African Americans in WWII

Posted by Anna Khomina on Tuesday, 06/20/2017

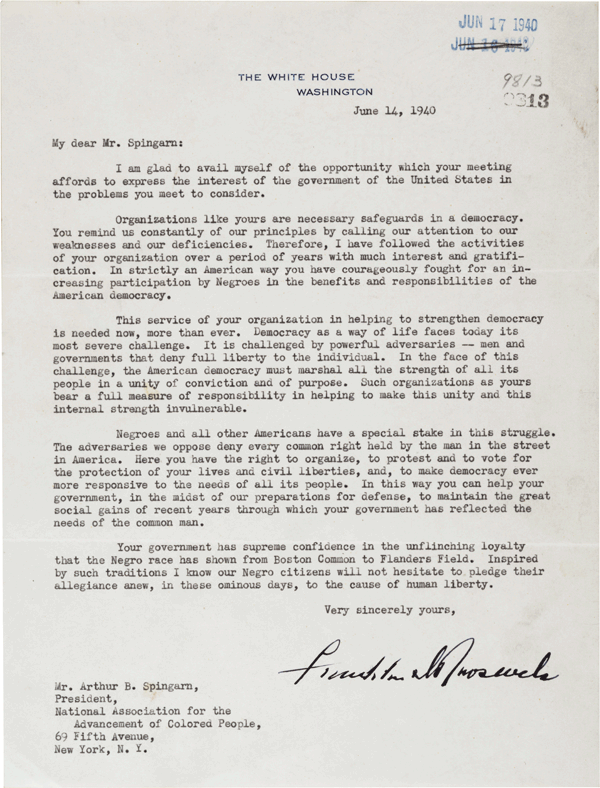

In June 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to NAACP president Arthur B. Springarn, seeking support in the event of war. Though the US would not enter the war until December 1941, the letter demonstrates that President Roosevelt was already anticipating American involvement. In his appeal to the NAACP, he praises the "unflinching loyalty" of African Americans in wars "from Bunker Hill to Flanders Field," and, looking forward, expresses his expectation that the African American community "will not hesitate to pledge their allegiance anew, in these ominous days, to the cause of human liberty."

In June 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to NAACP president Arthur B. Springarn, seeking support in the event of war. Though the US would not enter the war until December 1941, the letter demonstrates that President Roosevelt was already anticipating American involvement. In his appeal to the NAACP, he praises the "unflinching loyalty" of African Americans in wars "from Bunker Hill to Flanders Field," and, looking forward, expresses his expectation that the African American community "will not hesitate to pledge their allegiance anew, in these ominous days, to the cause of human liberty."

The letter, in calling for unity against a common enemy, positions Nazi Germany as a threat to the American values of democracy, civil liberties, and human rights. However, many African Americans saw a stark contrast between these American ideals and the reality of racism. Poet Langston Hughes noted that when Americans decried the human rights injustices of the Nazis, "to a Negro, they might just as well have been speaking of white Southerners in Dixie." Those who joined the war effort often faced discrimination from fellow Americans. One African American soldier, turned away from a Kansas lunchroom that readily served German prisoners of war, realized that "the people of Salina  would serve these enemy soldiers and turn away black American GIs."

would serve these enemy soldiers and turn away black American GIs."

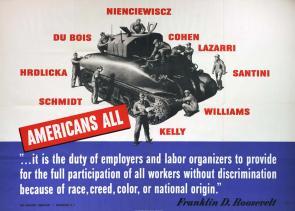

Once the war began, African Americans supported the national war effort while also pushing for more rights at home, a balancing act that one newspaper dubbed the "Double V" campaign: "Victory at home, Victory abroad." The wartime rhetoric that celebrated American democracy and equality, as well as the growing need for soldiers and factory workers, gave African Americans an opportunity to organize for and achieve several civil rights victories, such as an Executive Order banning discrimination in the defense industries. These gains, and the tactics through which they were achieved, lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement of the postwar era.