The Vanishing Role of Presidential Electors

by Robert M. Alexander

In explaining the Electoral College, Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 68 that “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.”[1] Despite Hamilton’s claim, the institution has remained one of the most maligned features of the Constitution with hundreds of proposals to amend or abolish it. Indeed, the institution created by the Framers devolved into a constitutional crisis with the election of 1800 and was quickly changed through the passage of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804. Because of the Twelfth Amendment, the Electoral College we know today is very different from the one conceived by the Framers.

In explaining the Electoral College, Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 68 that “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.”[1] Despite Hamilton’s claim, the institution has remained one of the most maligned features of the Constitution with hundreds of proposals to amend or abolish it. Indeed, the institution created by the Framers devolved into a constitutional crisis with the election of 1800 and was quickly changed through the passage of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804. Because of the Twelfth Amendment, the Electoral College we know today is very different from the one conceived by the Framers.

In Philadelphia in 1787, debate over the selection of the president centered on three prospective models: having Congress choose the president, having state legislatures make the choice, or having a direct popular vote to select the president. The Electoral College emerged late in the Convention through the Committee on Unfinished Parts. Ultimately, the Framers settled on an institution combining parts of all three plans.

States were afforded representation equal to their membership in the Congress. This permitted a balance of sorts between the most populated states (via their House representation), along with equality of all states through their Senate representation. Each state legislature was given autonomy to determine how they would award their electoral votes. Some chose direct election, while others used their state legislatures to appoint presidential electors. Additionally, the Framers entrusted a temporary body of electors to choose who they thought would be best to represent the fledgling country.

In Federalist 68, Hamilton indicated that electors would be “most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to so complicated an investigation.” This was to be a deliberative body with the sole task of selecting our nation’s leaders. It was important to the Framers that electors would favor candidates who would put national interests over regional ones.

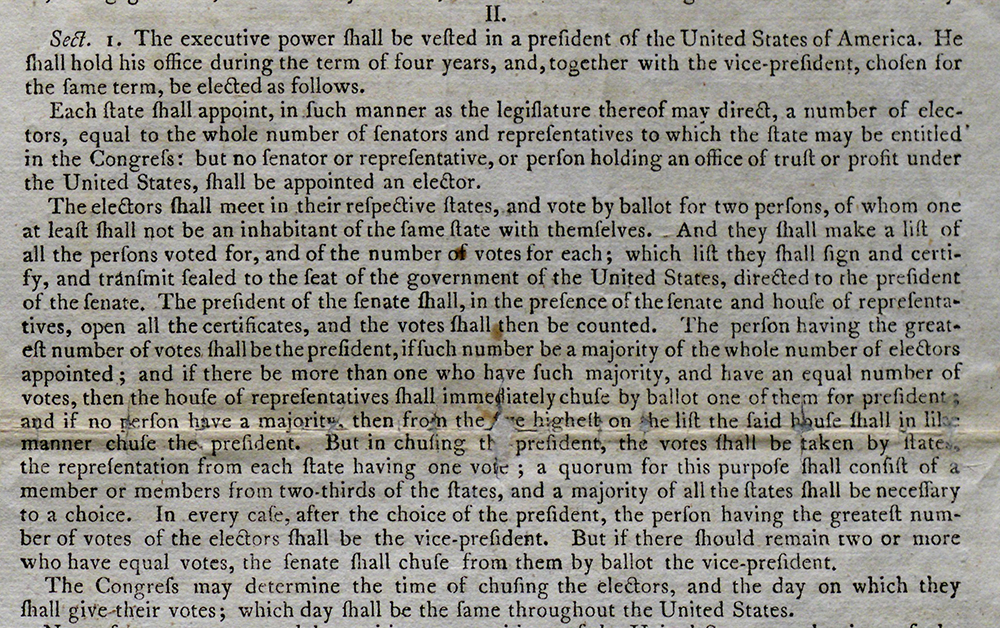

In the original scheme, the top two candidates receiving votes in the Electoral College would become the president and vice president, respectively. Some Framers believed that few candidates would be able to muster a majority of electoral votes and the Electoral College would thus serve as a nominating body where Congress would ultimately select the president. After the tenure of George Washington, however, state parties began soliciting pledges from electors in an attempt to strengthen party control over the process.

