"To give all a chance": Lincoln, Abolition, and Economic Freedom

by Lewis E. Lehrman

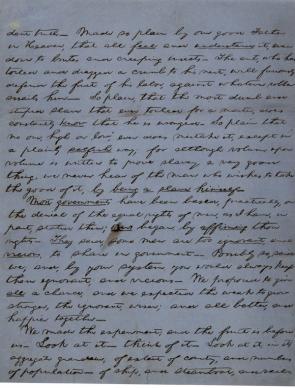

To read carefully the Lincoln economic parable of the ant (reprinted here) suggests a lost truth about our sixteenth president: during most of Abraham Lincoln’s political career he focused not on anti-slavery but on economic policy. Yet anti-slavery and economic policy, in his worldview, were tightly linked. As Lincoln explained, slavery was grounded in coercion. It was, and is, an involuntary economic exchange of labor. In commercial terms, slavery is theft: “The ant, who has toiled and dragged a crumb to his nest, will furiously defend the fruit of his labor, against whatever robber assails him . .&nsp;. the most dumb and stupid slave, that ever toiled for a master, does constantly know that he is wronged.”[1] Slavery differs from free labor as a beast does from a man. Thus Lincoln assailed slavery not only on moral grounds but also on economic principle. This principle, he asserted, is a truth “made so plain by our good Father in Heaven, that all feel and understand it, even down to brutes and creeping insects.”[2] We must not be misled by Lincoln’s simple metaphors, for one of the profound strengths of Lincoln’s political philosophy was his self-taught and masterful grasp of economic theory, more sophisticated than that of any President before or since. This is, I think, an inescapable conclusion from any careful study of Lincoln’s collected writings, speeches and state papers.

To read carefully the Lincoln economic parable of the ant (reprinted here) suggests a lost truth about our sixteenth president: during most of Abraham Lincoln’s political career he focused not on anti-slavery but on economic policy. Yet anti-slavery and economic policy, in his worldview, were tightly linked. As Lincoln explained, slavery was grounded in coercion. It was, and is, an involuntary economic exchange of labor. In commercial terms, slavery is theft: “The ant, who has toiled and dragged a crumb to his nest, will furiously defend the fruit of his labor, against whatever robber assails him . .&nsp;. the most dumb and stupid slave, that ever toiled for a master, does constantly know that he is wronged.”[1] Slavery differs from free labor as a beast does from a man. Thus Lincoln assailed slavery not only on moral grounds but also on economic principle. This principle, he asserted, is a truth “made so plain by our good Father in Heaven, that all feel and understand it, even down to brutes and creeping insects.”[2] We must not be misled by Lincoln’s simple metaphors, for one of the profound strengths of Lincoln’s political philosophy was his self-taught and masterful grasp of economic theory, more sophisticated than that of any President before or since. This is, I think, an inescapable conclusion from any careful study of Lincoln’s collected writings, speeches and state papers.

Although Lincoln’s nationalist economics were unmistakably Hamiltonian in policy, we still hear in his speeches the echoes of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. On his way to Washington in early 1861, he declared in Philadelphia, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”[3] “Most governments have been based, practically, on the denial of the equal rights of men,” he had written earlier. “Ours began, by affirming those rights.”[4] But only free labor can exercise equal rights. Lincoln’s re-affirmation of this principle at Gettysburg in 1863 evoked “a new birth of freedom.” At Gettysburg he insisted that America—despite the flaw of slavery, accepted in order to establish the Constitution—had been “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”[5] One year later, combining the ideas of the great adversaries of the early republic—Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson—President Lincoln explained to Ohio soldiers visiting the White House that the Civil War itself was a struggle to create “an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence; that you may all have equal privileges in the race of life.”[6] Then came the Emancipation and Civil Rights Amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

From time immemorial, Americans have struggled to be different from other nations. Bound together neither by race and blood, nor by ancestral territory, Americans inherit but a single patrimony: equality under the law and equality of opportunity. That Abraham Lincoln’s equality was equality of opportunity cannot be denied. “I think the authors of that notable instrument [the Declaration of Independence] intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal—equal in ‘certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.’”[7] This is what the emancipator said; and this is what he meant: “We proposed to give all a chance; and we expected the weak to grow stronger, the ignorant, wiser; and all better, and happier together.”[8] And so, to be stronger and wiser, Americans have ever been ambitious for their liberal democracy. Lincoln, too, was ambitious. Indeed, he was history’s most ambitious nation builder. Lincoln’s law partner, William Herndon, described Lincoln’s ambition as “a little engine that knew no rest.”[9]

Lincoln was ambitious to use government to good effect. Government, he believed, should enable men and women to develop their freedom, their future, and their country. In his earliest political years, as a state legislator, Lincoln urged that government should be pro-labor and pro-business. During the decades before his presidency, he advocated government support in creating canals, railroads, banks, turnpikes, a national bank—all needed to integrate a national market—to the end of increasing opportunity, social mobility, and productivity. Like the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, Lincoln sponsored an “American System.” As an economic nationalist, he advocated a tariff to give the competitive advantage to American workers and American firms, and to enhance American independence. As a sophisticated student of banking and monetary policy, Lincoln argued throughout his political career for a sound national currency.

