The Lives of Andrew Carnegie

by Gordon Hutner

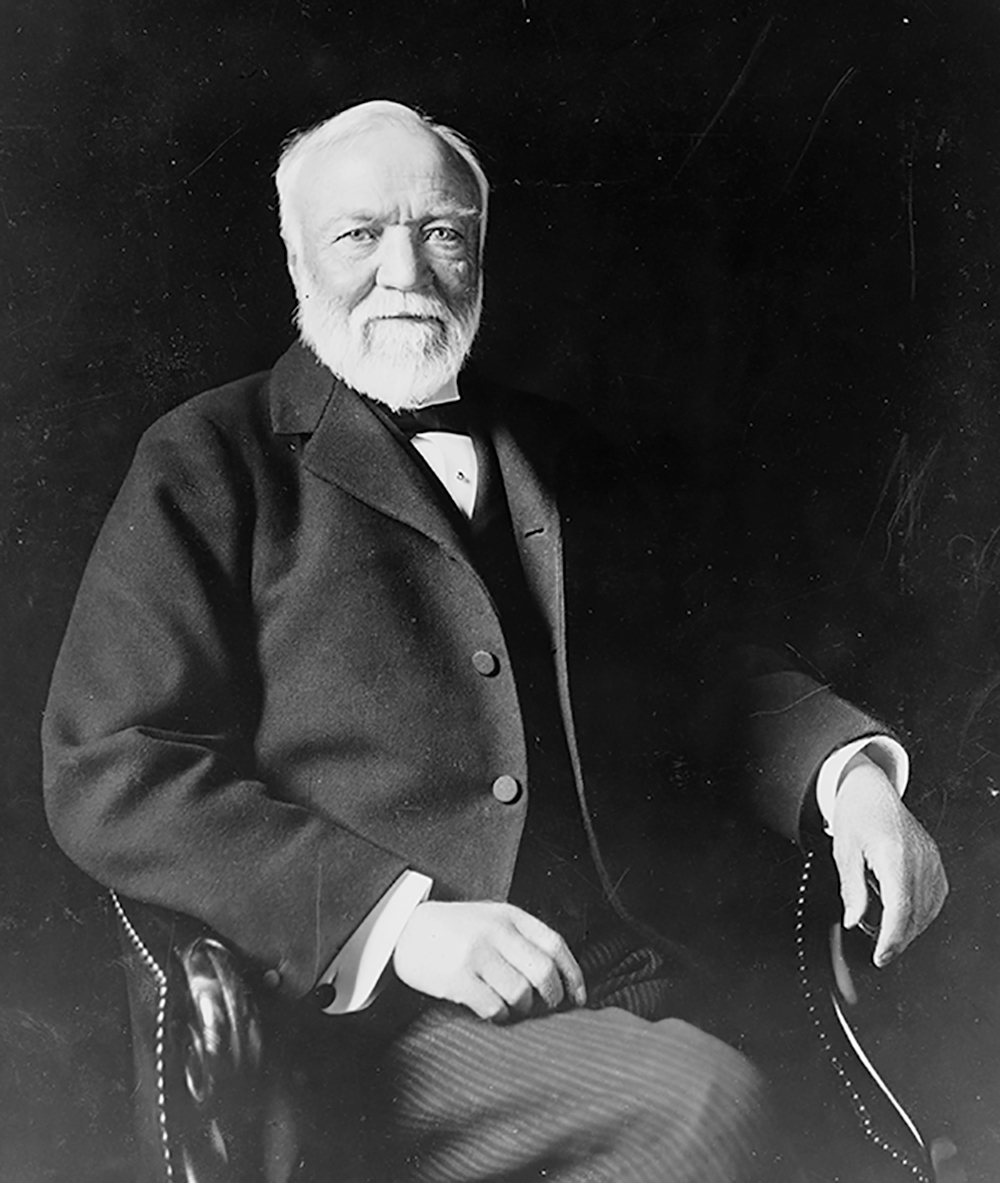

One of the most prominent businessmen in American history, Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as a public figure of complex and enduring interest. He began poor and made a great deal of money, leaving his imprint on several industries, especially railroads, bridge-building, and steel manufacturing. He also emerged as a titan of American finance. At the same time, more than any other business titan of his generation, he undertook unprecedented philanthropic measures, furthering such ends as literacy and education as well as international peace, devoting untold millions to dozens of organizations dedicated to the betterment of peoples throughout the world. Carnegie’s name is still remembered in the corporations, libraries, and the university he founded. His story has been told many times and, during his lifetime, his name was even a byword for the tale of an impoverished boy who, like the hero of a Horatio Alger novel, was “born to rise.”

One of the most prominent businessmen in American history, Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as a public figure of complex and enduring interest. He began poor and made a great deal of money, leaving his imprint on several industries, especially railroads, bridge-building, and steel manufacturing. He also emerged as a titan of American finance. At the same time, more than any other business titan of his generation, he undertook unprecedented philanthropic measures, furthering such ends as literacy and education as well as international peace, devoting untold millions to dozens of organizations dedicated to the betterment of peoples throughout the world. Carnegie’s name is still remembered in the corporations, libraries, and the university he founded. His story has been told many times and, during his lifetime, his name was even a byword for the tale of an impoverished boy who, like the hero of a Horatio Alger novel, was “born to rise.”

By the end of his life, Carnegie was often considered a representative American, one whose biography fulfilled the promise of a nation developing into a world power. Yet his success was also controversial insofar as he was also reputed to be a ruthless industrialist and exploitative monopoly capitalist, a robber baron reviled as much as he was admired. Unlike any other American man of business, Carnegie envisioned a “gospel of wealth,” the good it could do, and the disgrace of failing to return his fortune to the needy. As he put it, a man should endeavor to spend the first third of his life immersed in education; the second third, devoted to the accumulation of wealth; and the final third, dedicated to an energetic philanthropy. Carnegie shared his political and social views in the many books and essays that he wrote, leaving an unprecedented record of his ideals and purposes. Those writings also reflected his long record of associating himself with writers and thinkers, along with politicians and other public figures of the day, for once Carnegie determined to give away his fortune, he developed still another career as a social observer and advocate.

Carnegie began life in Dunfermline, Scotland, a town some forty miles from Edinburgh. At one time financially secure, his grandfather’s and his father’s livelihoods as weavers were endangered as a result of the mechanization of the textile industry. By the time “Andra” was born, the family faced increasingly precarious financial circumstances. While weaving was the trade his father could introduce him to, on his mother’s side, he was supported by a tradition of vigorous political commitment, especially through the activities of his maternal grandfather and an uncle who found his voice as a local orator. The Morrisons espoused a vision of a shared nationalized wealth and greater democratic opportunity than was otherwise available in the United Kingdom, political values associated with Chartism, a populist midcentury working-class movement committed to extending the voting franchise beyond property owners. Still another uncle instructed Andra in the richness of his Scottish literary heritage, including the poetry of Robert Burns and its Romantic folklore, associations he always held dear, especially in the charity he later bestowed in Scotland.

These foundations helped to shape Carnegie’s thinking, but the family’s economic prospects were so grim that his mother, Mary, took charge of its plight and planned their emigration to the US when the boy was twelve. They moved to western Pennsylvania, where she had sisters in Pittsburgh and settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in squalid circumstances. His father initially was employed in a cotton textile factory, where his son, now called Andy, went to work as a bobbin boy, whose demanding, sometimes dangerous job it was to carry racks of empty spools from the winding machines to the loom operators and retrieve the racks of full spools.

With this job came the end of Carnegie’s formal schooling and the beginning of his working life. His teenage years were spent in a variety of positions, and his first break came while he was working as a messenger for a telegraphy office, where he immediately won favor for his promptness and command of delivery addresses. Soon he was given the job of telegrapher, in which capacity he further excelled for his ability to transcribe messages from voice to telegraphy keys, without the time-consuming practice of referring to hard copy. That talent, and his astonishing work ethic, was soon noticed by the regional superintendent of the Pennsylvania railroad, Thomas A. Scott, who hired young Andrew as his private secretary.

It was under Scott’s tutelage that Carnegie achieved the education that he would draw upon for the rest of his life. Scott instructed the young man in his first lessons in finance: how money can be used to make money. Scott lent Andrew the money to buy ten shares in a stock, and, as he records in his autobiography, when Carnegie received his first dividend—the first money anyone in his family had made without physical labor—it was a “Eureka” moment: “Here’s the goose that lays the golden eggs.”[1] Soon Carnegie made other investments, including an oil well and a share in a sleeping-car company. When Scott was made in charge of the rail transport of soldiers at the onset of the Civil War, Andrew joined him in Washington, briefly, before an attack of sunstroke—a sensitivity he suffered throughout his life—led to his return to Pittsburgh where he had already succeeded Scott as the Western Division superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

During the war, Carnegie began his career as a bridge builder, using the connections he had made in Pittsburgh’s iron mills. With an interest in the iron business stemming from the axles he needed to purchase for his railroad car business, Carnegie realized that he could use those resources for the construction of iron bridges throughout the country in support of rail travel and transport. Through some boyhood connections, he was drawn more deeply into the iron business and soon found himself in control of one iron mill, a business that grew exponentially over the years. When he sold Carnegie Steel to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $480 million dollars, it became US Steel.

During the war, Carnegie began his career as a bridge builder, using the connections he had made in Pittsburgh’s iron mills. With an interest in the iron business stemming from the axles he needed to purchase for his railroad car business, Carnegie realized that he could use those resources for the construction of iron bridges throughout the country in support of rail travel and transport. Through some boyhood connections, he was drawn more deeply into the iron business and soon found himself in control of one iron mill, a business that grew exponentially over the years. When he sold Carnegie Steel to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $480 million dollars, it became US Steel.

