Venture Smith: African American Founding Father and Entrepreneur

by Chandler B. Saint

Today, Venture Smith (born Broteer Furro in West Africa in 1729) is often referred to as the archetypal self-made man, a shining example of the American Dream. Unlike Horatio Alger and others, however, he did not have a benefactor, family support, or capital to build on. Venture’s capital was his own knowledge and understanding of how trade worked, which he acquired by observing and absorbing the business practices of the people he served—the very people he would join as patriots and then business partners during and after the Revolutionary War.

Today, Venture Smith (born Broteer Furro in West Africa in 1729) is often referred to as the archetypal self-made man, a shining example of the American Dream. Unlike Horatio Alger and others, however, he did not have a benefactor, family support, or capital to build on. Venture’s capital was his own knowledge and understanding of how trade worked, which he acquired by observing and absorbing the business practices of the people he served—the very people he would join as patriots and then business partners during and after the Revolutionary War.

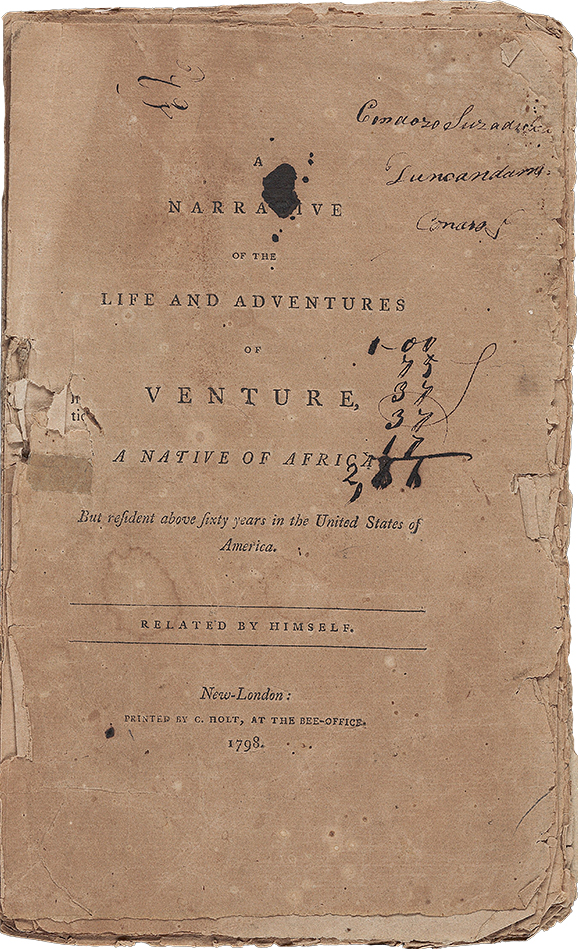

Born the son of a king and destined to become one of the principal chiefs of his country, Broteer was extensively tutored as a youth in farming, commerce, and statecraft. He learned from his father how to run a country and negotiate and trade with others. By the time he was captured in late 1738, his formal education was complete and he had gone through a ceremonial passage to adulthood. He survived the Middle Passage in 1739, and on the voyage was taught some English and the basics of being a sailor by his new owner, Robinson Mumford, steward of the Rhode Island ship Charming Susanna. Venture went on to learn and master English from his educated and articulate owners, the Mumfords, Daniel Edwards Esq., and Oliver Smith. He could speak eloquently, became an accomplished writer, and in 1798 wrote his autobiography, an American classic.

Venture Smith was enslaved for twenty-six years by members of prominent New England trading families. His last owner, Oliver Smith, of Stonington, Connecticut, consented in 1760 to Venture buying his freedom. Once given the chance to work for himself, he knew how to manage and excel at business and trade. Venture worked for five years to buy his freedom in 1765, and then nine years more to buy his wife Meg, his children Hannah, Solomon, and Cuff, and three other Africans. By 1774, living on Ram Island in Southampton, Long Island, he had become successful.

In 1774 as events unfolded, such as the Intolerable Acts, the Suffolk Resolves, and the continuing tea parties in numerous colonies, it became clear that the king and Parliament were taking away the rights of the colonists for self-government and the ability to trade.[1] Colonials like Venture, who were free subjects of the British Crown, were focused on deciding their future—where to live and which government to support.

For Venture, the future was not going back to Africa, to England, to Nova Scotia, or staying on Long Island awaiting an invasion by the British army. When the Continental Congress passed the Articles of Association on October 20, 1774, Venture knew the die was cast, and he chose to move to Connecticut and build a future for himself and his family in the new country.

