Madeline Traces: Confronting the Marks of History

by Lauret Savoy

This essay is an updated and revised abridgement of the chapter “Madeline Traces” from Lauret E. Savoy’s book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape (Counterpoint Press, 2015, 2021).

Many headwaters rise in the mid-continent. They flow as the terrain suggests, toward the Mississippi River, toward Hudson’s Bay, toward the great lake named Superior. A visitor to the boreal woodlands and lakes of northern Wisconsin and Minnesota might suspect time moves slowly here. But anyone equating gentleness of contour with quietness does so at great peril. Tumultuous histories lie beneath subtle appearances. They have a far reach.

Many headwaters rise in the mid-continent. They flow as the terrain suggests, toward the Mississippi River, toward Hudson’s Bay, toward the great lake named Superior. A visitor to the boreal woodlands and lakes of northern Wisconsin and Minnesota might suspect time moves slowly here. But anyone equating gentleness of contour with quietness does so at great peril. Tumultuous histories lie beneath subtle appearances. They have a far reach.

A friend’s gift of solitude brought me to Lake Superior’s southwestern shore, to Madeline Island, largest of the Apostle Islands. I had never visited this part of Wisconsin, and assumed my ignorance of the region’s history, of its landscapes, meant little if anything connected to me. But as I came to be in this place, came to learn names and stories both born and imposed here, my mistake became clear. Even grade-school wanderings through history, literature, and science began to show a much darker side.

I take many lessons from Madeline Island. One is this: I am both a collector and an arrangement. I might gather stones, collect books, or save mementos. But my own experiences, too, are gathered up and swept along by currents of a still-unfolding history. This northland touched me as a child and knows me still. I suspect it might know you, too.

***

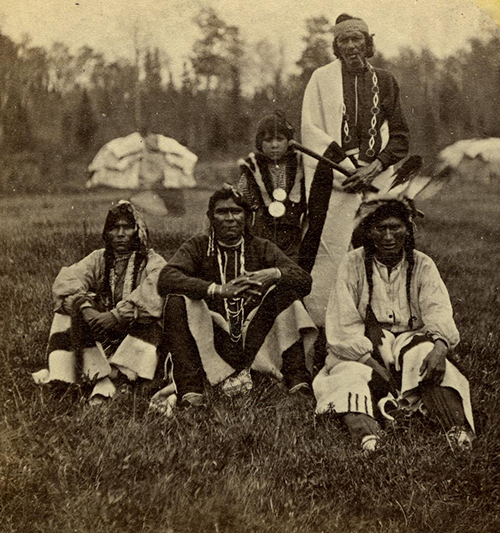

The uppermost and largest of the Great Lakes was long known to the Anishinaabeg as kitchigame, freshwater sea. Gerald Vizenor, an author and a descendant of these original people of the woodland lakes, remembers moningwanekaning (Madeline Island in Anishinaabemowin) as “our tribal home, the place where the earth began.”[1] The Anishinaabeg did not name themselves Ojibwa or Chippewa.[2] “Ojibwa” was applied by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. By one account the word was misheard and recorded into nineteenth-century treaties as “Chippewa.” Vizenor has lamented that his people “must still wear the invented names.”[3]

The uppermost and largest of the Great Lakes was long known to the Anishinaabeg as kitchigame, freshwater sea. Gerald Vizenor, an author and a descendant of these original people of the woodland lakes, remembers moningwanekaning (Madeline Island in Anishinaabemowin) as “our tribal home, the place where the earth began.”[1] The Anishinaabeg did not name themselves Ojibwa or Chippewa.[2] “Ojibwa” was applied by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. By one account the word was misheard and recorded into nineteenth-century treaties as “Chippewa.” Vizenor has lamented that his people “must still wear the invented names.”[3]

The Henry Schoolcraft introduced to me in fifth-grade social studies was the discoverer of the Mississippi River’s source and the leading “Indian scholar” of his day. So enthralled was I by this apparently intrepid explorer that I chose his work and life as the topic of my class report. I learned and recounted “facts” available to me through my basic library skills. Among them:

- As the first American to gather and publish Indian stories in nearly original form, Schoolcraft became the “father” of American folklore and anthropology.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow based his masterpiece The Song of Hiawatha on tales he read in this work.

- Schoolcraft’s reports—the first accounts of minerals around Lake Superior—spurred mining and geologic study, thus aiding our nation’s economic foundation and the growth of scientific knowledge.

