Different Ways of Reforming the Electoral College: Past and Present

by Alexander Keyssar

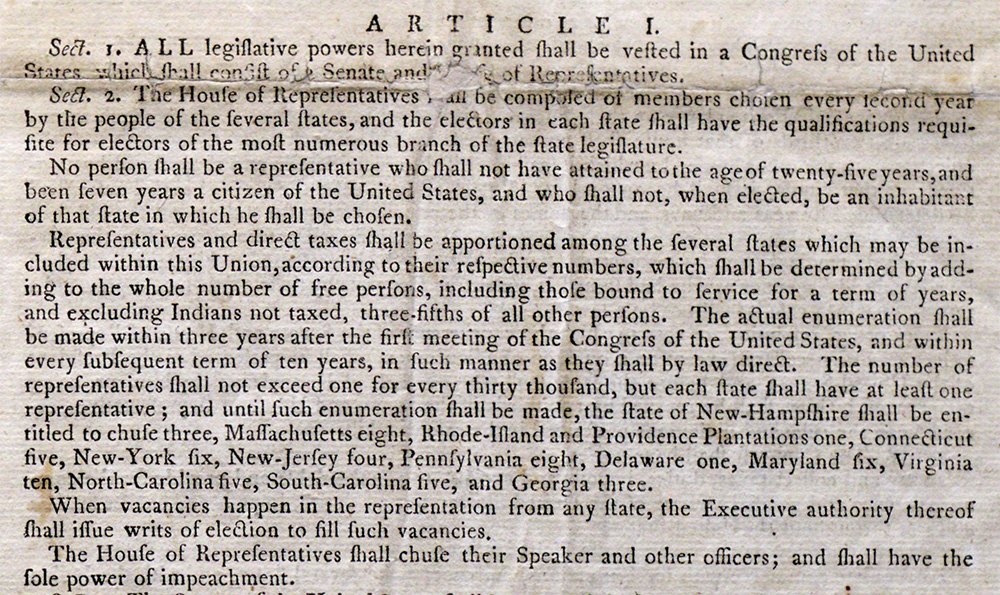

Serious efforts to reform the Electoral College began not long after the US Constitution was ratified. Our complex mechanism for electing presidents, which we now call the Electoral College (the phrase does not appear in the Constitution), was widely criticized throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and into the twenty-first. More constitutional amendments to change, or abolish, the institution have been introduced in Congress than on any other subject. A half dozen of these—as early as 1813 and as recently as 1969—were approved by a two-thirds vote of one chamber of Congress.[1]

Serious efforts to reform the Electoral College began not long after the US Constitution was ratified. Our complex mechanism for electing presidents, which we now call the Electoral College (the phrase does not appear in the Constitution), was widely criticized throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and into the twenty-first. More constitutional amendments to change, or abolish, the institution have been introduced in Congress than on any other subject. A half dozen of these—as early as 1813 and as recently as 1969—were approved by a two-thirds vote of one chamber of Congress.[1]

