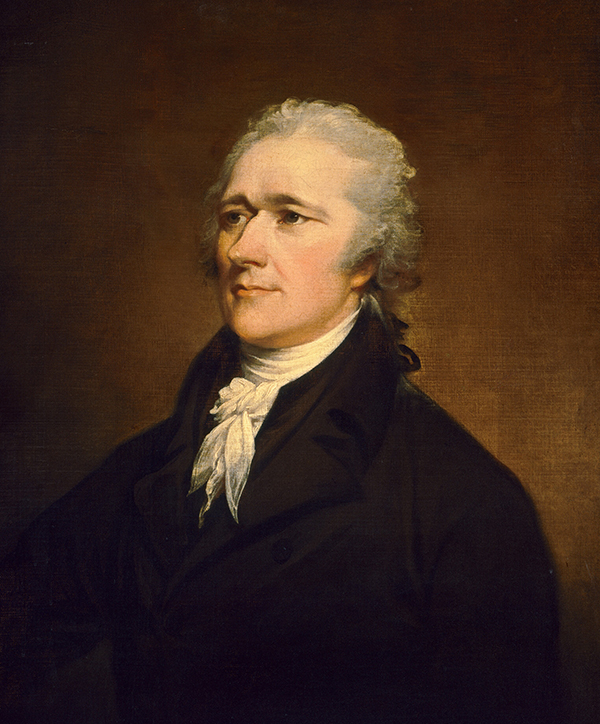

Alexander Hamilton and the US Financial Revolution

by Richard Sylla

While serving as the nation’s first secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795, Alexander Hamilton made two fundamental contributions toward making the US economy the world’s largest and richest roughly a century later, a position it has continued to hold into the twenty-first century.

While serving as the nation’s first secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795, Alexander Hamilton made two fundamental contributions toward making the US economy the world’s largest and richest roughly a century later, a position it has continued to hold into the twenty-first century.

One was his launching of a modern US financial system, a veritable financial revolution (as discussed below). From Hamilton’s time to our own, the system financed our governments in times of war and peace. And it financed our entrepreneurial economy as it transitioned from a focus mostly on agriculture to one focused on industrialization and modern manufacturing, and since the middle of the twentieth century to an economy in which services, including financial services, rather than goods make up most of what our economy produces.

Hamilton’s second important contribution, at a time when most people considered agriculture to be America’s comparative economic advantage, was to espouse manufacturing and economic diversification as waves of the future, and to call upon the government to assist the growth of modern manufacturing to achieve what economists call economies of scale.

How did Hamilton become America’s foremost economic modernizer in the nation’s founding era? It all began with his service as an officer in the Continental Army and General George Washington’s principal aide-de-camp during the War of Independence. As the war dragged on for seven long years, Hamilton struggled to understand why the army was so poorly supplied, and why both the economy and military efforts suffered from a hyperinflation that made the paper money issued by Congress to finance the war virtually worthless.

During lulls in the fighting, of which there were many, Hamilton studied economic and financial history. He discovered that the Dutch Republic and Great Britain had become the richest and most powerful nation-state economies by having financial revolutions early in their modern histories.

During lulls in the fighting, of which there were many, Hamilton studied economic and financial history. He discovered that the Dutch Republic and Great Britain had become the richest and most powerful nation-state economies by having financial revolutions early in their modern histories.

The Dutch financial revolution occurred at the start of the seventeenth century. It made it possible for the republic both to win its independence from mighty Spain and to have its mid-seventeenth-century Golden Age, which one historian has called an “embarrassment of riches.”[1]

Britain’s financial revolution began after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and continued into the early decades of the eighteenth century. It enabled Britain to have the first industrial revolution after 1750, to become the world’s dominant imperial and military power, and—as Hamilton saw it—to threaten US independence.

Hamilton concluded from his early studies that getting America’s deranged finances in order was more important than winning military battles. To do that required reform of the weak government under the Articles of Confederation. As early as 1780, he called for a convention of the states to come up with a plan for stronger, more effective US government. During the 1780s, he and others pushed hard for this idea, which ultimately led to the Philadelphia convention of states in 1787, the US Constitution, and its adoption in 1788. To promote adoption, Hamilton organized a series of eighty-five newspaper essays known to us as the Federalist Papers, and he wrote the majority of them.

George Washington, our first president under the Constitution, appointed Hamilton to be the first secretary of the treasury shortly after Congress in 1789 created that department. Hamilton immediately began to implement a US financial revolution he had been planning for a decade.

What is a financial revolution? And how did Hamilton execute one? Economic and financial historians define such a revolution as the creation in a short period of time of several key institutional components that characterize modern financial systems. These are

- Stable government finances and public debt management

- A stable monetary unit and a national currency

- A central bank to aid governmental finances and promote overall financial stability

- A banking system to provide the economy with credit and means of making payments

- Securities markets to help governments and businesses to raise capital by issuing bonds and stocks, and to make these securities more attractive to investors and liquid by trading them regularly

- Corporations to raise capital by issuing stocks and bonds to investors and using the proceeds to build large-scale enterprises that can achieve economies of mass production and distribution of goods and services.

It is not far from the truth to say that when Hamilton took office in 1789, the US had none of these key financial components. And that before he stepped down from office in 1795, it had all of them.