As a ten-year-old I didn’t recognize any complexity or contradiction; I simply retrieved, accepted, and repeated printed stories. Not only was I unaware that narratives of the past aren’t simply actual events recounted under the authority of truth, I also adopted a perspective weighted by the heavy baggage of assumptions and attitudes. Of conflicting points of view or contending interests my ignorance was nearly complete. That Schoolcraft’s geographic “discovery” came from his asking Indigenous peoples the location of the river’s source. That as “Indian agent” he helped the federal government claim, through treaty cessions, land around Lake Superior as controlled targets of mining. That this frontier anthropologist renamed and categorized the Anishinaabeg. That this early scholar of “American Indian folklore” reworked living oral narratives into static specimens to be sold.

It was easy to do. I had been taught, in second grade, that The Song of Hiawatha was a real Indian story. Never was I taught that Schoolcraft and Longfellow’s works were actually false obituaries.

***

As governor of the Michigan Territory, Lewis Cass proposed an “exploratory tour” in the fall of 1819 through a domain that included what are now Wisconsin and part of Minnesota. He had political and “scientific” goals in mind. To determine if a water “communication” linked Lake Superior and the Mississippi River. To assess the allegiances of Anishinaabeg and other tribal peoples to the United States, and learn how they might respond to ceding land or sharing what remained with removed nations. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun added Schoolcraft to the expedition as mineralogist-geologist, to learn the truth of long-rumored copper deposits. The resulting reports would be among the first accounts describing mineral riches, arable soil, and potential freshwater fisheries there. All involved reached the “scientific” conclusion that the region was suitable for rapid expansion. The next step was to claim it.

The 1826 Council of Fond du Lac would be the first direct treaty negotiation between the Anishinaabeg around Madeline Island and the US government—the first of many to erode Indigenous rights to homeland.[4] “This copper does you no good,” Cass argued to tribal leaders, “and it would be useful to us to make into kettles, buttons, bells, and a great many other things.” Article 3 got to the point: “The Chippewa tribe grant to the Government of the United States the right to search for, and carry away, any metals or minerals from any part of their country.”

The 1842 La Pointe Treaty, in what the US then claimed as the Territory of Wisconsin, ordered that “Indians residing on the Mineral district, shall be subject to removal therefrom at the pleasure of the President of the United States.”[5] Although the treaty commissioner assured tribal leaders they could stay in their homeland for years to come, removals began as copper boomed. One ill-fated attempt late in 1850 left several hundred dead by disease, exposure, and hunger. Bands would resist, even sending delegations to Washington, DC.

The 1842 La Pointe Treaty, in what the US then claimed as the Territory of Wisconsin, ordered that “Indians residing on the Mineral district, shall be subject to removal therefrom at the pleasure of the President of the United States.”[5] Although the treaty commissioner assured tribal leaders they could stay in their homeland for years to come, removals began as copper boomed. One ill-fated attempt late in 1850 left several hundred dead by disease, exposure, and hunger. Bands would resist, even sending delegations to Washington, DC.

But in 1854 Wisconsin had been a state for six years. A few thousand Anishinaabeg gathered on Madeline Island that September to finalize the treaty ceding land on Lake Superior’s southern shore, and establishing reserved tracts in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota.[6] Gerald Vizenor’s ancestors were removed to the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota in 1868. Anishinaabeg people still negotiate for the right to use ceded land on the lakeshore in accordance with the 1842 and 1854 treaties. Mining continues to threaten treaty rights elsewhere.

***

The ancestral frameworks and most-aged rocks of the world’s continents lie within their nuclei, the Precambrian shields. As remnants of an inconceivably distant past, shields chronicle many evolutions: the early growth of continents, the origins of life, and an atmosphere gradually becoming habitable. The southernmost outcrops of North America’s core, the Canadian Shield, rim Lake Superior.

The Midcontinent Rift also lies exposed here. It, too, is another piece of North America’s ancient architecture, and geoscientists lean toward superlatives in describing a feature most people have never heard of. They say this rift is among the largest outpourings of lava in the world. It’s one of the longest ancient rifts on any continent, rivaling that in east Africa where our species emerged. The rift is also among the finest examples of a continent’s initial splitting apart that then “aborted” or stopped cold.

Watching days end from my friend’s beach, I realized that “scientific” research of the shield and rift began here because of what the bedrock contained. Men from Britain, France, and a fledgling United States “discovered” then deliberately sought copper and iron in the nineteenth century’s first decades. For some like Lt. Henry Wolsey Bayfield, who made the first accurate chart of Lake Superior for the British Royal Navy in the 1820s, the “objects of Geology” were “to seek among the ruins of strata for the only records of those awful events.” “These,” he added, “are only to be obtained by the accumulation of facts.”[7] By the 1880s geologists had accumulated many “facts” by tramping and mapping the lake’s mainland and islands. They described faults suggestive of Precambrian rifting. They recognized the terrain’s underlying structure. And, in 1911, the authors of The Geology of the Lake Superior Region, a 700-page monograph for the US Geological Survey, admitted the impetus of research: “The great development of the mineral industry in this region has afforded the geologist unusual opportunity for study, as it has not only made the region more accessible but has justified larger expenditures for geologic study than would otherwise have been made.”[8]

