Playing by the Rules: Our Remarkably Balanced Electoral College

by Trent England

Politics is full of sports metaphors. Candidates run in election “races.” A great debate performance might be a “knock-out punch,” but a poor answer is a “fumble.” Leading candidates hope to “run out the clock,” while those far behind attempt a “Hail Mary pass.” Political competitions, like sports, are defined by particular “rules of the game.” In American presidential elections, we call these rules the Electoral College.

While a set of rules may change over time, we often can identify when they first were established. For basketball, it was 1891, when James Naismith came up with the original thirteen rules. Baseball’s beginnings are murkier but seem to date back to the New York Knickerbocker Baseball Club in 1845. And while some of the details are lost to history, we do know that the Electoral College was devised in the final days of the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

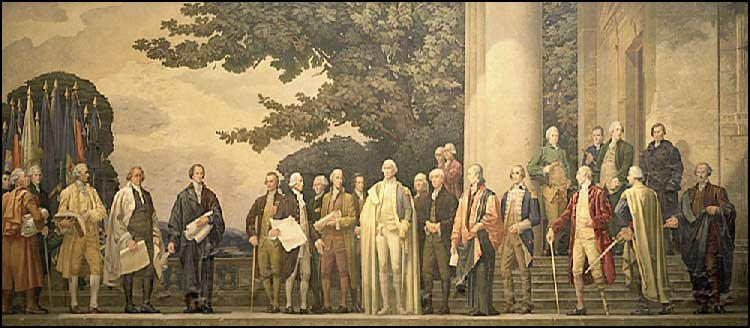

Framing the Constitution

Should we have several presidents—an executive council, perhaps—or just one? The Constitutional Convention quickly arrived at a consensus to have one. That made the election process even more important, and on that there was no consensus. The Virginia Plan proposed that Congress elect the president, but then the legislative branch would control the executive branch. Without a separation of powers, could we really have checks and balances?

Some delegates proposed a direct national vote, but others pointed out that voters would know little about the character of politicians from other states. Delegates from small states in both the South and North were adamantly opposed to a direct election. There were also concerns about demagogues and foreign interference.

James Wilson, a delegate from Pennsylvania, proposed that states elect delegates who would then vote for president. At first, only his own delegation from Pennsylvania and those from neighboring Maryland supported his idea. It languished until near the end, when a committee finally took Wilson’s proposal and wrote it into the beginning of Article II of the Constitution.

James Wilson, a delegate from Pennsylvania, proposed that states elect delegates who would then vote for president. At first, only his own delegation from Pennsylvania and those from neighboring Maryland supported his idea. It languished until near the end, when a committee finally took Wilson’s proposal and wrote it into the beginning of Article II of the Constitution.

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.

These electors were to meet in their own state and cast two votes for president. Whoever gets the most votes wins, provided this is a majority, or else the House of Representatives elects one of the leading candidates. Whoever gets the second-most votes becomes the vice president.

The Twelfth Amendment

Before the Constitution took effect, a common belief was that presidential electors would debate and vote based on each one’s own choice. Such a process was unlikely to produce a majority winner, so presidents would really be chosen by the House of Representatives. In fact, that happened just twice, in 1800 and 1824. Instead, it became common practice for electors to be chosen based on their commitment to support a particular candidate.

Political parties are the natural result of political freedom and competitive elections. Interested people organize to win. And when winning requires majority support for one candidate, political factions tend to band together into two closely matched coalitions—a “two-party system.”

The original Electoral College, however, allowed one party to win the presidency while the other won the vice presidency. This happened in 1796: John Adams became president while his rival, Thomas Jefferson, became vice president. Four years later, Jefferson tied with Aaron Burr, who was supposed to be his vice president but then tried for the top job. Alexander Hamilton eventually convinced a few House members to put Burr in his place (and Burr later shot and killed Hamilton), but the time had come for a constitutional fix.

The Twelfth Amendment says that each presidential elector casts one vote for president and another for vice president. Ratified in 1804, it creates the system we have today, where two candidates run as a “ticket.”

During this same time, state legislatures experimented with different ways of choosing electors. Some simply appointed them, but soon most were holding elections. Some states created presidential elector districts, some used other districts, but many began to hold one statewide election to choose them all. This “winner-takes-all” system maximizes a state’s political voice and is used by forty-eight states and DC today.

Checks & Balances

Since the Twelfth Amendment, the constitutional rules have been remarkably stable. Yet the process has changed as states, parties, and campaigns adapt to these rules in different ways. The Electoral College has also gone from being one of the least controversial parts of the Constitution to a focus of criticism and the subject of more than 700 proposed amendments to reform or eliminate it.

One reason those efforts have failed is the remarkable balance of Electoral College outcomes. The two major parties have each won fifteen of the last thirty presidential elections (1908–2024). In this modern era there is just one period when a party won more than three elections in a row.

Here again, what is true in sports is true in politics. Leagues use player drafts, salary caps, and other rules to promote balance among their teams, seeking to produce better competition and more engagement from players and fans alike. In democratic political systems, voter engagement is higher when voters believe their candidates can win—maybe not today, but at least in a future election.

What explains the Electoral College balance? One reason is that it limits (or checks) how much power any one state can have. Winning an Electoral College majority requires winning a lot of states. As a practical matter, a campaign needs to start with strong support in at least some states. This is why political parties matter—they build and maintain a base of political support that allows campaigns to reach out to “swing” voters and states.

A campaign that begins with a strong base of support in fifteen to twenty states, then wins over moderate voters in more evenly divided states, might just build the kind of national coalition that can win the Electoral College. In fact, both the Democrats and Republicans are working every day to make this possible.

Change the Rules?

Some people still want a change. Many favor a direct, centrally run election. This might have one round with a plurality winner, or two rounds so that the winner has a majority of the final vote (France uses this system). Others want all presidential electors chosen by district, similar to Maine and Nebraska.

A unique proposal is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. It would leave the Electoral College in place, but have states choose presidential electors based on the nationwide popular vote. This could force the Electoral College to align with the popular vote result—as if it was replaced with a direct election (the compact takes effect if passed by states that together have a majority of electoral votes).

John Koza, who created the compact, recognizes that it seems like an “end run” around the Constitution. “When people complain that it’s an end run,” Koza explains, “I just tell them, ‘Hey, an end run is a legal play in football.’”[1]

Any of these rule changes would eliminate at least some checks and balances. A direct, national election could lead to more candidates with narrower support and winners with small pluralities. Parties might fragment, becoming regional factions rather than national coalitions. Koza’s compact, for example, has no runoff or majority requirement, nor does it establish a process for nationwide recounts.

The Electoral College is a uniquely American invention. Its constitutional structure has remained the same for more than two centuries. It favors political parties that are broad, national coalitions. In the modern era, this has produced a competitive political environment with remarkably balanced outcomes.

When Alexander Hamilton wrote about the Electoral College in The Federalist Papers, he said, “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.”[2] Perhaps today he would say, “It’s a home run.”

Trent England is the founder and executive director of Save Our States and the David & Ann Brown Distinguished Fellow at the Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs. He is the author of Why We Must Defend the Electoral College (Encounter Books, 2020) and the producer of the feature-length documentary film Safeguard: An Electoral College Story (2020).

[1] Quoted in Rick Lyman, “Innovator Devises Way Around Electoral College,” New York Times, September 22, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/22/us/politics/22electoral.html.

[2] Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 68, in The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser, March 12, 1788, repr. Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0218.