Black Lives in the Founding Era News, Week 6: Crispus Attucks

Posted by Gilder Lehrman Staff on Wednesday, 04/21/2021

The Gilder Lehrman Institute initiative “Black Lives in the Founding Era” restores to view the lives and works of a wide array of African Americans in the period 1760 to 1800, drawing on our archive of historical documents and our network of scholars and master teachers.

Highlighted in this weekly news post are programs, resources, and other matter related to Black Lives in Founding Era.

Black Lives in the Founding Era News, Week 6

In his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King Jr. writes of Black schoolchildren knowing, beyond what is written in their textbooks, that “the first American to shed blood in the revolution that freed his country from British oppression was a Black seaman named Crispus Attucks.”

Abolitionist leaders lauded Crispus Attucks in the 1840s as a martyr and a hero, a formerly enslaved man who escaped to make a life for himself as a ropemaker and a sailor in Boston, a fierce patriot who hated the British, and the first person to die in the Boston Massacre of 1770.

Abolitionist leaders lauded Crispus Attucks in the 1840s as a martyr and a hero, a formerly enslaved man who escaped to make a life for himself as a ropemaker and a sailor in Boston, a fierce patriot who hated the British, and the first person to die in the Boston Massacre of 1770.

Crispus Attucks was one of five men shot by British soldiers on March 5, 1770. He was honored alongside his four fellow victims in a procession organized by Samuel Adams that transported their caskets to Boston’s Faneuil Hall. After Attucks had lain in state for three days, more than half of Boston’s population walked with the caskets to see them buried in the graveyard.

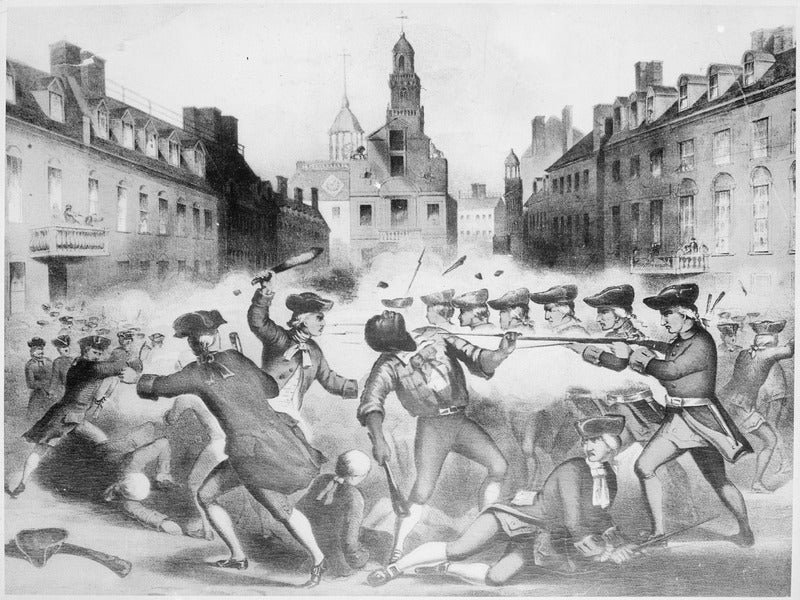

Paul Revere created an engraving of four of the five coffins bearing the victims’ initials that decorated an obituary published as a broadside. More lasting was Revere’s iconic engraving of the scene of the Boston Massacre, in which Attucks is depicted after being shot. While some versions of Revere's engraving change the race of Attucks, who was of mixed African and American Indian descent, the Gilder Lehrman Collection has an original engraving that clearly shows Attucks as a man of color.

Later artistic depictions of Crispus Attucks visually center his martyrdom for the sake of emphasizing his sacrifice and bravery as an African American man who put himself at significant risk—not only for his life but for his freedom—in challenging British soldiers.

Later artistic depictions of Crispus Attucks visually center his martyrdom for the sake of emphasizing his sacrifice and bravery as an African American man who put himself at significant risk—not only for his life but for his freedom—in challenging British soldiers.

Attucks was only one of many Black patriots whose efforts were occasionally recognized in their own times but who have since become inspirations for future generations.

Military historian Michael Lee Lanning wrote in his Fall 2016 History Now article, “African Americans in the Revolutionary War,”

Military historian Michael Lee Lanning wrote in his Fall 2016 History Now article, “African Americans in the Revolutionary War,”

On March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks, an escaped slave, was at the center of what became known as the Boston Massacre that fanned the flames of revolution. Once the rebellion began, Prince Estabrook, another African American, was one of the first to fall on Lexington Green in Massachusetts on April 19, 1775. Other Black men fought to defend nearby Concord Bridge later in the day.

Read more of his essay here.

Learn more about Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre and his depiction of Crispus Attucks here.