Paths toward understanding this landscape didn’t begin in a contextual vacuum, and published science’s specialized passive voice can frustrate a reader interested in agency. I came up short, in text after text, searching through “facts” underpinning current scientific models of the region’s most ancient past and origins of metal ores. Yet, on this southern shore of Lake Superior, one path drove and benefited from a state-sponsored search for minerals and the confinement of Anishinaabeg people in reservations. By 1890, less than half a century after the removals, the ceded lands led the world in copper mined.[9]

This past continues. The Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians now fights to remove an illegal oil pipeline that threatens not only tribal sovereignty but also the wild rice sloughs along the lakeshore that ancestors harvested for generations.

***

The events of one’s life take place. Our lives take place. In movements large and small. Of the Anishinaabeg becoming a people indigenous to the particularities of these woodlands and lakes. Of newcomers searching for minerals, settling the old Michigan and Wisconsin territories, displacing those so very long-placed. My time here measuring the motions of seasons and days.

Taking place has other dimensions, too. Of choices and practices aimed at possessing and controlling both territory and ideas of it. The pursuit of knowledge, of “scientific” research, was far from innocent as Indigenous traditions and people, as the land itself, were objectified and commodified, mined and collected. Any attempt to disentangle the search for copper or iron (or nickel or gold) from those first scientific studies, from treatied dispossessings, or from early American ethnography, is a fool’s errand.

In their mappings and renamings, agents from Europe and Euro-America claimed long-inhabited terrain. Schoolcraft, Lewis Cass, and others became experts by re-defining, re-positioning, re-presenting. Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha—once called a marker “of our literary independence” from Europe—appeared within a year of the treaty dispossessing the people whom the poem supposedly honored.[10] Yet lives and traditions of these tribal people remained an active evolving presence. Gerald Vizenor’s “survivance” is important here. Meaning more than survival, more than endurance or mere response, stories of survivance resist fixed categories or deadening stereotypes. “The shadows of tribal names and stories are the ventures of landscapes, even in the distance of translation,” he writes. “Tribal imagination, experience, and remembrance, are the real landscapes in the literature of this nation; discoveries and dominance are silence.”[11]

At Lake Superior’s shore I gazed at a self-reflection of old lessons and older silences, distortions, and absences. At seven I felt honored to know and trust a true “Indian” story in The Song of Hiawatha. My deep interest in America’s past and its places was propelled by fifth-grade lessons that romanticized Henry Schoolcraft’s exploits as heroic. Inventions clothed me.

On Madeline Island I began to catch up with the past. Dissecting learned stories can yield retrievable fragments of context and relationship, and reveal the vector of storying’s power—its direction, its magnitude, and its agency. I cannot be a complete stranger to a place such as this. These woodlands and I are partly effaced palimpsests. Altered in the passage of time, yes, but still retaining traces of earlier forms and origins. To understand the storying of any place, I must also understand the storying of my-self. I must follow traces beneath familiar surfaces to where ancestral structures lie.

Lauret E. Savoy is the David B. Truman Professor of Environmental Studies at Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape (Counterpoint Press, 2015, 2021). Her other books include Bedrock: Writers on the Wonders of Geology (Trinity University Press, 2006) and The Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity, and the Natural World (Milkweed Editions, 2011).

[1] Gerald Vizenor, “Shadows at La Pointe” in Touchwood (St. Paul: New Rivers Press, 1987), 130; and Gerald Vizenor, People Named Chippewa: Narrative Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 47.

[2] Gerald Vizenor, Everlasting Sky (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1972), 8.

[3] Vizenor, Everlasting Sky, 10.

[4] The 1826 Fond du Lac treaty can be found at https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-chippewa-1826-0268. For information on the sequence of treaties, see Ronald Satz, Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective (Madison: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991).

[5] The 1842 La Pointe treaty can be found at https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-chippewa-1842-0542.

[6] The 1854 treaty text is available at https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-chippewa-1854-0648.

[7] Commander Henry W. Bayfield, “Outlines of the Geology of Lake Superior,” Transactions of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, vol. 1 (1829), 4.

[8] Charles R. Van Hise and Charles K. Leith, The Geology of the Lake Superior Region (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, US Geological Survey, 1911).

[9] Robert Keller, “An Economic History of Indian Treaties in the Great Lakes Region,” American Indian Journal, Vol. 4 (February 1978), 2–20.

[10] In his book Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians (Philadelphia, 1856), which is dedicated to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Henry Schoolcraft suggested that Longfellow’s poem’s “theme of native lore reveals one of the true sources of our literary independence” from Europe.

[11] Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 10.