Yellowstone: National Parks as National Resources

by Megan Kate Nelson

If you have not been to Yellowstone National Park, you would probably recognize it in photographs and videos: The regular eruption of Old Faithful sending hot water and steam hundreds of feet into the air. The red, orange, yellow, and blue rings of Grand Prismatic Spring. The dark brown bubbling sludge of the Mud Volcano.

If you have not been to Yellowstone National Park, you would probably recognize it in photographs and videos: The regular eruption of Old Faithful sending hot water and steam hundreds of feet into the air. The red, orange, yellow, and blue rings of Grand Prismatic Spring. The dark brown bubbling sludge of the Mud Volcano.

Yellowstone National Park is best known for these geothermal features (although its bison herds and wolf packs are crowd pleasers as well). When Ferdinand Hayden, the first federally funded scientist to explore Yellowstone, saw its large geyser basins in the summer of 1871, he knew they were unique in all the world. He featured them in his proposal to Congress, to save Yellowstone as the nation’s first national park.

To convince national politicians to set aside these lands for public use, however, was no easy feat.

In 1871–1872, America was in the midst of a national Reconstruction. The country was still reeling—politically, economically, and culturally—from the American Civil War. And a group of conservative lawmakers were determined to heal the nation not by preserving a natural wonder, but by opening all American lands to development.

***

Although Yellowstone was terra incognita to most White Americans in the 1870s, it was well known to many Indigenous peoples.

For thousands of years, more than twenty tribal nations had been using the Yellowstone Basin as a thoroughfare, a hunting ground, a site of medicinal herb collection, and a ceremonial ground. The Tukudeka Shoshone considered Yellowstone their homeland, raising sheep and living in villages in the Basin’s mountain valleys.[1]

White Americans began to enter Yellowstone in the early nineteenth century. Fur traders and trappers came first, but no one believed the stories they told about water exploding out of the ground and technicolor hot springs. Then a gold rush brought thousands of miners to Montana in 1863, and by the end of the decade, curious civilians began to launch explorations of Yellowstone.[2]

In the fall of 1870, Ferdinand Hayden, a scrappy and ambitious geologist and federal surveyor, heard about these amateur explorations and knew he had to act immediately if he wanted to claim Yellowstone for science.[3]

During the spring 1871 congressional session, Hayden lobbied senators and congressmen to fund an expedition to Yellowstone. He succeeded; they gave him $40,000 to hire team members and supply them for the trip. At this point, neither Hayden nor the members of Congress were thinking about preserving Yellowstone as a national park. The US government wanted Hayden to report on the Basin’s suitability for farming, ranching, mining, and other forms of development.[4]

Within the month, Hayden hired scientists, guides, and packers. He also recruited an illustrator, a painter, and a photographer. His team took the Union Pacific railroad (completed in 1869) to Ogden, Utah, and then headed north into Idaho and Montana on horseback.[5]

Within the month, Hayden hired scientists, guides, and packers. He also recruited an illustrator, a painter, and a photographer. His team took the Union Pacific railroad (completed in 1869) to Ogden, Utah, and then headed north into Idaho and Montana on horseback.[5]

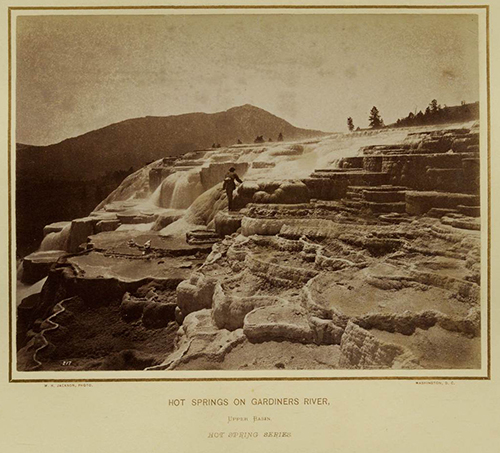

Once they arrived in Yellowstone Basin in July 1871, the survey team explored all its natural features. They took samples of earth and water, collected rocks and plants, and theorized about the geological forces that had created such a fabulous place. The photographer (William Henry Jackson) set up his camera and mobile darkroom and took hundreds of photographs, while the artist (Thomas Moran) painted the vistas with watercolors in vivid shades of blue, pink, yellow, and green.[6]

By late October, Ferdinand Hayden was back in Washington, DC. He sent reports and forty-five boxes of specimens to the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of the Interior and wrote articles about the expedition’s discoveries for Scribner’s Monthly and the American Journal of Science.[7]

Then, prompted by Jay Cooke, a millionaire and investor in the Northern Pacific Railroad looking to boost tourist traffic to the region, Hayden began to lobby Congress to pass an act to preserve Yellowstone as a national park.[8]

***

The Yellowstone Park Protection Act, which was introduced in December 1871 and debated in Congress in January and February 1872, proposed a massive land-taking.

The Yellowstone Park Protection Act, which was introduced in December 1871 and debated in Congress in January and February 1872, proposed a massive land-taking.

The Department of the Interior would take more than 3,400 square miles in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming Territory and manage them as protected federal land, for the “benefit and enjoyment of the people.”[9] There were no provisions in the act to negotiate with the many Indigenous peoples who claimed the area. In 1871, Congress had passed legislation ending treaty-making with tribal nations.

Although many Americans today believe national parks are a positive good for society, in 1872 the Yellowstone Act was controversial.

Some lawmakers objected that the Yellowstone Act would infringe upon the rights of White settlers to claim land in the West. These rights were enshrined in preemption and squatters’ laws and in legislation like the Homestead Act, passed in 1862 to provide land for all citizens loyal to the United States during the Civil War.

Other congressmen believed that the creation of the park was a dangerous form of federal government overreach. Since 1865, Radical Republicans had pushed through a series of Reconstruction Acts that expanded and protected the rights of American citizens across the country. Democrats opposed this growing federal power, and even some moderate Republicans were wary.[10]

The House roll call on February 27, 1872, revealed that 89 percent of Republicans voted yes, and 70 percent of Democrats voted no.[11] The Republicans’ strong majority in the post–Civil War House meant that the Yellowstone Act—bipartisan but certainly not unanimous—passed. On March 1, 1872, the bill landed on President Ulysses S. Grant’s desk, and he signed it without any fanfare.[12]

***

That spring, the US Congress gave Ferdinand Hayden $75,000 for a second Yellowstone Expedition. He set out with a team twice as large as the year before, intent on gathering more specimens and determining Yellowstone’s place in the earth’s geohistory.[13]

Few other Americans saw Yellowstone for the next ten years, however.[14] Tourists did not come to the area in large numbers until the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883. At that point, annual tourist numbers jumped from 1,000 to 5,000. In 1948, Yellowstone welcomed one million visitors for the first time and today, more than four million people drive and hike through the nation’s first national park every year.[15]

And yet, corporations continue to make bids to mine for gold on the edges of Yellowstone, or to extract its geothermal energy to provide power for local residents. Conservative politicians continue to oppose the preservation of national park lands and have recently sought to remove their protected status and allow development within them.

Americans continue to fight over whether places like Yellowstone—or the Grand Canyon or Denali or Death Valley—are natural resources that must provide a commodity to buy and sell, or if they are different kinds of resources: places where all Americans can go to learn about science, admire beautiful landscapes, and immerse themselves in nature.

***

National parks have many complex histories, and each one of them is different.

Yellowstone’s history shows us that Indigenous peoples have been responsible stewards of the land for thousands of years. And yet federal and state governments rarely respected their experience, or their rights to claim their homelands. National park creation has always required Indigenous land dispossession.

It shows us that national parks are not a given. The arguments that opponents of the Yellowstone Act made in 1872 are still made today to remove preservation status from public lands for development.

And it shows us that the period of Reconstruction was not only about bringing the South back into the Union. It was also about controlling the West and all its natural resources.

This history of Yellowstone is what we call “hard history.”

It is not meant to undermine or contradict the love that we all have for this place, and our wonder at its beauty. Instead, it reminds us that all Americans must understand how national parks came to be, to truly understand the fullness of the country’s environmental histories, past and present.

Megan Kate Nelson is an award-winning writer and historian. She is the author of The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West (Scribner, 2020), Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America (Scribner, 2022), and The Westerners: Myth-Making and Belonging on the American Frontier (Scribner, forthcoming April 2026).

[1] Peter Nabokov and Lawrence Loendorf, American Indians and Yellowstone National Park: A Documentary Overview (Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming: National Park Service, 2002), 101–103.

[2] Hiram Martin Chittenden, The Yellowstone National Park: Historical and Descriptive (Cincinnati: Stewart & Kidd Company, 1918), 14, 40; Gustavus C. Doane, “Report of Gustavus C. Doane Upon the So-Called Yellowstone Expedition of 1870,” submitted February 24, 1871 (41st Congress, 3rd Session, Senate Executive Document No. 5), 8–9; Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 83, 85; Aubrey L. Haines, The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park, 2 vols. (Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming: Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, 1977), 1: 94.

[3] Mike Foster, Strange Genius: The Life of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (Niwot, Colorado: Robert Rinehart, 1994), 4, 14–15; James G. Cassidy, Ferdinand V. Hayden: Entrepreneur of Science (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 34–37.

[4] Sundry Civil Bill (March 3, 1871), Statutes at Large, 41st Congress, 3rd Session, Chapter 114, 503.

[5] Jeremy Vetter, Field Life: Science in the American West during the Railroad Era (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016), 6, 8, 9, 12.

[6] For an extended treatment of the details of the expedition, see Megan Kate Nelson, Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America (New York: Scribner, 2022).

[7] Foster, Strange Genius, 213; Cassidy, Ferdinand V. Hayden, 207.

[8] A. B. Nettleton to Ferdinand Hayden, October 27, 1871, NARA RG 57.2.3, LR Vol. 3; Haines, The Yellowstone Story, 1: 155, 165.

[9] The Yellowstone National Park Act (S.392), signed March 1, 1872. From U.S. Statutes at Large, Vol. 17, Chap. 24, 32–33.

[10] “Yellowstone Park,” January 30, 1872, The Congressional Globe, Senate, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, 697; Haines, The Yellowstone Story, 1: 170; Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, 176; Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, January 30, 1872, 248.

[11] Roll Call, February 27, 1871, Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, 410–411; Haines, The Yellowstone Story, 1: 172.

[12] Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, pp. 286, 299, 324; The Congressional Globe, 1871–1872, 1228, 1416.

[13] Statutes at Large, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, Chap. 415, 350.

[14] Jacoby, Crimes against Nature, 88.

[15] Haines, The Yellowstone Story, vol. 2, Appendix C: Statistical, 478–480.