Climate Anxiety, Climate Ambition, and Early American Infrastructure

by Keith Pluymers

![David J. Kennedy (ca. 1816–1898) after Thomas Birch, "Dead House on the Schuylkill during the Yellow Fever in Philadel[phia] in 1793," watercolor, n.d. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Digital Library)](/sites/default/files/2025-09/Kennedy_DeadHouse_HSP.jpg) Chapter 12 of the US Global Change Research Program’s Fifth National Climate Assessment (2023) praised city governments for adopting “forward-looking infrastructure designs” to adapt to and mitigate the harms from climate change and called for more cities to creatively link social, technological, and ecological components of infrastructure together to protect, among other things, public health. City governments and urban residents are facing the challenge of unprecedented anthropogenic climate change, and urban infrastructure is, according to the authors of the report, a crucial tool in mitigating or adapting to it.

Chapter 12 of the US Global Change Research Program’s Fifth National Climate Assessment (2023) praised city governments for adopting “forward-looking infrastructure designs” to adapt to and mitigate the harms from climate change and called for more cities to creatively link social, technological, and ecological components of infrastructure together to protect, among other things, public health. City governments and urban residents are facing the challenge of unprecedented anthropogenic climate change, and urban infrastructure is, according to the authors of the report, a crucial tool in mitigating or adapting to it.

The scale and risk of current anthropogenic climate change is indeed unprecedented, but concerns about climate and public health and the desire for innovative infrastructure to mitigate climate woes was a foundational problem for the United States.

In December 1797, after multiple deadly waves of yellow fever ripped through Philadelphia, then serving as the new country’s temporary capital, physician and Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Rush and a group of Philadelphia physicians warned, “At present a constitution of the atmosphere prevails in the United States which disposes to fever of a highly inflammatory character.” Yellow fever was, they believed, a disease that depended upon the combination of hot weather and “putrefaction,” or decay and decomposition of plant matter or rubbish in ways that either emitted harmful vapors or altered the chemical composition of the atmosphere in disease-producing ways. Rush and others feared that the American climate was changing in dangerous and uncertain ways that made epidemics more likely.[1]

This marked an escalation of earlier anxieties. Benjamin Franklin’s concerns about climatic instability played a role in his efforts to design stoves for efficient domestic heating.[2] Rush had been concerned about unstable weather patterns and disease for more than a decade prior to co-authoring the report and believed that the actions of Pennsylvania settlers played a role. In a 1785 essay published in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, the scholarly journal of one of the leading scientific societies of the eighteenth century,  Rush warned that the combination of rapid deforestation, the creation of standing water in millponds, and atypical patterns of rainfall over several years had created a perfect environment for “marsh effluvia” and “febrile miasmata” to spread epidemic fevers. But this pattern could be eliminated over time. Planting trees, particularly around millponds, would filter and purify the air. Balancing settlers’ destructive clearances of healthy but wild land with “cultivation”—planting crops, draining marshes, and destroying weeds—would ensure that there was not an excess of territory that would produce diseases. In this essay, Rush had claimed that cities were far less likely than rural areas to experience epidemic and endemic fevers, despite changes to Pennsylvania’s atmosphere. As a result, his proposed solutions largely focused on the countryside.

Rush warned that the combination of rapid deforestation, the creation of standing water in millponds, and atypical patterns of rainfall over several years had created a perfect environment for “marsh effluvia” and “febrile miasmata” to spread epidemic fevers. But this pattern could be eliminated over time. Planting trees, particularly around millponds, would filter and purify the air. Balancing settlers’ destructive clearances of healthy but wild land with “cultivation”—planting crops, draining marshes, and destroying weeds—would ensure that there was not an excess of territory that would produce diseases. In this essay, Rush had claimed that cities were far less likely than rural areas to experience epidemic and endemic fevers, despite changes to Pennsylvania’s atmosphere. As a result, his proposed solutions largely focused on the countryside.

Multiple epidemics in Philadelphia demanded something different.

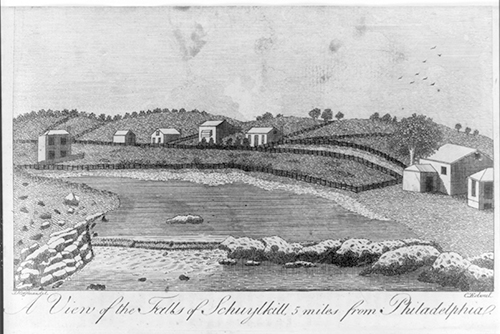

In the later 1790s, there were multiple proposals to address hot temperatures, stagnant air, and, most ambitiously, the composition of the atmosphere through the development of urban infrastructure. The first of these, a 1795 proposal to the American Philosophical Society from French-born architect Charles Varlé, treated the network of municipal wells and pumps as a water supply capable of supporting new, innovative infrastructure. Varlé called for the installation of new pumping engines atop the wells capable of moving water into elevated pipes that could irrigate gardens and fight fires. Additionally, moving piped water through Philadelphia’s buildings would cool interior rooms (essentially a vision of water-powered air conditioning). This could help “prevent in the city the diseases of the summer occasioned partly by the intemperance of the season.” By 1798, although still advocating for artificial rain to purify the air, he soured on municipal wells, calling instead for a series of aqueducts to carry water from the Schuylkill River into the city and canals to carry waste out of it.[3]

Other individuals publicly advocated for a new water supply. A widely circulated proposal to the naturalist and physician Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton to prevent yellow fever in Philadelphia called for the creation of a gravity-fed, piped water supply. The author, J. Sullivan, lamented that Philadelphia’s “atmosphere is not agitated by the sea-breezes which we complain of in Boston,” resulting in oven-like conditions and unbreathable, stagnant air as heat reflected off the city’s bricks. Sullivan claimed he “need not dwell” on the exact relationship between seasonal weather, climate, wind, and disease, but claimed “the remedy” was clear—an aqueduct that would carry Schuylkill River water to Philadelphia.

