Phillis Wheatley, a "Genius in Bondage"

by Vincent Carretta

Who would have guessed that the little girl who arrived aboard a slave ship at Boston on July 11, 1761, would soon become the most celebrated author of African descent in the British empire while she was still a teenager? She was born around 1753 in West Africa, probably somewhere between present-day Gambia and Ghana. [1] The Boston merchant John Wheatley, a transatlantic trader, purchased her to be a domestic servant for his wife, Susanna, and their eighteen-year-old twins, Mary and Nathaniel. Her new owners renamed the child Phillis after the vessel that had brought her from Africa to America, and Wheatley after themselves.

Who would have guessed that the little girl who arrived aboard a slave ship at Boston on July 11, 1761, would soon become the most celebrated author of African descent in the British empire while she was still a teenager? She was born around 1753 in West Africa, probably somewhere between present-day Gambia and Ghana. [1] The Boston merchant John Wheatley, a transatlantic trader, purchased her to be a domestic servant for his wife, Susanna, and their eighteen-year-old twins, Mary and Nathaniel. Her new owners renamed the child Phillis after the vessel that had brought her from Africa to America, and Wheatley after themselves.

As an ardently evangelical Christian, Susanna Wheatley believed that Phillis should be taught to read the Bible. The little girl quickly proved to be a child prodigy, writing her first poem in 1765. Her enslavers undoubtedly believed that her piety and talent reflected well on their own piety and generosity. Susanna Wheatley, the first in Phillis’s network of women patrons and supporters, used her own evangelical connections to enable Phillis to have her first published poem appear in a Rhode Island newspaper in 1767. The publication in Boston and London in 1770 of her single-sheet funeral elegy on the death of the English evangelist George Whitefield gained Phillis Wheatley transatlantic recognition and acclaim. She boldly addressed and sent the poem to Whitefield’s English patron, Selina Shirley Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

Phillis Wheatley had written enough poems by 1772 to warrant seeking a publisher for a volume of her works. Whether by necessity or choice, her book was not published in Boston, but rather in London. She went there with Nathaniel Wheatley in late spring 1773 to arrange for the promotion and publication of her book. Phillis Wheatley’s six-week stay in London was a turning point in her personal and professional lives. Benjamin Franklin was among the many notable people she met during her visit. Having gone to England as an enslaved African Briton, she returned to the colonies prepared to embrace the free African American identity that the American Revolution soon made available to her. Phillis probably agreed to return to Boston only if her owners promised to free her, as she told a correspondent, “at the desire of my friends in England.” [2] The year before she visited London, the Earl of Mansfield had ruled from the King’s Bench in the Somerset case that no slave brought to England from its colonies could legally be forced to return to them as a slave. The ruling’s implications had been well publicized in Boston before Wheatley’s departure to London, and the person who had brought the case before Mansfield was her London tour guide, Granville Sharp. Phillis Wheatley could not legally have been forced back to the colonies. In effect, the choice of freedom, the terms, and the place were hers to make. Her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, dedicated to the Countess of Huntingdon, was published in September 1773, while she was sailing back to Boston. She was freed within weeks of her return.

Although Phillis continued to live with her former owners until John Wheatley’s death in March 1778 (Susanna Wheatley died in March 1774), the practical effects of her liberation were immediate. Freedom gave Wheatley agency, the ability to act on her own behalf. But emancipation also gave her new responsibilities. Life was especially precarious for anyone trying to live by his or her pen during the eighteenth century. She overestimated by a few months how soon copies of her book would be sent from London to Boston. Her concern for protecting its profits reveals a young woman of extraordinary business acumen. Wheatley’s surviving letters display a familiarity with the business of bookselling and the need for authentication that demonstrate how actively she marketed her works. She autographed copies because she anticipated that although pirated editions would demonstrate the popularity of her work, they would cost her profits. She also had the foresight to send a copy of her freedom papers to the agent representing Massachusetts in London to secure both her future earnings and her liberty.

Much about Phillis Wheatley’s later life remains a mystery. She moved to Providence, Rhode Island, during the 1775–1776 British occupation of Boston. She continued to write and manage her own business affairs until she married John Peters, a free man, in Boston on Thanksgiving Day, 1778. They apparently began living together soon after John Wheatley’s death eight months earlier. Phillis Wheatley’s future looked bright in 1778. Phillis and her husband seemed to be relatively prosperous. She sought subscriptions for a new book in 1779, which was to include her correspondence as well as poems, and to be dedicated to Franklin.