His economic philosophy rejected the idea of necessary conflict between labor and capital, believing them to be cooperative in nature. Cooperation could, in a society of free labor, lead to economic growth and increasing opportunity for all. In fact, Lincoln argued that capital was, itself, the result of the savings of free labor. Wrought by the mind and muscle of men, the products of labor yield savings, which are then deployed as capital. Thus, it follows that people are the most important resource, not wealth. This proposition was so important that President Lincoln argued in his first annual message to Congress in 1861 that “labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed.”[10] (Even “the ant will furiously defend the fruit of his labor.”[11])

Nineteenth-century echoes of Lincoln’s speeches roll down like thunder in the twentieth-century voice of Martin Luther King, Jr. For it was Lincoln who defined the essence of the American dream: “There is not, of necessity any such thing as the free hired laborer being fixed to that condition for life. . . . The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This is the just, and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way to all—gives hope to all, and . . . energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all.”[12] More than one hundred years later, King called for the economic rights that would take African Americans one step closer to freedom: the Negro’s “unpaid labor made cotton king and established America as a significant nation in international commerce. Even after his release from chattel slavery, the nation grew over him, submerging him. . . . And so we still have a long, long way to go before we reach the promised land of freedom.”[13]

From his deep experience, Lincoln had developed tenacious convictions. Born poor, he was probably the greatest of truly self-made men, believing, as he said, that “work, work, work, is the main thing.”[14] His economic policy was designed not only “to clear the path for all,” but to spell out incentives to encourage entrepreneurs to create new jobs, new products, new wealth. He believed in what historian Gabor Boritt has called “the right to rise.”[15] Lincoln’s America was, in principle, a colorblind America. “I want every man to have the chance,” Lincoln announced in New Haven in March 1860, “and I believe a black man is entitled to it . . . when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system.”[16]

In Lincoln’s American system, government fosters growth. Equal opportunity leads to social mobility. Intelligence and free labor lead to savings and entrepreneurship. Such a colorblind economic system was the counterpart of the Declaration’s colorblind equality principle. The great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass saw this clearly, pronouncing the fitting tribute when he said of President Lincoln that he was “the first great man that I talked with in the United States freely, who in no single instance reminded me . . . of the difference of color.” He attributed Lincoln’s attitude to the fact that he and Lincoln were self-made men—“we both starting at the lowest rung of the ladder.”[17]

President Lincoln’s political and wartime legacy has transformed world history. As a last resort, he accepted war to preserve the Union, and with war, to free the slaves: “It is an issue which can only be tried by war, and decided by victory.”[18] His grim determination to fight on to victory was not imprudent, he argued: “The national resources . . . are unexhausted, and, as we believe, inexhaustible.”[19] Without Lincoln’s leadership and resolve, separate slave and free states might today compete on the same continent. There would be no integrated, peerless American economy based on free labor. But without continental American industrial power, which Lincoln self-consciously advocated, the industrial means would not have been available to contain Imperial Germany as it reached for European hegemony in 1914. Neither would there have been a national power strong enough to destroy its successor, Hitler’s Nazi Reich, nor to crush the aggressions of Imperial Japan. And, in the end, there would have been no unified, continental American power to oppose and overcome the Communist empire of the second half of the twentieth century. Empires based on the invidious distinctions of race and class—the defining characteristics of the malignant world powers of our era—were preempted by the force and leadership of a single world power, the United States of America. In Lincoln’s words, “We made the experiment; and the fruit is before us. Look at it—think of it. Look at it, in its aggregate grandeur, of extent of country, and numbers of population—of ship, and steamboat, and rail-[road].”[20]

Hovering over the whole history of Lincoln’s pilgrimage, there still lingers the enigma of a very private man—the impenetrable shadow of his profile. We scrutinize Lincoln’s character; but we see him through a glass darkly. So we mine his papers, sap the memoirs left by those who knew him, plumb his personal relationships. But he escapes us.

Surely we know about his humble parents, his lack of formal education, his discreet but towering ambition. But we wonder that—unlike the Adamses, the Roosevelts, the Kennedys, the Bushes—no descendants carried on his legacy of national leadership. Like a luminous comet, he had for a twinkling thrust himself before our eyes, the eyes of the world, there to dissolve into the vasty deep whence he came.

[1] Abraham Lincoln, Fragment on Slavery, [1857–1858?], reprinted here from the Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC03251 (cited hereafter as GLC03251); also printed in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 2:222. This document is an undated page of a manuscript by Abraham Lincoln, possibly written as part of a speech given in 1857–1858.

[2] GLC03251 and Collected Works, 2:222.

[3] Abraham Lincoln, Speech in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pa., February 22, 1861, Collected Works, 4:240–241.

[4] GLC03251 and Collected Works, 2:222.

[5] Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863, Collected Works, 7:22.

[6] Abraham Lincoln, Speech to One Hundred Sixty-sixth Ohio Regiment, August 22, 1864, Collected Works, 7:512.

[7] Abraham Lincoln, Speech at Springfield, Ill., June 26, 1857, Collected Works, 2:405–406.

[8] GLC03251 and Collected Works, 2:222.

[9] William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Lincoln: The History and Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Albert & Charles Boni, 1930), 304.

[10] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1861, Collected Works, 5:52

[11] GLC03251 and Collected Works, 2:222.

[12] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1861, Collected Works, 5:52

[13] Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard, eds. A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books Inc., 2001), 182.

[14] Abraham Lincoln, Letter to John M. Brockman, September 25, 1860, Collected Works, 4:121.

[15] See Gabor S. Boritt, Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream (Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1978).

[16] Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Conn., March 6, 1860, Collected Works, 4:24–25.

[17] Allen Thorndike Rice, ed., Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time (New York: North American Publishing Co., 1886), 193.

[18] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1864, Collected Works, 8:151.

[19] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1864, Collected Works, 8:151.

[20] GLC03251 and Collected Works, 2:222.

Lewis E. Lehrman is co-chairman of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and co-founder of the Lincoln Prize. His book, Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point, was published in 2008.