After the war, Carnegie found even more investment opportunities, most notably the Pullman railroad car company and the Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph company, later sold off to Western Union. Such lucrative experience established Carnegie as a figure of considerable consequence, and he soon moved to New York to manage his business affairs. In New York, he began to expand his social circle, but he still concentrated ferociously on his business career, especially iron, buying up competitors wherever he could. A favorite adage of his captures his redoubtable single-mindednes about business: “Put all good eggs in one basket,” he counseled, “and then watch that basket.”[2] As part of that focus, Carnegie aimed to take advantage of every technical advance in the production of iron and steel that he could, particularly the Bessemer process of purifying the molten iron out of which steel could be much more inexpensively produced.

Carnegie believed that his company should strive for what he called “verticality,” by which he meant that the company should be organized by drawing on its own natural resources, its own production, its own transportation, and its own distribution, rather than by collaborating with other businesses. To achieve this, Carnegie determined that he must take care to find the most efficient means to conduct any process in all the subsidiaries, to weed out any waste, and to find profit at every turn. And while he began his career with a respect for his employees, as he prospered he took a dimmer view of their right to organize in unions. Watching the basket thus became the importance of organizing a monopoly, which he pursued resolutely. He owed his success to his penchant to “push inordinately” to seek a business advantage and then exploit it.

Carnegie wanted always to enjoy a certain fellowship with his workers, especially those from Scotland. However, his employees were not altogether enamored of the Carnegie method. Their discontent famously came to a head in the Homestead Strike of 1892, when Carnegie and his partner Henry Clay Frick were determined to break the steel workers’ union at one of their factories, hiring a private army of Pinkertons who engaged the strikers in a daylong gun battle, leading the governor to call in the state militia. Carnegie hated the bad publicity that his efforts at suppression caused and tried to blame Frick for the mismanagement as he was en route to Scotland for his annual visit, but the historical record is clear that Frick did not act on his own authority alone.

Countering the image of Carnegie as some fierce magnate contemptuous of the people he plowed over in his rise to the pinnacle of American wealth and power is the astonishing record of charity that Carnegie began early in his career and that was sustained long after his death. Upon his retirement, he generously endowed a pension fund for former Homestead steelworkers. He also created a fund to reward heroic actions. His philanthropies included 2,811 free public libraries, parks, public swimming baths, and a plan to provide thousands of churches with organs. While Carnegie was no great admirer of academic life, his Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching included pensions for college teachers as well. He did, however, underwrite institutes for scientific and medical research, including the one that became Carnegie Tech and later Carnegie-Mellon University. He also endowed the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. In 1891, he also established a world-class concert venue, Carnegie Hall, in New York City. And the mansion Carnegie built in his adopted city now stands as the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. These comprise merely a partial list of his philanthropic accomplishments, perhaps the most aspirational of which were his efforts to abolish war and to promote peace, primarily through the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which today continues his efforts to create and adapt strategies for solving international conflict. He also funded the construction of the Peace Palace at The Hague, intended to house the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

In 1891, he also established a world-class concert venue, Carnegie Hall, in New York City. And the mansion Carnegie built in his adopted city now stands as the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. These comprise merely a partial list of his philanthropic accomplishments, perhaps the most aspirational of which were his efforts to abolish war and to promote peace, primarily through the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which today continues his efforts to create and adapt strategies for solving international conflict. He also funded the construction of the Peace Palace at The Hague, intended to house the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Carnegie wrote three travel books and assembled his essays in various collections. Perhaps the book he was best known for in his lifetime was his Gospel of Wealth, wherein he outlined his vision of the obligations of the wealthy toward society. The book he was perhaps proudest of was Triumphant Democracy (1886), wherein he makes the case for the superiority of American republicanism over the monarchical power still regnant in the UK that he believed stifled individual striving and discouraged business success. And perhaps the book by which he will most be remembered is his Autobiography, published the year after he died at the age of eighty-four. It marked the appearance of the first truly notable memoir of an American capitalist, vividly telling the story of the penniless bobbin boy’s rise from a $1.20-per-week salary to the selling of Carnegie Steel for nearly a half a billion dollars (nearly $16 billion when adjusted for inflation). Unlike Benjamin Franklin, whose autobiography taught that the way to wealth is to make yourself useful in your time and your milieu, Carnegie taught that getting rich requires both a tough-minded determination and a thorough, equally unflagging dedication to do good.

Gordon Hutner is professor of English, director of the Trowbridge Initiative in American Cultures, and the American Studies Program coordinator at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of various writings on American literary history, including the introduction to The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie and His Essay “The Gospel of Wealth” (Signet Classics, 2006).

[1]Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, ed. John C. Van Dyke (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 80.

[2]Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, ed. John C. Van Dyke, 176.