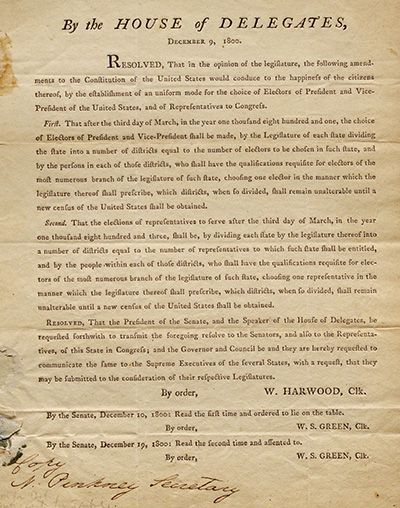

In the election of 1800, electors supporting Thomas Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, cast one vote for each of them respectively, which resulted in a tie. There was no distinction in their votes between president or vice-president and because there was no majority, the result was thrown into the House of Representatives. After thirty-six ballots and much tumult, Jefferson emerged as the victor. This episode led to the quick passage of the Twelfth Amendment. Among other things, it required electors to cast one vote for president and one vote for vice president. This change cemented party control over the presidential selection process.

In the election of 1800, electors supporting Thomas Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, cast one vote for each of them respectively, which resulted in a tie. There was no distinction in their votes between president or vice-president and because there was no majority, the result was thrown into the House of Representatives. After thirty-six ballots and much tumult, Jefferson emerged as the victor. This episode led to the quick passage of the Twelfth Amendment. Among other things, it required electors to cast one vote for president and one vote for vice president. This change cemented party control over the presidential selection process.

The emergence of party tickets transformed the office of elector from one of independence to one of obedience. Electors would now be chosen for their fidelity to party, rather than their discretion. Yet, while the expectation was that electors would be loyal to their party ticket, the reality was that the Twelfth Amendment did not require electors to vote in accordance with their party’s wishes.

The Constitution leaves the question as to how electors would be chosen up to state legislatures. Early on, some states used direct election of electors and others had their state legislatures choose them. By 1816, nine states used state legislative selection and ten used a direct popular vote.[2] However, by 1836, all states but South Carolina opted to select their electors through a popular vote. The move to have electors popularly elected aligns with a push toward a more democratized institution.

Today, all electors are popularly elected in all states. The notion of state legislatures choosing electors on behalf of a state would be met with great resistance. Likewise, electors who use their own discretion, rather than following the will of their state, have earned the ignominious label of being “faithless electors.” Neither practice is required by the Constitution, but are decisions left to the states. While a state legislature has not appointed electors since Colorado gained statehood in 1876, faithless electors have occurred, especially over the last century.

The first instance of a faithless elector occurred in the election of 1796 when Samuel Miles voted for Thomas Jefferson over his fellow Federalist John Adams. In reference to Miles, another Federalist exclaimed: “I chuse him to act, not to think.”[3] There have been 165 faithless votes in history, with many different reasons behind each of them.[4] There were sixty-three in 1872 due to the death of their presidential candidate, Horace Greeley. In 1836, twenty-three Virginia electors refused to vote for the vice-presidential candidate, Richard Mentor Johnson, over his relationship with a Black woman. This prevented him from earning a majority of electoral votes, forcing a contingent election in the Senate where Johnson ultimately was selected.

After a long hiatus, faithless voting reemerged in the 1948 election when a Tennessee elector voted for Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond over the Democratic nominee, Harry S. Truman.[5] Faithless electors have occurred in ten of the last twenty presidential elections. This includes a West Virginia Democrat in 1988 who upon learning that she could vote however she wished, chose to switch the ticket around by voting for Lloyd Bentsen as president and Michael Dukakis as vice president in an attempt to draw attention to the issue of faithless votes.[6] An Al Gore elector from the District of Columbia chose to abstain in the razor-thin 2000 election in an effort to protest the lack of voting rights in the District.[7]

In 2004, a Minnesota elector mistakenly voted for vice-presidential nominee John Edwards twice—once for vice president and once for president. On the presidential ballot the elector spelled Edwards’s name as Ewards.[8] The vote occurred in private and no elector took responsibility for it. The state promptly passed a law requiring electors’ votes to be cast in public and treated any rogue votes as a resignation of the office, where the vote would be vacated, and the elector would be immediately replaced. This same law would be put to the test a few years later when a record number of faithless votes were cast in the 2016 election including that of an elector in Minnesota who was replaced after his faithless vote.

Prior to the 2016 election, several Republican electors indicated that they would not be able to vote for Donald Trump if he were to win their state.[9] Several of these electors either resigned or were replaced prior to the election. In the wake of the election, the so-called “Hamilton elector” movement emerged in an attempt to block Trump from assuming the presidency.[10] This group lobbied fellow electors to vote for a consensus candidate in an effort to deny any candidate a majority and to encourage the House of Representatives to choose a more moderate leader. As a result, a record number of electors sought to cast faithless votes (ten), with seven being successful.

The state of Washington had criminalized faithless votes after the state witnessed a rogue elector in the 1976 election. As a result, four faithless electors from Washington challenged the law relying on Hamilton’s position in Federalist 68, arguing that the original role of electors was to use their discretion to make wise decisions in the best interest of the country. To that point, every faithless vote had been counted by Congress and no federal statute prohibited the act. Prior to the 2020 election, the Supreme Court heard the arguments from the rogue electors in Chiafalo v. Washington.

The Court unanimously sided with the states, agreeing that they have the power to bind and punish faithless electors. Many observers considered the ruling would eliminate the possibility of future faithless electors. However, thirteen states currently have no laws prohibiting faithless votes and fifteen more states have no means to cancel rogue votes if they are cast, which would create great uncertainty around the constitutionality of those votes.[11]

The Electoral College has remained incredibly resilient in the face of much criticism. Almost immediately, the institution changed considerably with the passage of the Twelfth Amendment. Political parties have been the gatekeepers of the Electoral College and presidential electors are an historical artifact of the original body. Although they are seldom noticed, they continue to have a vital role in the presidential selection process. While steps have been taken to curtail their independence, the fact remains that though elector independence has nearly disappeared, it has not vanished altogether.

References

Alexander, Robert M. Presidential Electors and the Electoral College: An Examination of Lobbying, Wavering Electors, and Campaigns for Faithless Votes. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2012.

Alexander, Robert M. Representation and the Electoral College. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Cheney, Kyle. “The Rogue Electors’ Long Game.” Politico. December 19, 2016, https://www.politico.com/story/2016/12/electoral-college-rogue-electors….

Gihring, Tim. “The Enduring Mystery of America’s Last ‘Faithless Elector.’” MinnPost. December 15, 2016. https://www.minnpost.com/politics-policy/2016/12/enduring-mystery-america-s-last-faithless-elector/.

Hamilton, Alexander, et al. The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed Upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes. New York, NY: J. and A. McLean, 1788.

Peirce, Neal R., and Lawrence D. Longley. The People’s President: The Electoral College in American History and the Direct Vote Alternative. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981.

“Presidential Elections.” FairVote. October 2024. https://fairvote.org/resources/presidential-elections/.

Robert M. Alexander is founding director of the Democracy and Public Policy Research Network (DePo) at Bowling Green State University. Formerly the Wilfred E. Binkley Endowed Professor of Political Science at Ohio Northern University, he is the author of Representation and the Electoral College (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[1] Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 68, in The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser, March 12, 1788, repr. Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0218.

[2] Robert M. Alexander, Representation and the Electoral College (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 58.

[3] Quoted in Neal R. Peirce and Lawrence D. Longley. The People’s President: The Electoral College in American History and the Direct Vote Alternative (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), 36.

[4] See “Presidential Elections,” FairVote (October 2024), https://fairvote.org/resources/presidential-elections/.

[5] Robert M. Alexander, Presidential Electors and the Electoral College: An Examination of Lobbying, Wavering Electors, and Campaigns for Faithless Votes (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2012), 45.

[6] Alexander, Presidential Electors, 45.

[7] Alexander, Presidential Electors, 45.

[8] Tim Gihring, “The Enduring Mystery of America’s Last ‘Faithless Elector,’” MinnPost (December 15, 2016), https://www.minnpost.com/politics-policy/2016/12/enduring-mystery-america-s-last-faithless-elector/.

[9] Alexander, Presidential Electors, 156–157.

[10] Kyle Cheney, “The Rogue Electors’ Long Game,” Politico (December 19, 2016), https://www.politico.com/story/2016/12/electoral-college-rogue-electors….

[11] See “Presidential Elections,” FairVote (October 2024), https://fairvote.org/resources/presidential-elections/.