by Steven Mintz

Historical Context: Black Soldiers in the Civil War

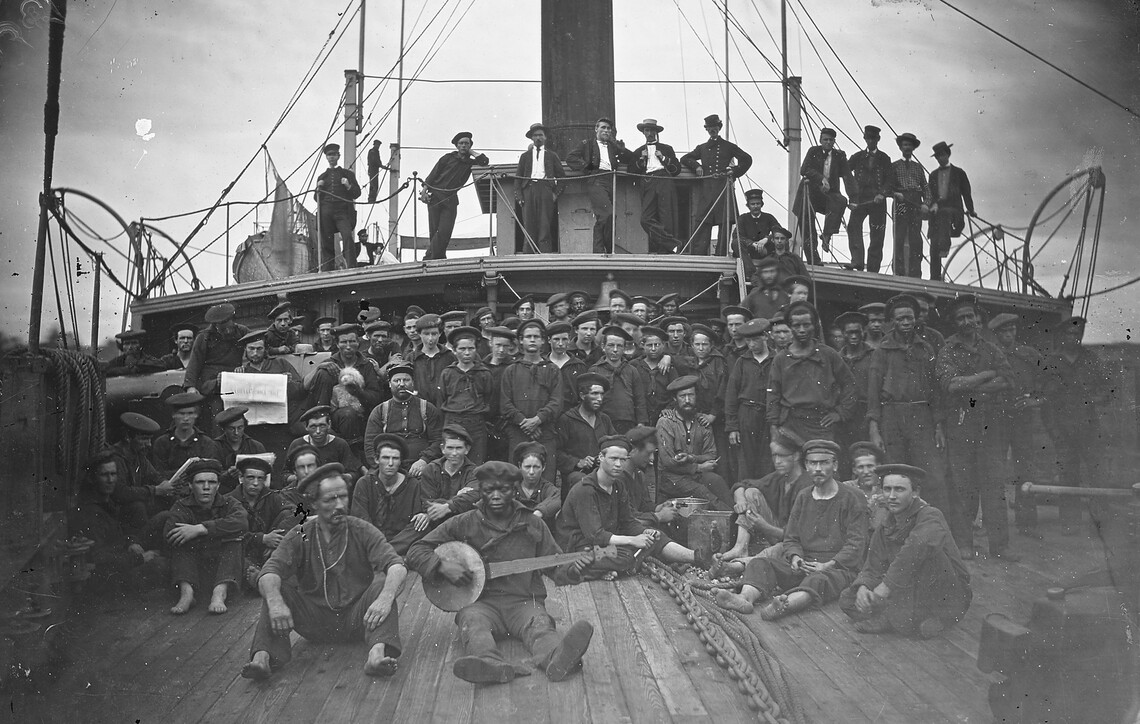

During the Civil War, voluntary enlistments in the Union Army had fallen by early 1863. The federal government’s plan to combat this problem was twofold: institute a military draft and enlist Black soldiers. The latter strategy would build on the US Navy’s ongoing recruitment of Black sailors, state militias’ recruitment of self-emancipated men, and military policies that gave wages to employed Black refugees.

For their part, African American men had already petitioned for the opportunity to enlist. In 1861 William A. Jones of Oberlin, Ohio, had written to the secretary of war to affirm that

“very many of the colored citizens of Ohio and other states have had a great desire to assist the government in putting down this injurious rebellion.” Jones further noted that “we are partly drilled and would wish to enter active service immediately.”

The Black men seeking an opportunity to enlist supported the Union, an end to slavery, and the postwar expansion of civil rights; military service would help them advance all of these interests.

Black soldiers’ and sailors’ enlistment allowed President Lincoln to resist demands for a negotiated peace that might have included the retention of slavery in the United States. Altogether, around 180,000 Black soldiers served in the Union Army and around 18,000 Black sailors served in the Navy. Black soldiers accounted for nearly 10 percent of all Union forces and around 40 percent of the Union dead or missing. Twenty-four Black soldiers and sailors were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor during their generation’s lifetime for their extraordinary bravery in battle, and one additional soldier, Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 2001.

Sixty percent of the Black men who joined the military had once been enslaved. This fact illuminates the meaning of one threat made by the Confederate Congress in 1863: captured Black soldiers would not be treated as prisoners of war. Upon learning of the Confederate Congress’s resolution to enslave Black soldiers captured in battle,

Abraham Lincoln responded with a Retaliation Order: “for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and received the treatment due to a prisoner of war.”

The most widely reported example of Black troops’ bravery occurred in July 1863, when the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first Black regiment raised in the North, led an assault against Fort Wagner, which guarded Charleston, South Carolina’s harbor. Two of Frederick Douglass’s sons, Charles Remond Douglass and Lewis Henry Douglass, were members of this regiment. The New York Daily Tribune reported that the 54th “pressed on through this storm of shot and shell, and faltered not, but cheered and shouted as they advanced.” Over forty percent of the regiment’s members were killed or wounded in the unsuccessful attack.

During the war, African American troops also faced a different kind of battle: a battle against discrimination in pay, promotions, and medical care. Despite promises of equal treatment, African American soldiers were segregated in regiments commanded by White officers; Black sailors served in integrated units. Black soldiers protested and appealed to President Lincoln when Congress initially awarded them less pay than White soldiers as well as inferior benefits and poorer quality food and equipment.

Corporal James Henry Gooding, for example, reminded Lincoln that “we have done a Soldier’s duty” and then asked, “Why can’t we have a Soldier’s pay?”

African American soldiers finally won their fight for equal pay in 1864. In 1865 they became eligible to serve as line officers. For both soldiers and sailors, fair promotion practices would be the next step in securing equal treatment within the military.

Black soldiers’ and sailors’ participation in the Civil War challenged White northerners to reverse racist assumptions. As one Union captain explained, “A great many [White people] . . . have the idea that the entire Negro race are vastly their inferiors. A few weeks of calm unprejudiced life here would disabuse them, I think. I have a more elevated opinion of their abilities than I ever had before. I know that many of them are vastly the superiors of those . . . who would condemn them to a life of brutal degradation.”

Drawing upon the education and training they received in the military, many former soldiers and sailors became community leaders during Reconstruction. One example is Hiram Revels. Revels had helped raise two Black regiments for the Civil War, and he served as a military chaplain for troops who fought at the Battle of Vicksburg in Mississippi. After the war, Revels opened a school for freedpeople and ministered to several congregations. He was elected or appointed to a series of political offices: alderman, state senator, and member of Congress.

Questions for Discussion

Making Observations

- Compare and contrast the photos of Hubbard Pryor before and after he enlisted in the Union Army. How did his attire and posture change? What new possessions did he have after enlistment?

- During the Civil War, previously enslaved people like Private Hubbard Pryor made the case that they were entitled to US citizenship. What in this photo supported their cause?

Drawing Connections

- About 180,000 Black soldiers served in the US military during the Civil War. Using what you see in the photographs and what you read in the essay, create a list of challenges that soldiers like Private Hubbard Pryor faced. Then create a list of new opportunities.

- How do these photographs of one person help you to better understand the larger story of Black people’s military experience? What new questions do they raise? How could you find out the answers to those questions?

Black Civil War soldier Hubbard Pryor before (left) and after (right) enlisting in the 44th US Colored Troops, 1864. (National Archives) View a large JPG of the above image