Not the Framers’ Electoral College

by Carolyn Renée Dupont

In one of his essays on the US Constitution, Alexander Hamilton explained the odd mechanism of the Electoral College. The people would choose “judicious” proxies to select the president. These wise sages would cast their votes in a hermetically sealed environment, where they could not “be tampered with.” The whole process would remain free of “cabal, intrigue and corruption.” Surely, Hamilton thought, this plan would repeatedly settle the office of president on the best person.[1]

In one of his essays on the US Constitution, Alexander Hamilton explained the odd mechanism of the Electoral College. The people would choose “judicious” proxies to select the president. These wise sages would cast their votes in a hermetically sealed environment, where they could not “be tampered with.” The whole process would remain free of “cabal, intrigue and corruption.” Surely, Hamilton thought, this plan would repeatedly settle the office of president on the best person.[1]

But the Electoral College has never operated in the pristine way that Hamilton envisioned. The pressure of political operators, custom, state laws, and one constitutional amendment have altered it considerably over the past 235 years. Indeed, today’s Electoral College little resembles the system described in Article II of the Constitution. Rather than a proxy election by wise and discerning persons, today’s Electoral College works simply as an algorithm that distorts Americans’ votes.

The framers created the Constitution before political parties arose. When deeply hostile parties emerged within five years of ratification, they exploited openings in the Electoral College for partisan gain.

Methods of elector selection in the states offered ways to shape election outcomes. The Constitution does not prescribe how electors must be chosen, and states used a variety of methods. In early presidential contests, state legislatures often appointed electors. But popular selection of electors also left room to maneuver. States might opt for the general ticket—winner-take-all, in today’s parlance. Alternatively, states could use the district method, dividing the state into districts and allowing voters in each district to select a single elector.

These methods—legislative appointment, winner-take-all popular vote, or district method popular vote—conferred various partisan benefits, depending on the political landscape. Legislative appointment of electors guaranteed that electors would choose the candidate of the party in control. Popular selection of electors under winner-take-all gave voters a role, but also allowed the dominant party to sweep all the electors for their candidate. The district method meant that a state’s political minority could win electors in their regional pockets of strength. Many people regarded the district method as the most fair and democratic, because it gave a state’s minority party at last a few electors.

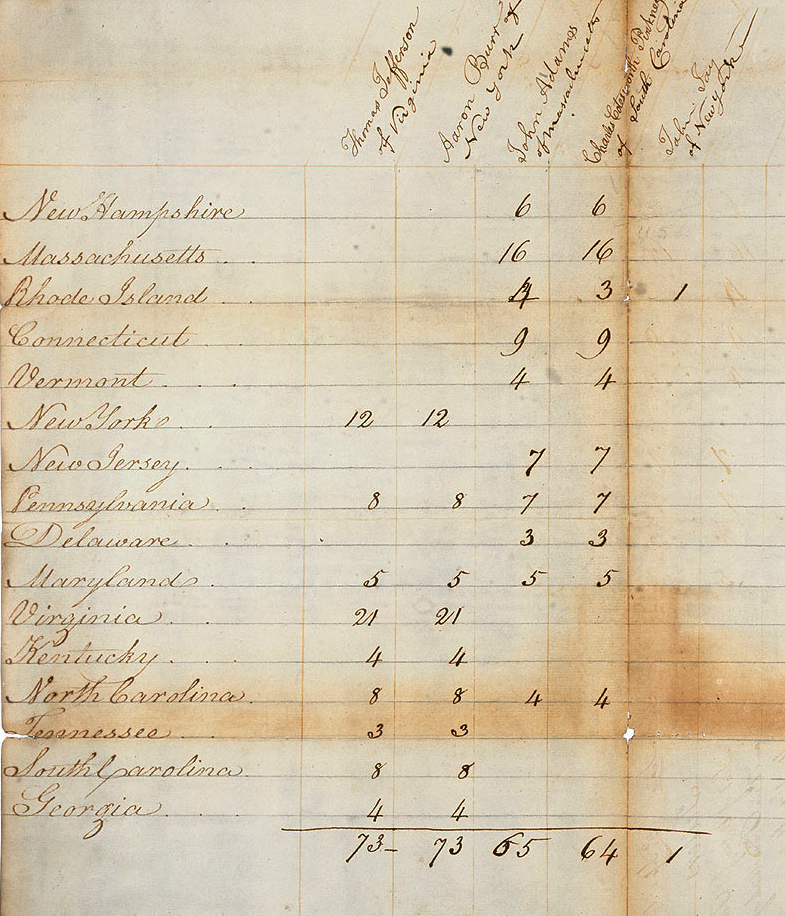

Until 1836, changing political fortunes prompted state legislatures to switch among these methods, sometimes frequently and often barely in time for the election. Massachusetts changed elector selection methods seven times in the first ten presidential contests. One-third of the states switched methods during the rancorous contest between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in 1800. In New Jersey in 1812, the legislature took elector selection away from the voters and placed it in their own hands, only days before the election.[2]

Leaders made these adjustments for obvious political purposes. Virginia, for example, consistently used the district method. But a single Virginia elector voted for John Adams in 1796 and thus helped defeat the home-state candidate Thomas Jefferson (he lost by only three electoral votes.) Determined that Jefferson would get all twenty-one of Virginia’s electors in the next cycle, James Madison pushed a winner-take-all law through the Virginia General Assembly.[3]

Another significant innovation altered the Electoral College. The framers imagined electors as people of wisdom and discernment. In Hamilton’s words, voters would select persons “capable of analyzing the qualities” of the potential candidates. These electors would make a real choice, not transfer votes or register a pre-determined outcome.

