How City Parks Came to Resemble What They Are Today

by Catherine McNeur

Walk into a city park today, and it is immediately evident how these public spaces hold many different purposes. They are where joggers, dog walkers, and bicyclists weave around each other on paths, and children shriek and scream as they chase a new friend or swing higher than they ever have before. They are landmarks for picnics and birthday parties, as well as concerts, protests, and rallies. They are also quiet escapes to find a bench and read a book, or simply readjust eyesight, smell flowers, and listen to birdsong. Whether or not parks encompass other institutions like museums or zoos, they remain attractions that draw tourists looking to experience something authentic and noncommercial during their visit. They are also contested spaces where politicians, police, and residents debate how they can be used: everything from who is allowed to fall asleep there to whether dogs can run off leash. In short, parks are vibrant and complex places filled with many overlapping uses and meanings. They are microcosms of their cities and communities.

Walk into a city park today, and it is immediately evident how these public spaces hold many different purposes. They are where joggers, dog walkers, and bicyclists weave around each other on paths, and children shriek and scream as they chase a new friend or swing higher than they ever have before. They are landmarks for picnics and birthday parties, as well as concerts, protests, and rallies. They are also quiet escapes to find a bench and read a book, or simply readjust eyesight, smell flowers, and listen to birdsong. Whether or not parks encompass other institutions like museums or zoos, they remain attractions that draw tourists looking to experience something authentic and noncommercial during their visit. They are also contested spaces where politicians, police, and residents debate how they can be used: everything from who is allowed to fall asleep there to whether dogs can run off leash. In short, parks are vibrant and complex places filled with many overlapping uses and meanings. They are microcosms of their cities and communities.

I once took for granted that this is how parks have always been. When I began researching the environmental history of antebellum Manhattan, however, I saw how beliefs about city parks and public spaces changed dramatically during the early nineteenth century, resulting in something closer to what we know today.[1] Other early American cities (Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, etc.) went through similar transformations, so New York was not unique.[2] That said, given the rapid urbanization of the city thanks to the migration of rural Americans and immigrants, some of the debates over parks and their purposes lit up with controversy faster than in other cities, and consequently set an example for many of the western cities developing later in the century as newspaper coverage shared lessons and guidance.

In 1811, city leaders did not see much need for parks in New York. The commissioners who were tasked with designing the plan for Manhattan that resulted in its grid believed parks were primarily useful for air circulation. Thanks to the “large arms of the sea which embrace” the island, the commissioners felt like there was plenty of good air already. Paris and London might have parks, the commissioners conceded, but that was only because the Seine and Thames were “small stream[s]” compared to New York’s Hudson and East Rivers. Still, the commissioners reserved a few spaces for parks that were on privately owned land. The cash-strapped city government eventually whittled these limited parks down even more after property owners balked and the price of real estate rose higher.[3]

No matter the commissioners’ dismissal of Paris and London, comparisons to European capitals haunted New Yorkers’ sense of their own city. Fear that Manhattan wasn’t measuring up led journalists and city residents to take parks seriously. They wanted parks to serve as ornaments to show the city’s maturity, culture, and pride. They wanted European tourists to recognize that Americans were their equals.

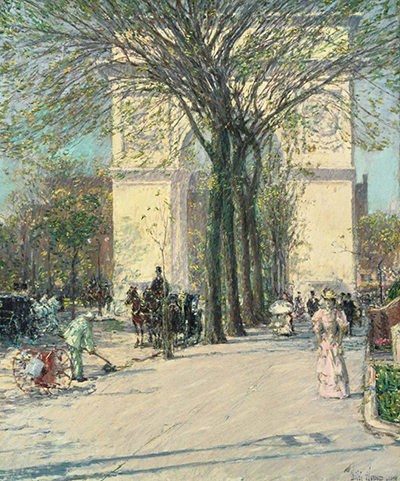

The creation of Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village helped to make their argument with city leaders. Developed on land originally used for a potter’s field and military parade ground, it was a rare open space in the increasingly urbanized city of the 1820s. Transforming it into a park meant planting shade trees and shrubbery, clearing paths, building a fence, and eventually installing a fountain. Soon after it opened to the public in 1827, the neighborhood surrounding it grew popular and the new, fashionable rowhouses nearby were in high demand. City politicians reveled in what this meant for their own budget as property taxes skyrocketed.[4]

The municipal government was eager to replicate this with both public and private parks. Focused primarily on real estate values and property taxes, they were essentially hoping to gentrify neighborhoods. The new parks were designed to be elite spaces where the wealthy could promenade and admire each other’s fashions.[5] The city paid for them with special assessments—a kind of tax levied on residents who lived nearby. The councilmen saw this as fair, given that local residents would benefit most from the new parks. The funding system, however, meant that not all New Yorkers had equal access to green spaces, since poorer neighborhoods could not afford them. Environmental justice, in other words, was not a priority.[6]

