Exploring the Electoral College Universe

by Eric Burin

The Electoral College is a vast and bountiful area of study. A host of historians, legal scholars, and political scientists, as well as practitioners of other disciplines, have examined it and their investigations have not infrequently resulted in noticeably large publications.[1] Even so, we have explored just a fraction of the Electoral College universe.

What follows are four suggestions for future research.

The Constitutional Convention (1787)

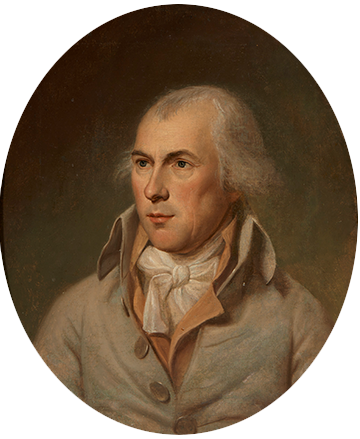

At the Constitutional Convention, the question of how the “national executive” (i.e., the president) would be “appointed” (i.e., elected) engendered three months of intense, high-stakes problem solving that culminated in the adoption of what became known as the Electoral College. That gripping story may be best told by the delegates themselves. The account left by Virginia delegate James Madison in his famous Notes is especially robust, and it can be found in its entirety in the Resources section of the expanded and revised edition of the open-access anthology Picking the President: Understanding the Electoral College (2025).[2]

At the Constitutional Convention, the question of how the “national executive” (i.e., the president) would be “appointed” (i.e., elected) engendered three months of intense, high-stakes problem solving that culminated in the adoption of what became known as the Electoral College. That gripping story may be best told by the delegates themselves. The account left by Virginia delegate James Madison in his famous Notes is especially robust, and it can be found in its entirety in the Resources section of the expanded and revised edition of the open-access anthology Picking the President: Understanding the Electoral College (2025).[2]

While taking in the larger tale of the Electoral College’s creation and adoption, it may be worthwhile to track how and why it came to include the clause that provides that “Each State shall appoint” their respective electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” As Madison’s Notes reveal, the convention initially passed a legislative system for the national executive’s appointment (i.e., the national legislature would pick the president). However, ongoing disputes over that system led to the adoption and development of an elector system in which state legislatures would select electors, who in turn would pick the president. The convention subsequently abandoned that elector system and re-adopted a legislative system. Yet the latter never became a fully formed, politically viable plan. Moreover, all the while, some delegates championed “the people’s” participation in the national executive’s appointment. Thus, late in the convention, with the matter still unsettled, it was assigned to an eleven-member Committee on Postponed Parts.[3]

Consider the problem from the perspective of the delegates who favored the people’s participation in the national executive’s appointment (among them was Madison, who served on the Committee on Postponed Parts and evidently took the lead in designing the system that appeared in its report and eventually was adopted by the convention). To many such delegates, a legislative system was the most objectionable. An elector system in which state legislatures selected electors was better, but far from optimal. Since those bodies alone would appoint electors, the people would be excluded from the process. There was at best a very slim chance of passing an elector system in which states were required to hold popular elections for electors, and by then there was virtually no chance of instituting a nationwide popular vote system. Consequently, to foster the people’s participation in the national executive’s appointment, the committee’s report expanded state legislatures’ authority over the appointment of electors. The clause that provides that “Each state shall appoint” their respective electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct” was crafted to permit those bodies to hold popular elections for electors. Perhaps the clause’s proponents (and opponents) foresaw that conducting such contests in one state would make it difficult to deny them in others. By the time Madison died in 1836, all but one state held popular elections for electors. Seen this way, the clause worked as intended.[4]

Ratification of the US Constitution (1787‒1788)

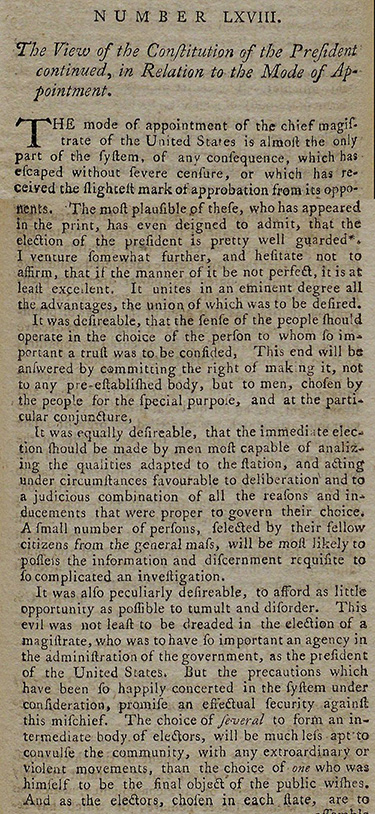

The Constitution set the terms for its own ratification. Ultimately, it needed to be approved by nine state ratifying conventions, the delegates to those conventions being popularly elected.[5] Viewed bi-focally, with one eye on the past and the other on the present, one is struck by the contrast between, on one hand, the richness of the Electoral College’s role in the ratification contest, and, on the other hand, modern-day commentators’ singular focus on just one part of one sentence of one document: Alexander Hamilton’s claim in Federalist No. 68 that, regarding the prospective constitution’s process for picking the president, “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.”[6] In the spirit of problem solving, we can use the inordinate attention accorded to that snippet of Federalist No. 68 to our advantage.[7] The renown of Hamilton’s quip makes it well-suited to serve as a starting point for a wider-ranging survey of the topic (one which could include an examination of Hamilton’s many other words and deeds regarding the national executive’s appointment).[8] Put another way, the pervasiveness of Hamilton’s thirteen-word assertion can be leveraged to promote a more fulsome understanding of the Electoral College.

The Constitution set the terms for its own ratification. Ultimately, it needed to be approved by nine state ratifying conventions, the delegates to those conventions being popularly elected.[5] Viewed bi-focally, with one eye on the past and the other on the present, one is struck by the contrast between, on one hand, the richness of the Electoral College’s role in the ratification contest, and, on the other hand, modern-day commentators’ singular focus on just one part of one sentence of one document: Alexander Hamilton’s claim in Federalist No. 68 that, regarding the prospective constitution’s process for picking the president, “if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.”[6] In the spirit of problem solving, we can use the inordinate attention accorded to that snippet of Federalist No. 68 to our advantage.[7] The renown of Hamilton’s quip makes it well-suited to serve as a starting point for a wider-ranging survey of the topic (one which could include an examination of Hamilton’s many other words and deeds regarding the national executive’s appointment).[8] Put another way, the pervasiveness of Hamilton’s thirteen-word assertion can be leveraged to promote a more fulsome understanding of the Electoral College.

The National Popular Vote Compact (2006‒ )

If Hamilton’s line from Federalist No. 68 unduly shapes our perception of the Electoral College, the opposite may be true of the National Popular Vote Compact (NPVC), a binding agreement between states that, if put into operation, effectively would result in a nationwide popular vote.[9]

Publicly initiated at a press conference in February 2006, the NPVC movement has had an extensive run, especially for a cause that concerns the Electoral College. Moreover, the enterprise has been unusually successful; the NPVC has been adopted by eighteen jurisdictions (specifically, seventeen states and the District of Columbia). These eighteen jurisdictions currently control 209 electoral votes.[10] Thus, to become operational, the NPVC needs to secure sixty-one more electoral votes and (assuming it is subject to a legal challenge) the approval of five US Supreme Court justices. By these means, the NVPC campaign arguably has brought the nation as close as it has been to a popular vote since July 25, 1787 (when by one vote the convention rejected a motion to consider a popular vote system in which individuals would have voted for multiple persons across multiple states, an arrangement that aimed to foster nationalism, majoritarianism, and the chances that a small-state resident would be elected president).[11] Whatever one makes of the NPVC, as a topic of study, it is historically significant in its own right.

The Electoral College in the American Mind Dataset (2024)

A fourth topic ripe for investigation is The Electoral College in the American Mind Dataset. The dataset was generated by a national study that I oversaw in September 2024, the purpose of which was to better understand people’s thoughts and feelings about the Electoral College. Administered to 1,500 adults in the United States and weighted to the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey demographic targets, the study’s survey instrument was a questionnaire that posed thirty Electoral College–themed questions. Twenty-eight of the questions were written in a multiple-choice format, and two were written in an open-ended format. The dataset consists of the aggregate responses to the former, cross-tabulated by the respondents’ demographic characteristics. It and the questionnaire are available in an open-access format on the University of North Dakota Scholarly Commons.[12]

Up close, the Constitutional Convention, ratification contest, NPVC, and The Electoral College in the American Mind Dataset are sizable topics, but viewed from afar, they are mere specks in the Electoral College universe. The opportunities for inquiry, in other words, are practically limitless and, given the nature of the subject, the stakes hardly could be higher.

