The Fight for LGBT Rights after World War II

by Timothy Stewart-Winter

The oppression of LGBT Americans did not begin in the post–World War II decades, but they faced increasingly systematic exclusion from public life, in part resulting from the Cold War political climate of fear and distrust of people who deviated from social norms. In response, LGBT Americans challenged their marginalization. The gay and lesbian movement gained steam after the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City. By the 1980s, gay and lesbian people gained political influence in a few American cities, even as the HIV/AIDS crisis posed a new threat.

The oppression of LGBT Americans did not begin in the post–World War II decades, but they faced increasingly systematic exclusion from public life, in part resulting from the Cold War political climate of fear and distrust of people who deviated from social norms. In response, LGBT Americans challenged their marginalization. The gay and lesbian movement gained steam after the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City. By the 1980s, gay and lesbian people gained political influence in a few American cities, even as the HIV/AIDS crisis posed a new threat.

During World War II, military service and jobs in war industries pulled millions of Americans out of their communities of origin, and many gay and lesbian people encountered others like themselves for the first time. In the 1950s, even as Alfred Kinsey’s studies raised awareness about gay life, urban police increasingly spied on, arrested, and jailed LGBT people and closed their establishments. In 1952, in the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, American psychiatrists newly labeled homosexuality as a mental illness. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s investigation into communism helped fuel a similar, even larger effort to root out gay and lesbian federal employees. Corporations followed suit in investigating and firing gay employees.

Demonized in the media, most gay and lesbian people concealed their homosexuality from their friends and relatives. Yet the intensity of anti-LGBT oppression also led some gay people to challenge the social and political structures that oppressed them. A few gay people quietly launched gay rights organizations in cities. One leader in this effort was Frank Kameny, a government astronomer fired for being gay in 1957, who challenged his dismissal.

In the mid-1960s, Kameny and other “homophile” activists held the first gay and lesbian pickets against antigay policies, modeled on Black civil rights protests, while other LGBT people fought back against police harassment. In 1969, a routine police raid on a New York City gay bar, the Stonewall Inn, led to several nights of rioting, with homeless street youth and people we would now call transgender the first to fight back. Building on movements against the Vietnam War and for Black Power and women’s liberation, a new generation of activists for “gay liberation” disclosed their homosexuality, which they called “coming out of the closet.” They launched parades through city streets to commemorate “Gay Pride” on the anniversary of Stonewall, challenging the public invisibility of LGBT people.

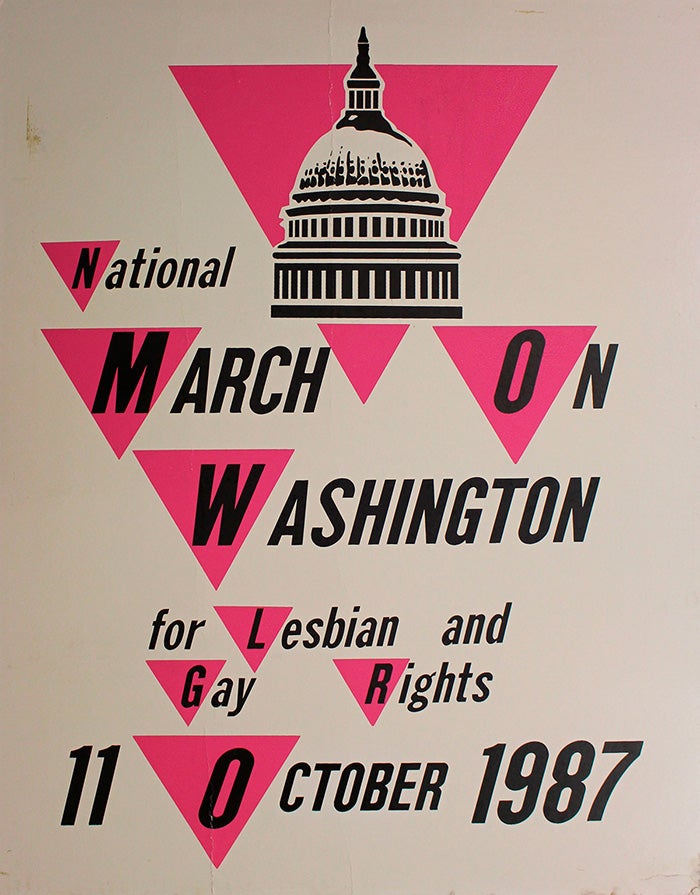

By the 1970s, a few openly gay and lesbian people ran for political office, including Harvey Milk, elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. Yet LGBT visibility also inspired backlash. A new movement for traditional family values exploited prejudices and especially demonized gay and lesbian schoolteachers. In the 1980s, the onset of the HIV/ AIDS crisis led to the deaths of many gay and bisexual men, intravenous drug users, and others. The epidemic led to a resurgence of radical gay activism, including the militant organization ACT UP, which challenged government neglect of the crisis.

In the 1990s, the LGBT movement was transformed by a debate over military service by gay and lesbian people, as well as by medical advances in the treatment of HIV, increased visibility in popular culture, and demands by transgender people for inclusion and representation. In a landmark 2003 ruling, Lawrence v. Texas, the US Supreme Court struck down state laws criminalizing gay sex; in the decade after Lawrence, state court decisions legalizing same-sex marriage sparked a major backlash and national debate. During the presidency of Barack Obama, Congress repealed the ban on gay military service, and public opinion shifted dramatically in favor of marriage equality, which was legalized nationwide in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

Timothy Stewart-Winter, associate professor of American studies, women’s and gender studies, and history at Rutgers University-Newark, is the author of Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics.