People and Nature in the American West: A Brief Deep History

by Sara Dant

The American West has long been a region of hope and renewal. Even now, at the vanguard of climate change and emblematic of a planet whipsawed by increasingly violent and destructive environmental crises, the West yet holds the extraordinary promise of modeling a sustainable future for the nation and the world. The writer Wallace Stegner foresaw this possibility, writing that “we are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate. But we are also the only species which, when it chooses to do so, will go to great effort to save what it might destroy.”[1]

The American West has long been a region of hope and renewal. Even now, at the vanguard of climate change and emblematic of a planet whipsawed by increasingly violent and destructive environmental crises, the West yet holds the extraordinary promise of modeling a sustainable future for the nation and the world. The writer Wallace Stegner foresaw this possibility, writing that “we are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate. But we are also the only species which, when it chooses to do so, will go to great effort to save what it might destroy.”[1]

A close examination of the deep history of the environment in the American West within the larger global context reveals how the unique geographies of the West have exerted such a powerful influence on the peoples of this region and how those people, in turn, have shaped and altered this largely arid land over time. The first humans to set foot on the North American continent arrived in the West and constantly innovated. New tools, the advent of agriculture, fire- and irrigation-managed environments, and the development of extensive trade routes were essential to early survival and success in the region and belie the myth of a pristine or Edenic America.[2]

In other words, by the time Europeans finally set foot in the Americas, Native peoples had flourished in the so-called “New World” for tens of thousands of years, largely sustainably, evolving societies ranging from subsistence hunting and gathering bands to sophisticated, agricultural, urban metropolises. Through careful management of scarce natural resources, they had wrested a living from sometimes harsh and formidable environments in the American West. Indigenous peoples also paid attention to changes in climate and rainfall and reacted accordingly. For example, approximately fifty-five hundred years ago, following the relatively wet and abundant Pleistocene epoch, the West experienced a profoundly dry and hot interval geologists call the Altithermal. Native peoples responded by moving away from the areas that could no longer sustain them.

In addition to aridity, a defining characteristic of the American West is its preponderance of public lands—roughly half of the federally managed domain lies in the eleven westernmost states. In the years following the 1783 American revolutionary victory, the nation’s territorial appetite proved insatiable. After a little more than a half century, the continental outline of the country looked as it does today. For this ever-ambitious nation, the key to extending American sovereignty from sea to shining sea was control over the land itself. To facilitate the efficient transfer of public lands into private hands, Congress passed a series of laws: the Homestead, General Mining, Desert Land, and Timber and Stone acts, for example.[3]

Historian Vernon Parrington called this giveaway “the Great Barbecue.” “Congress had rich gifts to bestow,” he argued, “in lands, tariffs, subsidies, favors of all sorts; and when influential citizens made their wishes known to the reigning statesmen, the sympathetic politicians were quick to turn the government into the fairy godmother the voters wanted it to be.”[4] By 1900, however, the myth of inexhaustibility gave way to the reality of diminished forests, waterways, and wildlife populations. Unfettered capitalism, it turned out, caused real environmental harm.

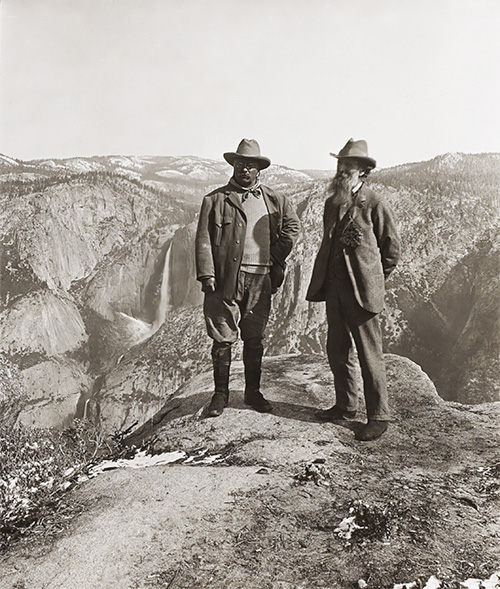

Federal management of the public lands thus came about as a consequence of the relentless pursuit of wealth that devastated so many ancient American ecosystems. At this critical juncture, Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office as the nation’s twenty-sixth president. An early and avid advocate for protecting wild places and wildlife, Roosevelt embraced the Progressive idea that the federal government was the best steward of the nation’s natural resources and guardian against rampant capitalist exploitation: essentially, the philosophy that public lands embody the greatest good for the greatest number.[5]

Federal management of the public lands thus came about as a consequence of the relentless pursuit of wealth that devastated so many ancient American ecosystems. At this critical juncture, Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office as the nation’s twenty-sixth president. An early and avid advocate for protecting wild places and wildlife, Roosevelt embraced the Progressive idea that the federal government was the best steward of the nation’s natural resources and guardian against rampant capitalist exploitation: essentially, the philosophy that public lands embody the greatest good for the greatest number.[5]

To manage the growing federal wildlife reserve system, Roosevelt consolidated several agencies into the Bureau of Biological Survey in 1905, which merged into the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1940. Also in 1905, Roosevelt transferred the country’s forest reserves into the newly minted US Forest Service. By 1916, the nation’s growing national parks system got their own National Park Service to control poaching and destruction. And in 1934, during the Depression and the Dust Bowl, the federal government began to sunset the homestead program and consolidate remaining public domain lands, ultimately, under the Bureau of Land Management in 1946.

Today, the federal government manages natural resources on these public lands across the nation as a kind of “commons” on behalf of all American citizens. So regardless of where you live, you are part-owner of 640 million acres—roughly twenty-eight percent of the country. Most agency protocols prioritize multiple use—the greatest good for the greatest number—and even the most restrictive designations, like wilderness or national parks, still allow activities such as camping, hunting, and fishing, and, in some limited cases, grazing and even mining.[6] These lands, said Stegner, constitute our “geography of hope.”[7]

Now, here in the twenty-first century, the greatest environmental threat to the West, the public lands, the nation, and the world is global climate change. The long-term rise in temperatures—the big-picture change over a century or more—rather than short-term variation, defines global climate change. Although the planet’s climate has always been in flux, cycling between ice ages and warmer epochs, what distinguishes recent trends is the rate of change. Nearly unanimous scientific evidence indicates that the principal cause of this warming trend is the rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and other heat-trapping greenhouse gases released during the Industrial Revolution. The primary source: the burning of fossil fuels.[8]

Some of the consequences of global climate change are already evident. In 2025, for example, the amount of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere was more than 50 percent higher than in preindustrial times. According to one climate scientist, these unsustainable CO2 levels will produce “ever more damaging levels of climate change, more heat waves, more flooding, more droughts, more large storms and higher sea levels.”[9] For the United States in 2024, climate-change-fueled disasters such as hurricanes and wild fires caused nearly $183 billion in damage.[10] Because the American West is at the vanguard of these environmental shifts, the need to develop a long-term sustainable relationship between people and nature in this region has become urgent.

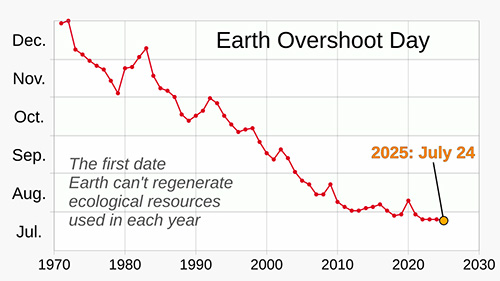

Earth Overshoot Day is an ecological footprint indicator that utilizes a yearlong calendar to identify the date on which human consumption of ecological services and resources “overshoots” the planet’s capacity for regeneration. It’s a rather ingenious, comprehensible sustainability index. Ideally, Earth Overshoot Day would fall on December 31. But in 2025, Earth Overshoot Day came on July 24. That means that it would take 1.8 earths to make us sustainable consumers. As recently as 1970, Earth Overshoot Day was December 23. For the United States, the statistics are even more grim. If all the world lived and consumed like the United States, Earth Overshoot Day would fall on March 13. In other words, just to sate our national demands would require five earths![11]

Earth Overshoot Day is an ecological footprint indicator that utilizes a yearlong calendar to identify the date on which human consumption of ecological services and resources “overshoots” the planet’s capacity for regeneration. It’s a rather ingenious, comprehensible sustainability index. Ideally, Earth Overshoot Day would fall on December 31. But in 2025, Earth Overshoot Day came on July 24. That means that it would take 1.8 earths to make us sustainable consumers. As recently as 1970, Earth Overshoot Day was December 23. For the United States, the statistics are even more grim. If all the world lived and consumed like the United States, Earth Overshoot Day would fall on March 13. In other words, just to sate our national demands would require five earths![11]

We’ve only got one.

As we move forward in the twenty-first century, strive for sustainability, and confront the effects of our long-term exploitation of the planet, the deep history of the West contextualizes the at-what-cost consequences of our environmental choices. Someone recently asked climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe if she believed in climate change. “I don’t believe in climate change,” she said. “Belief doesn’t come into it; scientific verification does. Gravity doesn’t care whether you believe in it or not, but if you step off a cliff, you’re going to go down.”[12] She remains relentlessly optimistic. “It’s not about saving the planet,” she argues, since “the actual planet will be orbiting the sun long after we’re gone. It’s about saving us.”[13]

There is reason to be hopeful. Despite the bitter divisions that pervade national politics, for example, a strong majority of Americans actually supports clean energy development, carbon emissions reduction, and a national commitment to addressing global warming. In a late 2024 survey of registered voters, for example, about sixty-three percent said “developing sources of clean energy should be a high or very high priority for the president and Congress.” Huge majorities supported tax incentives and rebates to encourage energy efficiency, believed corporations should “do more to address global warming,” and approved of “transitioning the U.S. economy from fossil fuels to 100% clean energy by 2050.”[14] The American West is at the vanguard of many of these initiatives.

The indomitable climate activist Greta Thunberg urges that “the one thing we need more than hope is action. Once we start to act, hope is everywhere.”[15] In the end, we all need clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment, which makes all of us environmentalists. Indeed, as Stegner reminds us, “one cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.”[16]

As its environmental history attests, the West abides.

Sara Dant is Brady Presidential Distinguished Professor Emeritus and professor emeritus of history at Weber State University. She is the author of Losing Eden: An Environmental History of the American West (University of Nebraska Press, new edition, 2023); the co-author, with Hal Rothman, of the two-volume Encyclopedia of American National Parks (Routledge, 2004); and an advisor and interviewee for the Ken Burns documentary film The American Buffalo (2023).

[1] Wallace Stegner, “The Marks of Human Passage,” in This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers, ed. Wallace Stegner (1955; Boulder, CO: Roberts Rinehart, 1985), 3–17.

[2] Excerpts from Sara Dant, Losing Eden: An Environmental History of the American West (University of Nebraska Press, new edition, 2023).

[3] Excerpts from Sara Dant, “Why Public Lands Should Stay Public and Protected,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 2025, available at https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2025-05-25/public-lands-national-parks-blm-monument-privatization-donald-trump.

[4] Vernon Louis Parrington, Main Currents in American Thought, vol. 3: The Beginnings of Critical Realism in America (New York, 1930), 23.

[5] Letter of James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture, to Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester in the Bureau of Forestry, concerning the management of the forest reserves [historians believe Pinchot authored the letter for Wilson’s signature], February 1, 1905, available at https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/policy-and%20-law/agency-organization/wilson-letter.

[6] Laura A. Hanson and Carol Hardy Vincent, “Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data,” February 21, 2020. Available at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R42346.

[7] Wallace Stegner, “Wilderness Letter” to David E. Pesonen, December 3, 1960, available at http://web.stanford.edu/~cbross/Ecospeak/wildernessletter.html.

[8] United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 ºC,” October 6, 2018, available at https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

[9] Doyle Rice, “Carbon Dioxide in Earth’s Atmosphere Soars to Levels Not Seen for Millions of Years, NOAA Says,” USA Today, June 3, 2022, available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2022/06/03/earth-carbon-dioxide-levels-noaa/7502392001/.

[10] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Assessing the U.S. Climate in 2024,” January 10, 2025, available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/national-climate-202413#:~:text=These%20disasters%20included:%2017%20severe,this%20disaster%20was%20$34.3%20billion.

[11] Earth Overshoot Day website, available at https://overshoot.footprintnetwork.org/.

[12] John Schwartz, “Katharine Hayhoe, a Climate Explainer Who Stays Above the Storm,” New York Times, October 10, 2016, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/11/science/katharine-hayhoe-climate-change-science.html.

[13] Somini Sengupta, “‘The Biggest Uncertainty Is Us’: Katharine Hayhoe, A Climate Scientist, Says Sustainable Choices Must Become the Easiest, Most Affordable Ones,” New York Times, June 24, 2022, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/climate/climate-forward-katharine-hayhoe.html.

[14]Anthony Leiserowitz, Edward Maibach, Seth Rosenthal, John Kotcher, Emily Goddard, Jennifer Carman, Teresa Myers, Marija Verner, Jennifer Marlon, Matthew Goldberg, Joshua Ettinger, Julia Fine and Kathryn Thier, “Climate Change in the American Mind: Politics & Policy, Fall 2024,” January 30, 2025, available at https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-in-the-american-mind-politics-policy-fall-2024/toc/3/.

[15] Greta Thunberg, “Greta Thunberg Ted Talk Transcript: School Strike for Climate,” December 12, 2018, available at https://www.rev.com/transcripts/greta-thunberg-ted-talk-transcript-school-strike-for-climate.

[16] Wallace Stegner, introduction to The Sound of Mountain Water: The Changing American West (New York: Vintage Books, 2017).