The most elaborate of these proposals came from architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, whose later work included the US Capitol. Latrobe promised not only to provide “a sufficiency of wholesome water for culinary purposes” but also “washing the streets, and, if possible, of cooling the air of the city.” To do so, Latrobe proposed a series of “fountains” (his admittedly grandiose name for “a short wooden pipe, set perpendicularly into the main, and stopped by a cock”) positioned around the city. Operating together, the effects could be dramatic. “Agitation of water” produced air of the “purest kind” and “the sudden evaporation of water, scattered through the air, absorbs astonishing quantities of heat,—or to use the common phrase, creates a great degree of cold.”[4] This was a systematic effort to control air quality and temperature across the city.

Climate was at the heart of Latrobe’s proposal. Philadelphia, according to Latrobe, had a climate characterized by extremes. There were bitterly cold winters in which rivers froze solid; destructive “freshes” in which spring floods and ice floes swelled rivers, and wet summers that could overwhelm infrastructure. Extreme cold was a particular risk that he claimed ruled out some proposed technologies, including those like aqueducts or water-powered pumps that functioned well in European cities. Elsewhere, he warned about the “hot climate” dangerous to Americans with “Northern ancestors.” Unlike residents of “many despotic countries,” Philadelphians did not have public baths, fountains, or other water infrastructure to mitigate heat, nor, he lamented, were they likely to adopt it due to a desire for “industry.”[5] Since Americans were unlikely to adapt their lifestyle to a hot climate, Latrobe recommended for the city of Philadelphia water infrastructure that would adapt climate to American habits.

There was, he claimed, only one technology capable of delivering a water system that could provide all of these benefits—the steam engine.

Latrobe’s proposal was persuasive. Philadelphia’s city government adopted it and built the waterworks at Centre Square, hailed as the first piped municipal water system in the United States. Before that project was completed, Latrobe publicly abandoned his claims about atmospheric control, brazenly stating that he had never made any claims about artificial cooling. Despite his disavowal, the hope that piped water systems could ameliorate the atmosphere remained. In 1819, when Philadelphia’s Watering Committee announced its intention to abandon steam for a water-wheel, they noted that the increased power of their new engines would finally enable them to create “an elasticity in the air so necessary to health” during “extreme hot weather.”[6]

Latrobe’s proposal was persuasive. Philadelphia’s city government adopted it and built the waterworks at Centre Square, hailed as the first piped municipal water system in the United States. Before that project was completed, Latrobe publicly abandoned his claims about atmospheric control, brazenly stating that he had never made any claims about artificial cooling. Despite his disavowal, the hope that piped water systems could ameliorate the atmosphere remained. In 1819, when Philadelphia’s Watering Committee announced its intention to abandon steam for a water-wheel, they noted that the increased power of their new engines would finally enable them to create “an elasticity in the air so necessary to health” during “extreme hot weather.”[6]

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, piped water systems represented major investments that posed political as well as technological and financial challenges, as they continue to do today.[7] In Philadelphia, the development of urban water infrastructure and climate thinking were inextricably linked. Today, we face the challenge of re-integrating infrastructure, climate, and public health. How to do so is a new challenge, but efforts to make these connections are much older.

Keith Pluymers is associate professor of history at Illinois State University. He is the author of No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021).

[1] Benjamin Rush and Associates, Physicians of Philadelphia, “Report to the Governor . . . on the Nature and Origin of the Late Contagious Disease” (December 1797), 3, Benjamin Rush Papers, MSS 2/0096-01, Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia; Jan Golinski, “Debating the Atmospheric Constitution: Yellow Fever and the American Climate,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 49, no. 2 (2016): 149–165, https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2016.0011.

[2] Joyce E. Chaplin, The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025).

[3] Charles Varlé, “Plan for Extinguishing Fires,” March 6, 1795, APS.Archives.III.1, Box 6, American Philosophical Society; Charles Varlé, “Réflexions Sur Les Causes de La Fièvre Jaune de Philadelphie, et Sur Les Moyens Den Préserver Les Habitants,” 1798, APS.Archives.III.1, OS, American Philosophical Society.

[4] Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View of the Practicability and Means of Supplying the City of Philadelphia with Wholesome Water in a Letter to John Miller, Esquire, from B. Henry Latrobe, Engineer. December 29th, 1798 (Zachariah Poulson, Jr., 1799), 3, 18.

[5] Latrobe, View of the Practicability, 3, 14, 19.

[6] Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Remarks on the Address of the Committee of the Delaware and Schuylkill Canal Company to the Committee of the Senate and House of Representatives, As Far as It Notices the “View of the Practicability and Means of Supplying the City of Philadelphia with Wholesome Water” (Zachariah Poulson, Jr., 1799), 8–9; An Additional Report, on Water Power, by the Watering Committee: With Communications on the Subject from Messrs. Ariel Cooley, Lewis Wernwag, Thomas Oakes, William Briggs, and William Lehman. And Other Documents (William Fry, 1819), 5.

[7] Carl S. Smith, City Water, City Life: Water and the Infrastructure of Ideas in Urbanizing Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2013).