But political parties compromised this aspect of the Electoral College as well. As intense and bitter partisanship seized the young United States, elector candidates pledged their loyalty in advance, and voters knew exactly how they would cast their ballots. This practice, fully in place by the first decade of the nineteenth century, rendered elector judgement moot—electors showed up with their “discernment” already pledged. They were party loyalists, rather than wise proxies.

Switching elector selection methods and pledging to candidates in advance profoundly transformed the workings of the Electoral College. At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Rufus King had served on the committee that designed the Electoral College. Thirty years later, as US senator from New York, King confirmed that presidential elections had departed profoundly from the framers’ vision: “The election of a President of the United States is no longer that process which the Constitution contemplated.”[4]

Switching elector selection methods and pledging to candidates in advance profoundly transformed the workings of the Electoral College. At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Rufus King had served on the committee that designed the Electoral College. Thirty years later, as US senator from New York, King confirmed that presidential elections had departed profoundly from the framers’ vision: “The election of a President of the United States is no longer that process which the Constitution contemplated.”[4]

Others with deep knowledge of the Constitution understood the far-reaching nature of these changes. In his 1825 commentary on the Constitution, William Rawle identified the great consequences of these alterations. Electors, he noted, no longer “assemble in their several states for a free exercise of their own judgments, but for the purpose of electing the particular candidate who happens to be preferred by the predominant political party.” Thus, he went on, “the whole foundation of this elaborate system is destroyed.”[5]

Widespread dissatisfaction with Electoral College operations produced a significant effort to reform it in the early 1800s. This movement aimed to make the district method of elector selection universal and permanent. This change would fix elector selection on the most representative method and halt the constant switching. As the author of the Electoral College plan adopted by the Constitutional Convention, James Madison claimed that the framers always had district elections in mind.[6]

Alexander Hamilton believed district elections would “let the Federal Government rest as much as possible on the shoulders of the people, and as little as possible on those of the State Legislatures.” In 1802, he drafted a constitutional amendment with provisions for both district elections and separate, designated votes for president and vice president (an alteration from the original plan, in which the vice-presidency went to the second highest vote-getter.) Though the amendment passed the House, the Senate approved only the portion on designation. In 1804, the states ratified this measure as the Twelfth Amendment.[7]

But the fight for district elections continued, with the support of key American leaders. Thomas Jefferson approved the move because it would put “the choice of President effectually in the hands of the people.” Four times between 1813 and 1822 a constitutional amendment requiring district elections passed the Senate. Each time the amendment failed in the House, but in 1821 it came only six votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority. Yet even as reformers in Congress continued to press for this change, the states succumbed to pressure in the other direction. By 1836, all but one state adopted the less democratic and less representative winner-take-all system.[8]

One twentieth-century alteration finalized the Electoral College’s metamorphosis. Before 1920, ballots always showed electors’ names. Usually, these names appeared in columns underneath the presidential candidate or party to whom they were pledged. Either way, voters selected electors, not presidential candidates. In states with many electors, the process of checking thirty or forty names produced tedium and error.

States solved this problem and promoted efficiency by adopting the short ballot, which listed only the presidential and vice-presidential candidates. Accompanying the short ballot, state laws stipulated that a vote for a candidate equaled a vote for that candidate’s electors. Today, most states also grant the Democratic and Republican Parties the ability to choose electors for their party and thirty-eight states require these electors to vote for the party’s nominee.

These modifications have conclusively destroyed elector discretion and discernment. These laws—and voter expectations—forbid electors from exercising that very wisdom the framers believed qualified an elector.

Today’s electors serve no real purpose. They are party loyalists, legally bound to register a foregone conclusion, and voters rarely even know their names. This reality, in company with the widespread adoption of winner-take-all, has rendered the Electoral College merely an algorithm that distorts Americans’ votes, weighting some heavily and taking no account of others. Today we elect our presidents with this algorithm, given to us by political power ploys, not principled commitments.

For Further Reading

Dupont, Carolyn Renée. Distorting Democracy: The Forgotten History of the Electoral College—And Why it Matters Today. Essex, CT: Prometheus Books, 2024.

Edwards, George. Why the Electoral College is Bad for America. 3rd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019.

Keyssar, Alexander. Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020.

Carolyn Renée Dupont is professor of American history at Eastern Kentucky University. She is the author of Distorting Democracy: The Forgotten History of the Electoral College—And Why It Matters Today (Prometheus Books, 2024).

[1] Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 68, in The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser, March 12, 1788, repr. Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0218.

[2] In Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), Alexander Keyssar offers a good description of chronic switching between elector selection methods.

[3] Madison’s initiative to back a general ticket law in Virginia in 1800 is ably described in Richard Beeman, The Old Dominion and the New Nation, 1788‒1801 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1972), 212‒222. See also Charles Pinckney to James Madison, September 30, 1799, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-17-02-0175.

[4] “Rufus King, Amendment to the Constitution, Senate” (March 20, 1816), in The Founders’ Constitution, Volume 3, Article 2, Section 1, Clauses 2 and 3, Document 9 (University of Chicago Press, web edition), http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a2_1_2-3s9.html; 29 Annals of Cong. 223‒224 (1816).

[5] William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States of America, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Nicklin, 1829), p. 22, repr. “William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States 57–59 1829 (2nd ed.),” in The Founders’ Constitution, Volume 5, Amendment XII, Document 8 (University of Chicago Press, web edition), http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendXIIs8.html.

[6] James Madison to George Hay, August 23, 1823, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/04-03-02-0109.

[7] Alexander Hamilton to James A. Bayard, April 6, 1802, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0315; 11 Annals of Cong. 191 (1802).

[8] Thomas Jefferson to Robert Seldon Garnett, February 14, 1824, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-4052. Keyssar, 66‒93, describes the battle to pass a constitutional amendment requiring district elections.