The Principle of One Person, One Vote

by Jack Rakove

Americans who think they have a constitutional right to vote for president are mistaken. The power to decide how presidents are elected belongs to the state legislatures. Should they wish to choose their state’s electors themselves, they are free to do so. Or if they wished to make the popular vote advisory only, reserving the final decision for themselves, that could be feasible, too—though they would have to act quickly once Election Day arrived.

Americans who think they have a constitutional right to vote for president are mistaken. The power to decide how presidents are elected belongs to the state legislatures. Should they wish to choose their state’s electors themselves, they are free to do so. Or if they wished to make the popular vote advisory only, reserving the final decision for themselves, that could be feasible, too—though they would have to act quickly once Election Day arrived.

But speculative scenarios like these do not explain why majorities of Americans repeatedly favor abandoning the Electoral College system. Other reasons matter more. Voters never know who the electors are. Those who live in non-battleground states resent being treated as second-class voters whose financial contributions are welcome, but whose political desires and commitments count for nought. Most importantly, many of us believe that in our one truly national election, the vote of every citizen should have the same weight wherever it is cast, which can never be the case with the current system.

Yet before we disparage the Electoral College system as an anachronism from a distant era, it would be better to ask why the Framers of the Constitution adopted it in the first place. The story is more complicated than one might expect. It would be wrong to say that they intended to give the decision to an elite corps of citizens simply because they feared a popular democratic vote. The fact is, the presidency was the most novel institution they created, and its design posed problems they were still wrestling with even as they were preparing to adjourn in September 1787. It helps to understand those problems first.

Three options for presidential election were available in 1787. The most obvious was appointment by Congress. The most problematic was a popular election in a single national constituency, where the states as such would be irrelevant. The most unlikely alternative was the system of presidential electors we wound up with. This last option prevailed not because it was the most attractive but because it was the least unattractive.

Popular election was the first to fail. The initial objection was that it would disadvantage the southern states because their hundreds of thousands of enslaved people had no civic existence of any kind. But the real problem was that the Framers worried that popular elections would often prove indecisive. Voters would simply be too ill-informed and parochial to identify truly national “characters” whose appeal would span state lines.

An election by Congress would solve this problem: who could be better informed than its members? But here other objections intervened. The Framers wanted to make the executive politically independent of Congress. But a president elected by Congress could serve only a single term, because the incumbent would otherwise truckle to dominant congressional factions. Equally importantly, many Framers thought that the promise of reelection would give incumbents a powerful incentive for statesmanlike behavior. That provided the strongest argument against congressional appointment.

The presidential elector system thus became the default option. Here, too, there were qualms. No one had any clear idea who the electors would be. As one delegate grumbled, the electors were unlikely to “be men of the first nor even of the second grade in the States.”[1] The Framers could also have made the choice of electors more democratic, by pairing their election with those for the House of Representatives or by having a proportional statewide vote. They instead left these decisions to the legislatures, with potentially mischievous results. In the hotly contested election of 1800, the three most populous states (Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts) all altered their electoral rules out of rank political calculation.

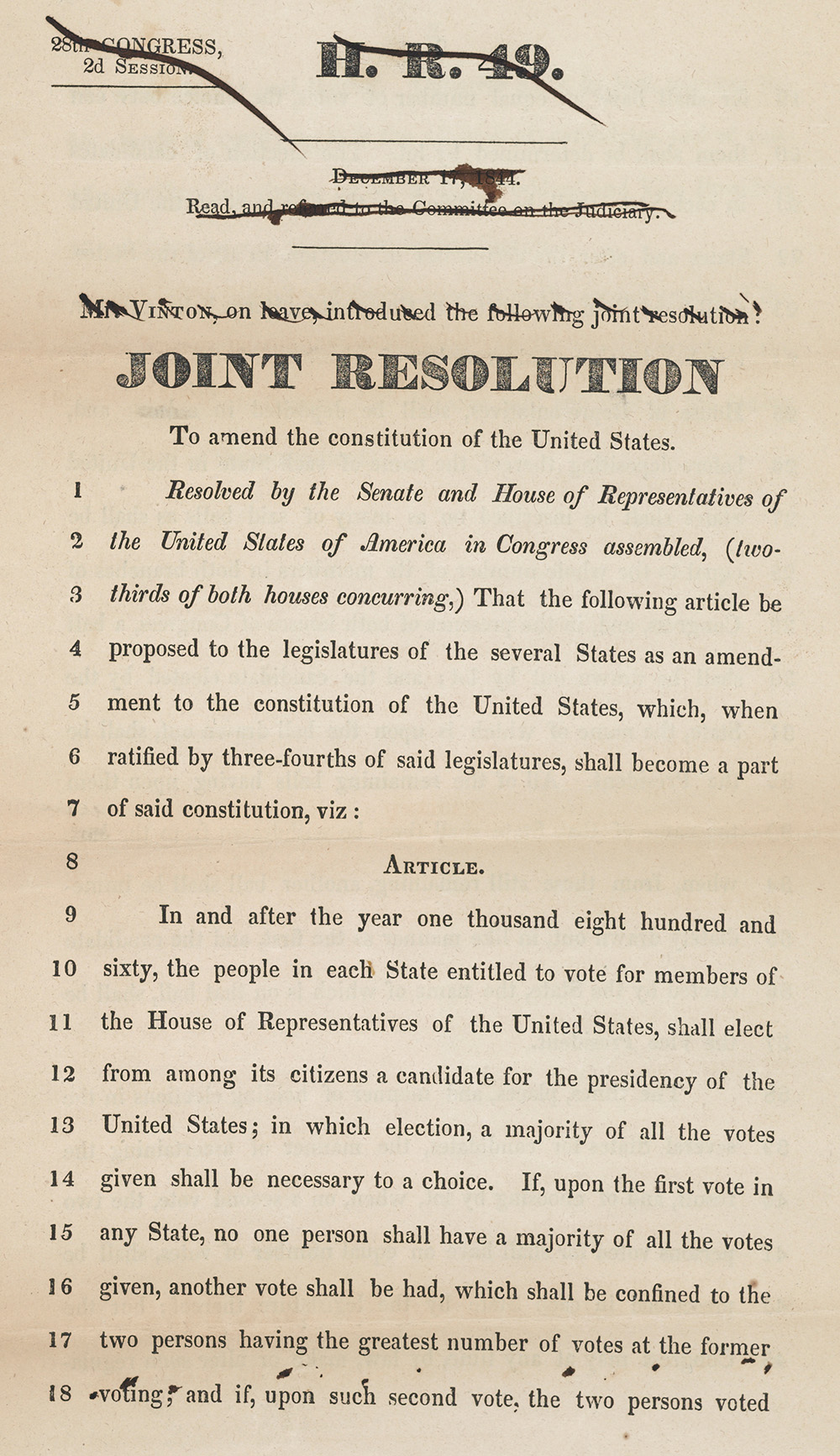

This is the deep historical background to our current discontents. The question remains: What, if anything, can be done to resolve our impasse? The most obvious response would be to adopt a constitutional amendment to attain a National Popular Vote (NPV). The most enticing way to do this involves something called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC). Under its terms, states collectively casting the 270 votes required to elect a president will commit all their votes to the candidate winning the national popular vote, wholly independent of the results within their own states.

As was the case in making sense of the decisions of 1787, it helps to consider the objections against these rival proposals.

As was the case in making sense of the decisions of 1787, it helps to consider the objections against these rival proposals.

Every reader of this essay already knows the case against a formal amendment to the Constitution. It rests on the simple belief that the formal amendment process as established in Article V of the US Constitution has gone the way of the dodo. That belief ignores the historical fact that an NPV amendment seemed close to success a half century ago, passing the House relatively easily, but then dying in the Senate, not because members from the small states blocked it, but because segregationist southern senators worried that the NPV would enhance African American political influence.

The NPVIC is a seemingly clever device to circumvent the daunting rules of the Article V amendment process. If it proves workable in one or two elections, its proponents believe, skepticism about it will quickly fade, and a de facto (though always unstable) amendment of the Constitution will have occurred.

Alas, hopeful reader, there are two objections to this Rube Goldberg model of constitutional change.

First, none of its proponents has ever satisfactorily explained how the NPVIC escapes Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution, which makes interstate compacts subject to the approval of Congress. They argue that the Supreme Court has made it much easier for interstate agreements to escape congressional scrutiny. But those precedents would prove wholly irrelevant to a measure that involves the election of our one truly national official. Some members of Congress would inevitably insist that the NPVIC must be subject to their scrutiny. Once they make that point, it is difficult to imagine how Article V could be evaded.

The second objection reinforces this point by supposing that the NPVIC would be subject to numerous legal challenges filed by voters within the participating states. Couple this litigation with contentious debate within Congress, and any ensuing presidential election would be dogged with enormous controversy about its legitimacy. That is a situation the contemporary United States cannot possibly afford.

There is therefore no alternative to Article V amendment. The true challenge is to strategize how the necessary amendment could be attained.

Part of that campaign would involve disproving one of the great myths that percolate through public opinion: that voters in small states have interests that are qualitatively different from voters in large states. Just pick any interest that matters to you—abortion, gun regulation, foreign policy, health insurance—and ask whether or how the size of the populace of your state affects your interests. None of us ever votes on this basis. The interests and preferences that drive our politics are shared unevenly across all the states. The great fallacy of our presidential election system is that the “senatorial bump” giving each state two electors wrongly makes size itself an interest that needs protection.

I stand by a different principle. Each individual voter possesses an equal interest in the issues that matter most to us, which is why the principle of one person, one vote should cover presidential elections, as it does all others.

Jack N. Rakove is Coe Professor of History and American Studies and Professor of Political Science, Emeritus, at Stanford University. He is the author of Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (Knopf, 1996) and Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).

[1] Hugh Williamson, delegate from North Carolina, on the election of the executive, debates at the Federal Convention, Tuesday, July 24, 1787, in The Anti-Federalist Papers and the Constitutional Convention Debates, ed. Ralph Ketcham (New York: Signet Classics, 1986, repr. 2003), p. 118.