On March 15, 2001, Lt. Col. Woodrow Crockett was interviewed by William Mansfield in Virginia. Crockett provided an eyewitness account:

One guy got stuck in the mud; then the next guy took off. Didn’t have his goggles down. He did have his gloves on. But he ran through—an Italian papa-san [who] was crossing the runway with a herd of sheep. He ran through the sheep and collided with this other airplane. Lt. Roger Romine was in that airplane.

Here you have two P-51s with 75-gallon drop tanks [full of fuel] with all the ammunition, all the guns. The fire must have been about four feet off the ground.

So the first guy, the leader of the group was Roger Romine. He took off or tried to take off, and at about midway on the runway, the plane wouldn’t take the power, and so he cut back and started applying the brakes. He ended up out in the mud.

So instead of getting out, he stayed in the plane and was trying to gun the plane out of the mud. The second man to take off comes roaring down on the other side. Here’s the second plane coming along, a man named Hill. Just at this time, the sheepherder took this opportunity to drive his sheep across the end of the runway. So the second plane sees these sheep coming across the runway and he’s about to crash into the sheep. He swerves his plane, but in swerving, he hit several of the sheep, and it chopped them up in pieces. That put him right on line with this first plane that was struggling to get out of the mud.

He climbed right up on the back of this plane, and you heard this gasoline: SWOOSH! And flames were up, like, a thousand feet in the air. Romine is trapped in the lower plane. The guy in the top plane, Hill, jumps out of his plane. He’s on fire, and he’s rolling around in the grass, and bystanders are rushing up to him, to put out the fire. But meanwhile, naturally, the man in the first plane is dead because he was trapped.

When we came back [from the mission,] we found that we had only lost that first pilot, Romine. I got a report on how his remains looked; there was nothing but a lump of charcoal. And this guy was a good-looking guy.

Another little adjunct to this: His mother was out in California with my mother. She would meet Mrs. Romine at the market in Berkeley [and] they would talk about their sons. My mother said [Mrs. Romine] was so pitiful after she got the word that her son was dead that she actually—you know, she felt like kind of evading her because it was hard to take her grief.

Lt. Roger Romine died on November 16, 1944, and is buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California.

Lisa Bratton received her PhD in African American Studies from Temple University in Philadelphia. She is currently an associate professor of history at Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Alabama. From 2000 to 2005, she was a historian for the National Park Service Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project and conducted more than 250 oral histories of men and women involved in the experience. Her upcoming book is on resistance at Historic Brattonsvillle, the South Carolina plantation on which her ancestors, Green and Malinda Bratton, were enslaved.

Recommended Reading

Buckley, Gail. American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm. New York: Random House, 2001.

Caver, Joseph, et al., The Tuskegee Airmen: An Illustrated History, 1939–1949. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2011.

Cooper, Charlie and Ann. Tuskegee’s Heroes: Featuring the Aviation Art of Roy LaGrone. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International Publishers, 1996.

Dryden, Charles W. A-Train: Memoirs of a Tuskegee Airman. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

Homan, Lynn, and Thomas Reilly. Black Knights: The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2001, repr. 2018.

Moye, Todd. Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Warren, James C. The Tuskegee Airmen Mutiny at Freeman Field. Vacaville, CA: Conyers Publishing Company, 1995.

[1] Army War College, “Memorandum for the Chief of Staff [on] the Use of Negro Man Power in War,” Washington, DC, October 30, 1925. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/documents/356632/390886/tusk_doc_a.pdf/46931….

[2] The 1920 US Census indicates that his grandfather was from England and his grandmother was from Louisiana. The 1930 Census indicates the opposite: that his grandfather was from Louisiana and his grandmother was from England.

[3] Dorothy Londagin, “The Black Y’s of Oakland,” A Bit of History, 2020, https://abitofhistory.site/2020/09/12/the-black-ys-of-oakland/.