The most astute decision of Venture’s life was like that of the other founding fathers—to risk everything, join the patriot cause, and start a new life on the mainland. Making an early move to the Haddams in Connecticut, which would become a center for trade during the Revolution, would gain him business opportunities with the leaders of Connecticut. Venture moved to East Haddam in mid-December 1774, almost twenty months before his neighbors and other leading families of eastern Long Island would join the exodus. He was immediately welcomed and given the opportunity to buy land, partner with establishment figures, and begin building his future. The majority, who waited until after Long Island fell to the British on August 29, 1776, had a very different experience. In September 1776, some 3,500 people left from the docks at Sag Harbour for Connecticut. To leave Long Island for the mainland they had to secure permits which formally designated them as “Refugees.” When they arrived, although welcomed, they had to prove their loyalty and found housing scarce and jobs few. They did not even have the right to vote.[2]

Venture’s experience was very different. On Friday March 3, 1775, he purchased his first ten acres on Haddam Neck—the vindication of his decision to risk all by joining the patriots in Connecticut. One can only imagine Venture’s pride and elation when sharing with his family the deed, containing the words “Venture a free negro Resident in Haddam.” Venture was now a freeholder and therefore a citizen of the Colony of Connecticut. In May 1775 when the Continental Congress convened, Venture would have been become one of the first African-born citizens of the new country.[3]

The first thing Venture did on his land was to start cutting trees and stacking firewood to age, and taking logs to the local sawmill to cut the boards he would sell or use to build his house. By 1777 the first wood was ready for market and he used the money earned to buy more land and to build his house. By 1778 he had more than 130 acres of land, which was a symbol of freedom in the early republic.

As he cleared the land, he began to grow wheat, vegetables, and fruit, and raise sheep, cattle and pigs. He would have sold fruits and vegetables at the local town markets, wood to Rhode Island, and traded produce on Long Island for fish, clams, eels, and oysters that he would bring back and sell up and down the Connecticut River. Venture maximized his profit by selling his products and produce directly to consumers. By transporting his firewood to Newport and Providence himself, he cut out the middleman.

Venture and other Connecticut and Rhode Island traders such Nathaniel Shaw, the Mumfords, and the Denisons succeeded because they diversified and quickly adapted to market changes and circumstances. Quintessential Yankees, they were flexible and opportunistic, not dependent on the annual success of a single crop like the farmers of tobacco, grain, or cotton. Their smaller sloops and brigs were designed for multipurpose use, and were retrofitted for each voyage—carrying cargo to the West Indies, whaling in the Atlantic, sailing to Africa for slave voyages, or taking oil and rum to England. In shipping they also spread their risks by taking shares in a boat. On a whaling voyage, Oliver Smith would invest in a third of three different ships rather than run the risk of owning one ship and losing it in a storm.

![Headstone of Venture Smith [Broteer Furro] in the First Congregational Church Cemetery in East Haddam, Connecticut (Personal collection of Chandler B. Saint)](/sites/default/files/2025-12/VentureSmithGravestone_Saint.jpg) When going to the West Indies, these traders usually took at least six or seven different products—from lumber to foodstuffs and even trotting horses and ice for the planters. They were flexible in selling—taking cash, goods (sugar or molasses, oranges, pineapples, and other tropical delicacies), or third-party notes of credit from merchant houses in London. The sugar was brought back and turned into rum and sold for cash, taken to Africa to trade for slaves, or transported to London and sold for cash or traded for manufactured goods. The goal was to make a five-percent commission on every trade.

When going to the West Indies, these traders usually took at least six or seven different products—from lumber to foodstuffs and even trotting horses and ice for the planters. They were flexible in selling—taking cash, goods (sugar or molasses, oranges, pineapples, and other tropical delicacies), or third-party notes of credit from merchant houses in London. The sugar was brought back and turned into rum and sold for cash, taken to Africa to trade for slaves, or transported to London and sold for cash or traded for manufactured goods. The goal was to make a five-percent commission on every trade.

Venture does not tell us what he did in the Revolution—many veterans never talk about their war—but we do know that four Revolutionary War officers or privateers he knew and worked with for years certified his autobiography in 1798. When he died in 1805 his comrades came to honor him. Four men bore his coffin three and a half miles through East Haddam, among them a Revolutionary War infantry officer, the son of another, and a proxy for a general. Although racism based on skin color was becoming part of American culture, Venture was buried by his former comrades, local friends, and business partners, as a founding father, a peer of the community, and citizen of Connecticut and the United States of America.

Chandler B. Saint is co-director of the Documenting Venture Smith Project, a fellow of the Wilberforce Institute at the University of Hull, and president of the Beecher House Center for Equal Rights. He is the author of Venture Smith: “My freedom is a privilege which nothing else can equal” (Documenting Venture Smith Project, 2018); editor of The Richardson Series of African Narratives in Translation; creator of the traveling exhibition Venture Smith: American; and editor of numerous editions of Venture Smith’s 1798 autobiography, including one in Fante (the first time a work by a survivor of the Middle Passage has been translated into an African language).

[1] For further reading, see Mary Beth Norton, 1774: The Long Year of Revolution (Alfred A. Knopf , 2020).

[2] For additional context, see Frederic Gregory Mather, The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut (J. B. Lyon Company, 1913).

[3] The framers of the Constitution, as per Article II, Section 1, paragraph 5, recognized the United States as having been founded in 1775, first called the United Colonies of North-America, then renamed the United States of America in 1776.