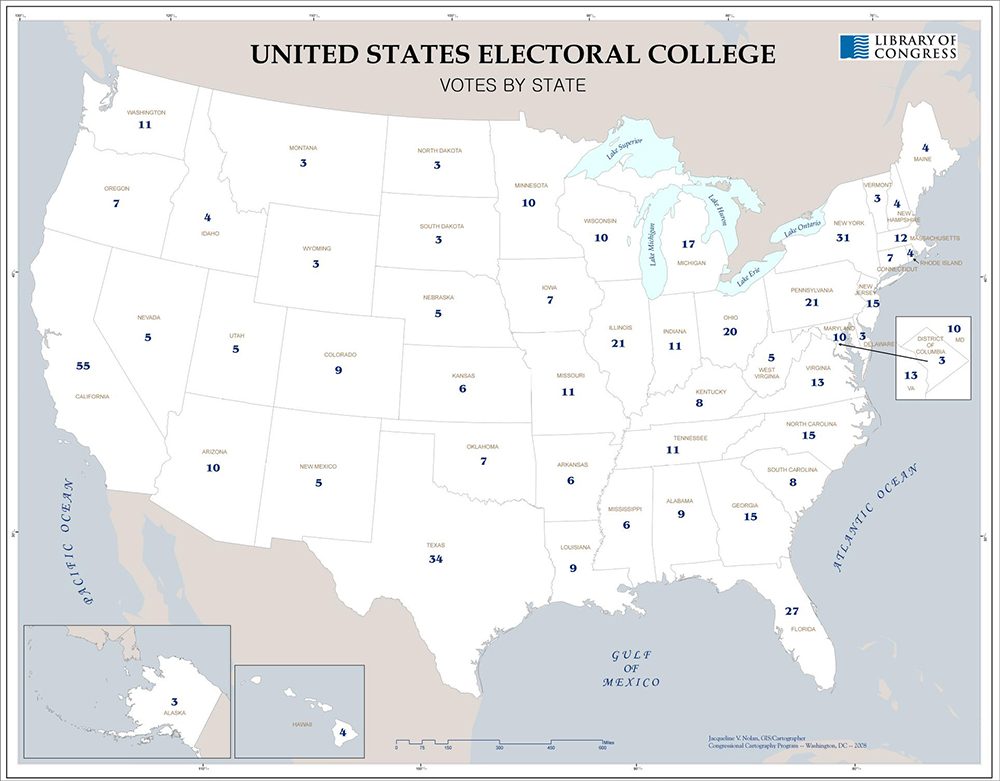

One approach to reform is (and has been) to get rid of “winner-take-all”—the practice of awarding all of a state’s electoral votes to the winner of that state’s popular vote. Notably, winner-take-all is not mandated by the Constitution itself: that document left it to the states to decide how to allocate electoral votes (and even whether to have popular elections to do so). During the first decades of our history, states experimented with different methods: choosing electors in statewide elections, or through some version of districting elections, or by state legislatures acting alone. Gradually winner-take-all (which was then called the “general ticket”) became the default method, as each state sought to maximize its influence in the national election.

But many political leaders and critics, in the nineteenth century and ever since, have regarded winner-take-all as the most damaging, and undemocratic, feature of our electoral system. It has meant that contests in many states were not—and are not—competitive and consequently are ignored by presidential campaigns. At the same time, competitive or “swing states” became the arena of excessively fierce battles. Winner-take-all also increases the odds of a “wrong winner” election, i.e., one in which the candidate with the most popular votes does not win a majority of Electoral College votes and thus does not take office.[2]

The most commonly proposed method of eliminating winner-take-all has been to amend the Constitution to require that electors be allocated by district, often by having one elector selected by the voters of each congressional district and two additional electors awarded to the winner of the state’s popular vote. (The number of electoral votes given to each state is equal to the number of its members in the House of Representatives plus two, for its two US senators). This was the most popular proposal in the nineteenth century, and it had significant support in Congress and in the nation at large. In 1821‒1822, for example, an amendment supporting this reform was approved by the Senate and fell only a few votes short of the requisite two-thirds in the House.[3] The idea resurfaced from time to time in the twentieth century and still circulates today.

A somewhat different approach to this problem would be to choose electors through a “proportional” system: a presidential candidate receives electoral votes from a state in proportion to the percentage of the state’s popular vote that s/he has won. This idea gained strength beginning in the late nineteenth century as political leaders began to worry about the severe gerrymandering of congressional (and other) districts; they feared that district elections would import the problem of gerrymandering into presidential elections. Proportional elections could avoid that problem, and that idea retains many adherents today. An amendment calling for proportional elections was approved by the Senate in 1950.

From time to time, individual states have also considered taking action to discard winner-take-all by themselves—which they are permitted to do by the Constitution. Michigan adopted such a change in the 1890s (although it was quickly reversed), and both Maine and Nebraska utilize district systems today. That these reforms have not spread to other states has been largely the consequence of partisan politics. Parties that are confident that they can win a majority of the statewide popular vote have generally opposed switching to district or proportional systems because such a change would likely cost their party electoral votes. Nonetheless, both major parties have mounted campaigns to enact such reforms (in different targeted states) in the twenty-first century.

To most Americans today, the most desirable means of reforming the Electoral College would be to abolish the institution and replace it with a national popular vote: the candidate who wins the most votes nationally becomes president. This approach, which requires a constitutional amendment, has the important virtue of conforming with the democratic value that all votes should count equally.[4] This idea was first debated in Congress in 1816 and has long had dedicated advocates. For much of our history, however, a national popular vote was anathema to the states of the South, where African Americans were enslaved until the Civil War and disenfranchised for most of the following century. Under the Electoral College, African Americans counted toward a state’s population and thus electoral votes (as three-fifths of a person until the Civil War and five-fifths thereafter). But, since they were not permitted to cast ballots, they would have no impact in a national popular vote. The South thus stood to lose significant political influence if a national popular vote system were adopted (and Blacks were not enfranchised).