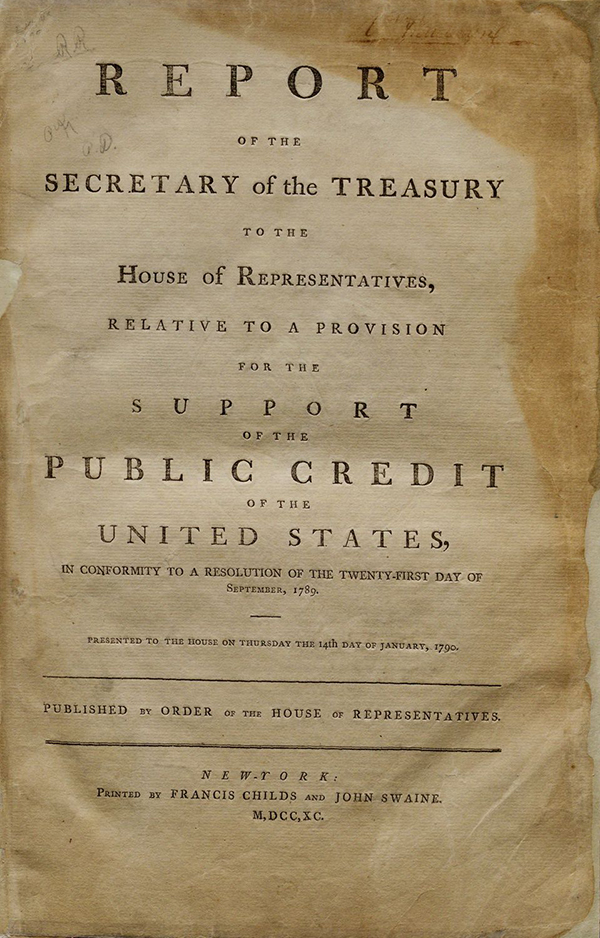

How did he do it? As treasury secretary, Hamilton had the authority to achieve the first three. In his Report on Public Credit of January 1790, he proposed measures to stabilize federal finances, and to restructure and manage the national debt. After much debate and political bargaining, Congress adopted Hamilton’s plan in the summer of 1790. This marked the birth of the US Treasury bond market, which is now the largest in the world for any single issuer of debt.

How did he do it? As treasury secretary, Hamilton had the authority to achieve the first three. In his Report on Public Credit of January 1790, he proposed measures to stabilize federal finances, and to restructure and manage the national debt. After much debate and political bargaining, Congress adopted Hamilton’s plan in the summer of 1790. This marked the birth of the US Treasury bond market, which is now the largest in the world for any single issuer of debt.

In his Mint Report of January 1791, Hamilton proposed a new US dollar as the nation’s monetary base and unit of account. To give it stability, he defined the dollar as specified weights of gold and silver. Congress adopted the plan a year later and established a US mint to make various coins. The US dollar departed from Hamilton’s metallic bases in the twentieth century, but it remains the world’s preeminent national currency.

Hamilton’s Bank Report of December 1790 called for establishing a Bank of the United States as a national bank and in some ways a modern central bank. Congress adopted the bank plan in 1791. When the bank’s twenty-year charter expired in 1811, Congress did not renew it. Soon realizing that was a mistake, Congress established a second bank in 1816. It too was not renewed. But our modern Federal Reserve System established in 1914 is similar enough to the two earlier central banks that it might be considered the third Bank of the United States.

How were the other three key components achieved? Hamilton had the US government own twenty percent of the Bank, and he said the government would profit from that investment. It did, and the lesson was learned by state governments, which began to charter more and more banks, often investing in them. By the early twentieth century, the US had by far the world’s largest banking system.

State governments also chartered more and more non-bank corporations. By the early twentieth century, the US had a majority of all the world’s business corporations.

All the new US government bonds and bank stock created by Hamilton’s program led to the emergence of modern securities markets, even stock exchanges, in several cities. A well-known example is the New York Stock Exchange, long the world’s largest securities market, which traces its origins to 1792, in the midst of Hamilton’s financial revolution.

Finally, Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures of December 1791, his most visionary state paper, made the case that manufacturing would be the economic wave of the future, and that government support could hurry it along. He proposed subsidies and mildly protective import tariffs to encourage the growth of US manufacturing and a more diversified economy. Congress shunned the subsidies, but enacted most of the tariff proposals in 1792. Hamilton also proposed that the federal government establish its own armories and arsenals to manufacture and store weapons. Congress shortly adopted the proposal, and federal armories subsequently became hotbeds of the new manufacturing technologies of mass production and interchangeable parts. Eventually, governments, often state governments, enacted other proposals of the report, such as government aid and sponsorship of transportation and communication improvements.

Most likely no one in 1790 would have forecast that within a century the US would become the world’s largest economy and leading manufacturing nation. No one, perhaps, except Alexander Hamilton.

Richard E. Sylla is professor of economics, emeritus, at the Leonard N. Stern School of Business, New York University. He is the author of Alexander Hamilton: The Illustrated Biography (Union Square & Co., 2016) and the co-author, with David J. Cowen, of Alexander Hamilton on Finance, Credit, and Debt (Columbia University Press, 2018).

[1] See Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987).