But Phillis’s proposed second book never appeared. She and John Peters disappeared from the public records between 1780 and 1784. They probably fled Boston to avoid his prosecution for debt. His creditor had him arrested when they returned during the general economic depression that followed the war. John Peters, like many of his contemporaries in the postwar United States, juggled several occupations to try to remain solvent. He practiced law, as well as medicine, and styled himself a gentleman. But he was likely incarcerated for debt when Phillis died on December 5,1784, perhaps from the “Asthmatic complaint” that had afflicted her during previous winters. [3] Phillis and John Peters apparently had no children. John Peters tried unsuccessfully to publish Phillis’s proposed, but now lost, second volume before he died in Charlestown, Massachusetts, just north of Boston, in March 1801.

Phillis Wheatley has a strong claim to being a founding mother of the United States and its fundamental ideals. Her public anti-slavery stance became far more overt once she was free than it had been while she was enslaved. Religion had originally given her the means and motive to exercise her voice. Freedom gave her the opportunity to use her voice for political ends as well. Her letter to the American Indian Presbyterian minister Samson Occom denouncing slave owners as “Modern Egyptians” was widely reprinted in newspapers in March 1774 throughout British North America, including Canada. Wheatley increasingly came to believe that the colonial struggle for freedom from Britain would lead to the end of slavery in the former colonies. From her elegy on Whitefield on, she offered herself as a kind of national spokesperson. In her poem “To His Excellency General Washington,” Wheatley endorsed the revolutionary cause in late 1775. But she also used her authority to chastise the self-styled freedom fighters for their hypocrisy. In her 1778 poem “On the Death of General Wooster,” Wheatley ventriloquizes Wooster’s voice to exclaim, “But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find/Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—/While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace/And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?”

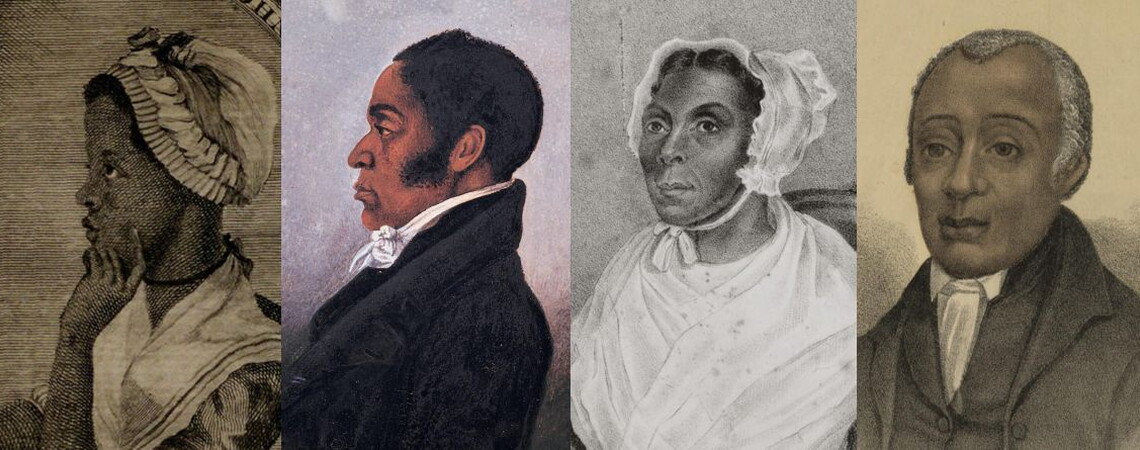

Wheatley, the first person of sub-Saharan African descent to publish a book, became an international celebrity, earning the praise of such contemporaries as George Washington and Voltaire. She also established the literary tradition of English-speaking authors of African descent. Although Wheatley never met her contemporaries Jupiter Hammon, an enslaved African American poet, Philip Quaque, an African-born Christian missionary to Africa, or Ignatius Sancho, a renowned contemporaneous African British author, they all knew of her and her writings. Sancho calls her a “Genius in Bondage.” [4] W. E. B. Du Bois calls her the “pioneer” in the tradition of African American literature. [5] Contemporary African American authors, particularly women such as Nikki Giovanni, Amanda Gorman, June Jordan, and Alice Walker, acknowledge the influence on their own careers and works of Phillis Wheatley Peters. The literary status of that formerly enslaved little girl is undisputed today.

Vincent Carretta is emeritus professor of English at the University of Maryland. He is the author of Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man (2005), The Life and Letters of Philip Quaque, The First African Anglican Missionary (2010), co-edited with Ty M. Reese, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (2011), and a scholarly edition of the writings of Phillis Wheatley (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[1] On Wheatley’s life and times, see Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011). See also Phillis Wheatley, The Writings of Phillis Wheatley, ed. Vincent Carretta (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[2] Phillis Wheatley, Letter to David Wooster, October 18, 1773.

[3] Phillis Wheatley, Letter to Rev. Samuel Hopkins, February 9, 1774.

[4] Ignatius Sancho, Letter to Jabez Fisher, January 27, 1778.

[5] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Negro in Literature and Art,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (1913), in W. E. B. Du Bois, Writings, ed. Nathan Huggins (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1986), 863.