To most Americans today, the most desirable means of reforming the Electoral College would be to abolish the institution and replace it with a national popular vote: the candidate who wins the most votes nationally becomes president. This approach, which requires a constitutional amendment, has the important virtue of conforming with the democratic value that all votes should count equally.[4] This idea was first debated in Congress in 1816 and has long had dedicated advocates. For much of our history, however, a national popular vote was anathema to the states of the South, where African Americans were enslaved until the Civil War and disenfranchised for most of the following century. Under the Electoral College, African Americans counted toward a state’s population and thus electoral votes (as three-fifths of a person until the Civil War and five-fifths thereafter). But, since they were not permitted to cast ballots, they would have no impact in a national popular vote. The South thus stood to lose significant political influence if a national popular vote system were adopted (and Blacks were not enfranchised).

The prospect of a national popular vote replacing the Electoral College gained steam in the 1960s, the same era in which the federal government promoted substantial advances in civil rights in the South. According to public opinion polls, more than two-thirds of the American people favored a direct national election, and, importantly, support was bipartisan. A constitutional amendment to implement a national vote was overwhelmingly approved by the House of Representatives in 1969, but a year later it was blocked in the Senate by a filibuster led by southern senators. The initiative was revived in the 1970s but again failed in the Senate. Since that time, support for this reform has ceased to be bipartisan. Republicans in the 1980s became convinced that the Electoral College was more advantageous to them than a national popular vote would be, and there consequently has been little action in Congress—despite the preferences of most Americans.

The difficulty of mustering super-majorities in Congress for a constitutional amendment, coupled with the shock of a “wrong winner” election in 2000, led to the emergence, in the early twenty-first century, of new ideas for instituting reform without amending the Constitution. The most well known of these, labeled the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, called for individual states to join an agreement that they would cast their electoral votes for the winner of the national (rather than state) popular vote. The compact would take effect only after it had been joined by states with a majority of all electoral votes. Beginning in 2007, seventeen states (plus the District of Columbia) joined the compact, but the prospect of its success had dimmed by the early 2020s, in part because of ongoing Republican opposition and in part because of numerous questions that were raised regarding its legality and durability.

For more than 200 years, many Americans have regarded the Electoral College as a flawed and troublesome method of choosing the nation’s chief executive, as an institution that does not embody the democratic values that are central to the nation’s self-image. That the institution has nonetheless survived owes less to its intrinsic merits than to shifting partisan interests, the challenge of reaching agreement about alternatives, and the sheer difficulty of amending the Constitution. The long track record of defeated reform efforts has surely led many to doubt the possibility of change. In 2001, former President Jimmy Carter predicted that, regrettably, “200 years from now, we will still have the Electoral College.”[5] But new reform efforts have continued to arise, backed by political activists, some office holders, and public opinion. Whether they can finally solve the complex equation of Electoral College reform remains an open question.

Alexander Keyssar is the Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He is the author of The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (Basic Books, 2000) and Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? (Harvard University Press, 2020).

[1] One amendment dealing with the Electoral College—but having little bearing on subsequent reform efforts—was approved by Congress and ratified by the states in 1804. The original Constitution (which did not envision political parties) did not provide for separate candidacies for president and vice president; it mandated that the winner of the most electoral votes would become president and the runner-up would become vice president. By 1800, however, parties did exist, and they were nominating pairs of candidates for the two offices. This lack of fit between the Constitution and political practice led to a crisis in the counting of votes in 1800. To resolve this problem, the Twelfth Amendment provided that there would be separate candidacies for president and vice president.

[2] The other design feature that can yield a “wrong winner” election is the allocation of two electoral votes to each state, regardless of its population. This means that small states receive, and cast, more electoral votes per capita than do large states.

[3] Passage of a constitutional amendment requires a two-thirds vote in each branch of Congress followed by ratification in three-quarters of the states.

[4] An amendment would have to indicate whether a candidate would be obliged to win an outright majority of all votes cast to become president or whether a plurality would be sufficient. The Electoral College requires a winning candidate to receive a majority of all electoral votes. If no candidate does so, the decision reverts to the House of Representatives where each state receives one vote and a majority is required for election. This “contingent election” mechanism has itself been severely criticized and numerous reforms have been proposed, but the mechanism itself has not been utilized since 1824.

[5] Former President Jimmy Carter, comments at the meeting of the National Commission on Federal Election Reform, The Carter Center, Atlanta, March 26, 2001.