Eric Burin is professor of history at the University of North Dakota, author of Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society (University Press of Florida, 2005), and editor of the open-access anthologies Protesting on Bended Knee: Race, Dissent, and Patriotism in 21st Century America (2018) and Picking the President: Understanding the Electoral College (revised and expanded edition, 2025), both published by the Digital Press at the University of North Dakota.

[1] Alexander Keyssar, Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020); John R. Koza, Barry Fadem, Mark Grueskin, Michael S. Mandell, Robert Richie, and Joseph S. Zimmerman, Every Vote Equal: A State-Based Plan for Electing the President by National Popular Vote, 5th edition, 2nd printing (Los Altos, CA: National Popular Vote Press, 2024), https://www.every-vote-equal.com/sites/default/files/Every-Vote-Equal-5th-Ed-2nd-Printing-Oct-2024.pdf; Eric Burin, ed., Picking the President: Understanding the Electoral College, expanded and revised edition (Grand Forks, ND: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota, 2025), https://thedigitalpress.org/Picking-the-President-2/.

[2] Resources 1‒26 consist of Madison’s Notes for the twenty-six days of debate on the issue at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Burin, ed., Picking the President, 219‒329. See also pp. 79‒80 and 217.

[3] Burin, ed., Picking the President, 232, 238, 239, 250, 260, 261‒265, 267, 270, 282, 287, 289, 293‒294, 295, 296, and 297. See also pp. 81‒86.

[4] Burin, ed., Picking the President, 87, 299, 307‒308, 316. See also pp. 88‒91.

[5] The Resources section of Picking the President features seventeen items that collectively provide a sweeping outlook on the ratification of the US Constitution. Burin, ed., Picking the President, 341‒388. See also pp. 91‒93. Additionally, see “Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution,” Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://csac.history.wisc.edu/publications-2/dhrc/.

[6] Jonathan Sickler, “Testimony in Support of SCR 4013,” [North Dakota] Senate State and Local Government Committee, February 21, 2025, https://ndlegis.gov/assembly/69-2025/testimony/SSLG-4013-20250221-38295-F-SICKLER_JONATHAN.pdf.

[7] Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 68, in The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser, March 12, 1788, repr. Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0218.

[8] To cite one example, in January 1789 (i.e., ten and a half months after the publication of Federalist No. 68), Hamilton identified to James Wilson, who at the Constitutional Convention had been the first to suggest a popular vote to pick the president and, one day later, the first to propose an elector system for that purpose, the “defect” in the presidential election system about which “Every body” was aware and had reason “to fear” (i.e., the provision that presidential electors “shall . . . vote by ballot for two persons, of whom one at least shall not be an inhabitant of the same State with themselves”). Hamilton observed that the provision rendered it “possible that the man intended for Vice President may in fact turn up President.” Consequently, he warned, it could be exploited by the new government’s foes to deny George Washington victory in the nation’s first presidential election. To thwart such threats, Hamilton urged the exploitation of the same provision. “From Alexander Hamilton to James Wilson, [25 January 1789],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-05-02-0075. For Hamilton’s expressions regarding the national executive’s appointment at the Constitutional Convention, see Burin, ed., Picking the President, 243‒246 and 315‒316. For Wilson’s initial suggestion and subsequent proposal, see Burin, ed., Picking the President, 228‒229 and 231. The provision of which Hamilton wrote was altered in 1804 by the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, which provides that electors, instead of casting two ballots for president, “shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President,” the differentiation between the offices being termed “designation.” Burin, ed., Picking the President, 395‒396.

[9] “Text of the National Popular Vote Compact Bill,” National Popular Vote, https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/bill-text.

[10] “News History,” National Popular Vote, https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/news-history.

[11] Burin, ed., Picking the President, 282. See also pp. 247‒250 and 293‒294.

[12] Eric Burin, “The Electoral College in the American Mind Dataset, September 13‒17, 2024” (2025), Datasets, 32, https://commons.und.edu/data/32. The questionnaire can be found as well in Burin, ed., Picking the President, 97‒107. See also Eric Burin, “The Past, Present and Future of the Electoral College,” North Dakota Monitor, October 24, 2024, https://northdakotamonitor.com/2024/10/31/the-past-present-and-future-of-the-electoral-college/.