Teddy Roosevelt campaigns for a third term, 1912

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Theodore Roosevelt

In February 1912, former president Theodore Roosevelt stunned the country by challenging President William Howard Taft for the Republican nomination. The move was not only a rejection of his friend Taft, it also violated an unwritten rule of American politics. Roosevelt had already had two terms in office, and no president had ever had a third. Roosevelt insisted that he was running out of duty, not personal ambition. As president, he had charted a politically progressive course, but under Taft, his chosen successor, the country had been becoming more conservative.

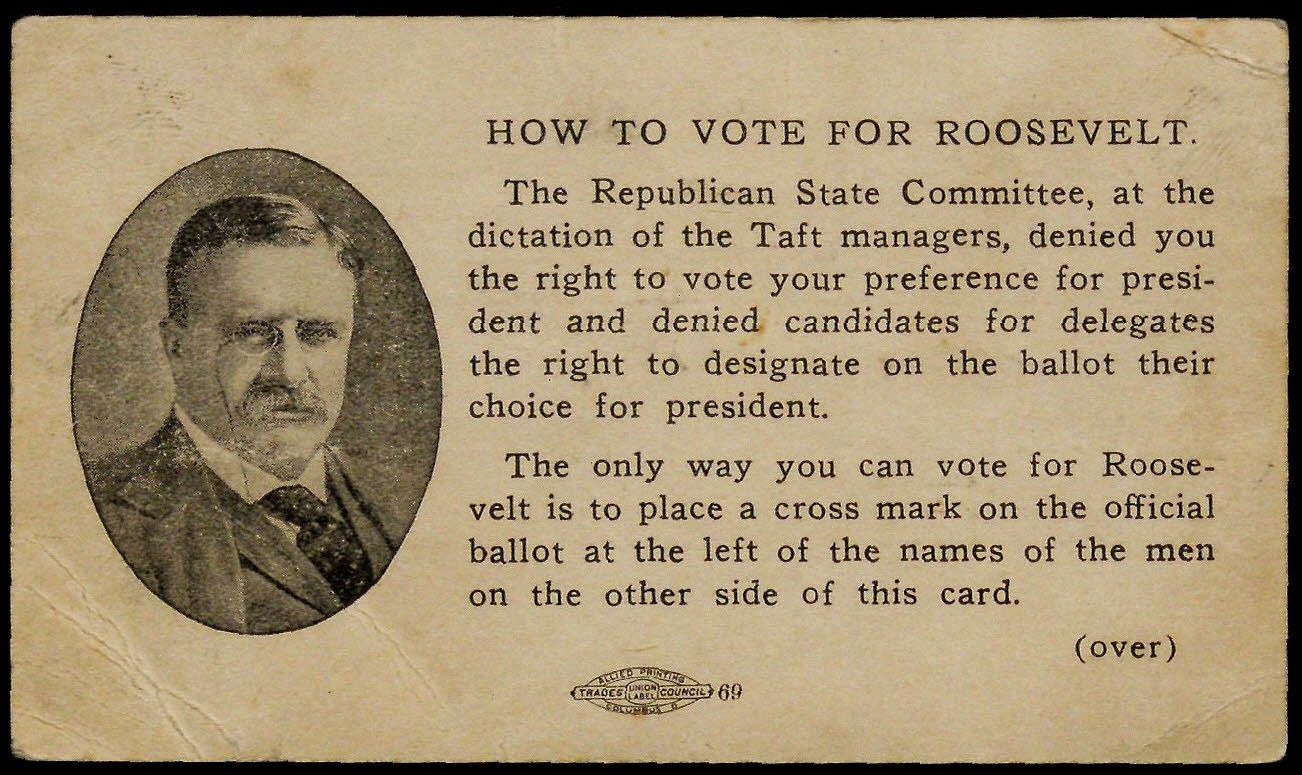

In 1912 primary elections played a big role in presidential politics for the first time, but only twelve out of forty-eight states held primaries. While Roosevelt won those primaries, it became obvious that the party bosses in the non-primary states would give most of the delegates to Taft. In a last-ditch effort to secure the Republican Party nomination, Roosevelt distributed cards such as this one with instructions on how to vote for him at the convention.

When it became clear that Roosevelt would be about seventy votes shy of winning the nomination, he announced he was leaving the Republican Party and forming a new party. Officially known as the National Progressive Party, it became known as the Bull Moose Party when in June 1912 he described himself as “fit as a bull moose.”

Roosevelt campaigned at railroad whistle-stops along the East Coast, across the South, and deep into the Midwest. On the evening of October 14 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, John Schrank shot Teddy Roosevelt in the chest to prevent him from becoming a third-term president. The steel eyeglass case and speech in Roosevelt’s breast pocket slowed the bullet, which lodged in his rib. Doctors decided it was safer to leave it than risk surgery.

The attempted murder sidelined Roosevelt for the rest of his campaign. In a letter dated November 2, just three days before the election, Roosevelt apologized for not being able to speak in Brooklyn. He explained,

I have received many scores of urgent requests to speak in the various cities where it had been announced that I was to speak during the closing fortnight of the campaign-messages from Philadelphia, from Buffalo, from Rochester, from Syracuse and Albany, from Hartford and New Haven, and from many other cities. It was with the most genuine regret that I was obliged to answer that it was a physical impossibility for me to do as I would so like to have done and speak in these cities. Through no fault of mine I was obliged to abandon the engagements I had made and to ask my friends and fellow-citizens to accept a written message from me in lieu of the words I had hoped to speak face to face with them.

With Roosevelt and Taft dividing the Republican vote, Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson won the election. Taft later became Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court. Read more about the election of 1912 here.

The Bull Moose Party collapsed in the midterm elections of 1914 and died in 1916, but the ideals that the Progressives articulated in 1912 lived on in American politics for decades. Their influence can be seen in Woodrow Wilson’s New Freedom, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Many of the Progressives’ ideas had been proposed by candidates in previous elections, but Roosevelt incorporated them into a broad vision of the role that the national government could play in advancing equality. He engaged Americans in one of the most serious conversations they had ever had about who they were as a nation, and what they might become.