Parks would become more than simply a tool for property values thanks in large part to several challenges facing Manhattan in the 1830s and 1840s. Cholera ravaged cities across the world including New York in these decades. Before germ theory, people believed that diseases were transmitted by miasmas, or foul, contaminated air. Parks and other open spaces were like firebreaks for disease and many who escaped illness gave credit to the fresh air in their nearby parks, even though cholera was actually transmitted through contaminated water.[7] During the same time period, a rush of immigration from political uprisings and famine in Europe led to widespread and visible poverty on the streets of New York as the city struggled to house and employ the surge of new residents.[8]

When the landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing made a compelling plea for a new, big park in the city in 1851, it was no wonder then that he referred to its potential as “a breathing zone, and healthful place” where people across social classes could “grow into social freedom by the very influences of easy intercourse, space and beauty, that surround them.”[9] When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed their winning plan for Central Park, they echoed Downing’s hopes that the space would be for all New Yorkers and in turn would solve the city’s social and public health problems.  Central Park truly emerged from the challenges New York had faced in the decades prior. Creating a space meant to embody these ideals also involved the dispossession of Seneca Village’s Black and Irish residents, as well as the German farmers working the land in the southern part of the park. The dreams and reality collided in messy ways. Even New Yorkers who had used the land as a commons—harvesting food and fuel, pasturing animals, and more—found that they were newly excluded from continuing to do so by professional park police with a list of rules in their pockets.[10]

Central Park truly emerged from the challenges New York had faced in the decades prior. Creating a space meant to embody these ideals also involved the dispossession of Seneca Village’s Black and Irish residents, as well as the German farmers working the land in the southern part of the park. The dreams and reality collided in messy ways. Even New Yorkers who had used the land as a commons—harvesting food and fuel, pasturing animals, and more—found that they were newly excluded from continuing to do so by professional park police with a list of rules in their pockets.[10]

In the generations to follow, parks would continue to evolve to match the priorities of New Yorkers at different moments. The city government introduced the Small Parks Act in 1887, focusing more on equity and accessibility, albeit sometimes doing so against the neighborhoods’ wishes.[11] Playgrounds would become more of a focus in the early twentieth century with the nationwide playground movement, and Parks Departments would increasingly focus on recreation programs and facilities in the mid-twentieth century.[12] In the last several decades, parks and playgrounds have become increasingly accessible for disabled visitors with plenty of room for continued improvement. Parks are ever evolving, and our concerns about urban heat and biodiversity will certainly impact landscape designs in years to come.

The way we design and redesign parks, and, even more importantly, how we use them, reflects our current response to challenges and our understanding of what people need. Early nineteenth-century New York highlights these changes at a moment when the city and its people were rapidly transforming too, calling for new kinds of spaces and envisioning what they could do. Parks will forever be what we make of them.

Catherine McNeur is a professor of history at Portland State University in Oregon. She is the award-winning author of Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City (Harvard University Press, 2014) and Mischievous Creatures: The Forgotten Sisters Who Transformed Early American Science (Basic Books, 2023).

[1] Catherine McNeur, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City (Harvard University Press, 2014).

[2] See, for instance, Michael Rawson, Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston (Harvard University Press, 2010).

[3] William Bridges, Map of the City of New-York and Island of Manhattan; With Explanatory Remarks and References (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1811), 25–28.

[4] “Document No. XXXVII,” Documents of the Board of Assistants (New York: Printed by Order of the Common Council, 1837) I: 125–133.

[5] David Scobey, “Anatomy of a Promenade: The Politics of Bourgeois Sociability in Nineteenth-Century New York,” Social History 17.2 (1992): 203–227.

[6] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 45–94.

[7] Melanie Kiechle, Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), 21–52; McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 95–133; Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962; repr. 1987).

[8] George G. Foster, New York in Slices (New York: W. F. Burgess, 1849); Robert Ernst, Immigrant Life in New York City, 1825–1863 (New York: King’s Crown Press, 1949); Edward K. Spann, The New Metropolis: New York City, 1840–1857 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), chapter 2; Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1789–1860 (New York: Knopf, 1986); Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

[9] Andrew Jackson Downing, “The New-York Park,” Horticulturist 6.8 (1 August 1851): 315–319.

[10] New York (N.Y.) Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, Second Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park (New York: Wm. C. Bryant, 1859), 60–68; New York (N.Y.) Board of Commissioners of Central Park, Third Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park (New York: Wm. C. Bryant & Co., 1859), 17–19; Alexander Manevitz, “The Rise and Fall of Seneca Village: Race and Space on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century New York City,” Ph.D. Dissertation, New York University, 2016; Jason Jindrich, “The Shantytowns of Central Park West,” Journal of Urban History 36.5 (2010): 672–684; Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).

[11] Adrienne deNoyelles, The Lung Block: Plagues, Parks, and Power in Progressive-Era New York (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024); Marika Plater, “Escaping Gotham: Working People and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle over Urban Nature,” PhD Dissertation, Rutgers University, 2021.

[12] Ocean Howell, “Play Pays: Urban Land Politics and Playgrounds in the United States, 1900–1930,” Journal of Urban History 34.5 (2008): 961–994; Natalie Novoa, “Defining Race, Space, and Citizenship through Play: The Playground Movement in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1900–1920,” Journal of Urban History (December 2024).