A frightening mission over Iwo Jima, 1945

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Robert L. Stone

Lieutenant Bob Stone served as a bombardier in the 431st Bomb Squadron (Heavy), 7th United States Army Air Force in the Pacific. This Spotlight is part of a series of documents detailing the experience of airmen in World War II. Click here for more information about Bob and to read more in this series.

Soldiers rarely describe the details of battles in letters. During World War II, the discussion of events was prohibited by the military and censors were quick to remove anything they considered a risk to the safety and security of the troops. In addition, putting frightening details of war into writing would only worry loved ones at home.

In February 1945, Lieutenant Bob Stone wrote to his parents on his way back to duty from leave in Hawaii. In this lengthy letter, he only briefly mentions a mission on which “all of us were pretty badly scared.” It is also apparent that while he was able to call his parents while on leave, he chose not to tell them details of that mission.

For more than sixty years, Bob did not speak about his war service. In 2006, eleven-year-old Otis Baker asked Bob about his role in the war. As the conversation progressed, Otis decided to write a research paper for school based on Bob’s experience. Bob dictated an oral history to Otis that documented the reality of battle in detail. In his oral history, Bob finally spoke about the terrifying close calls he wrote home about in February 1945.

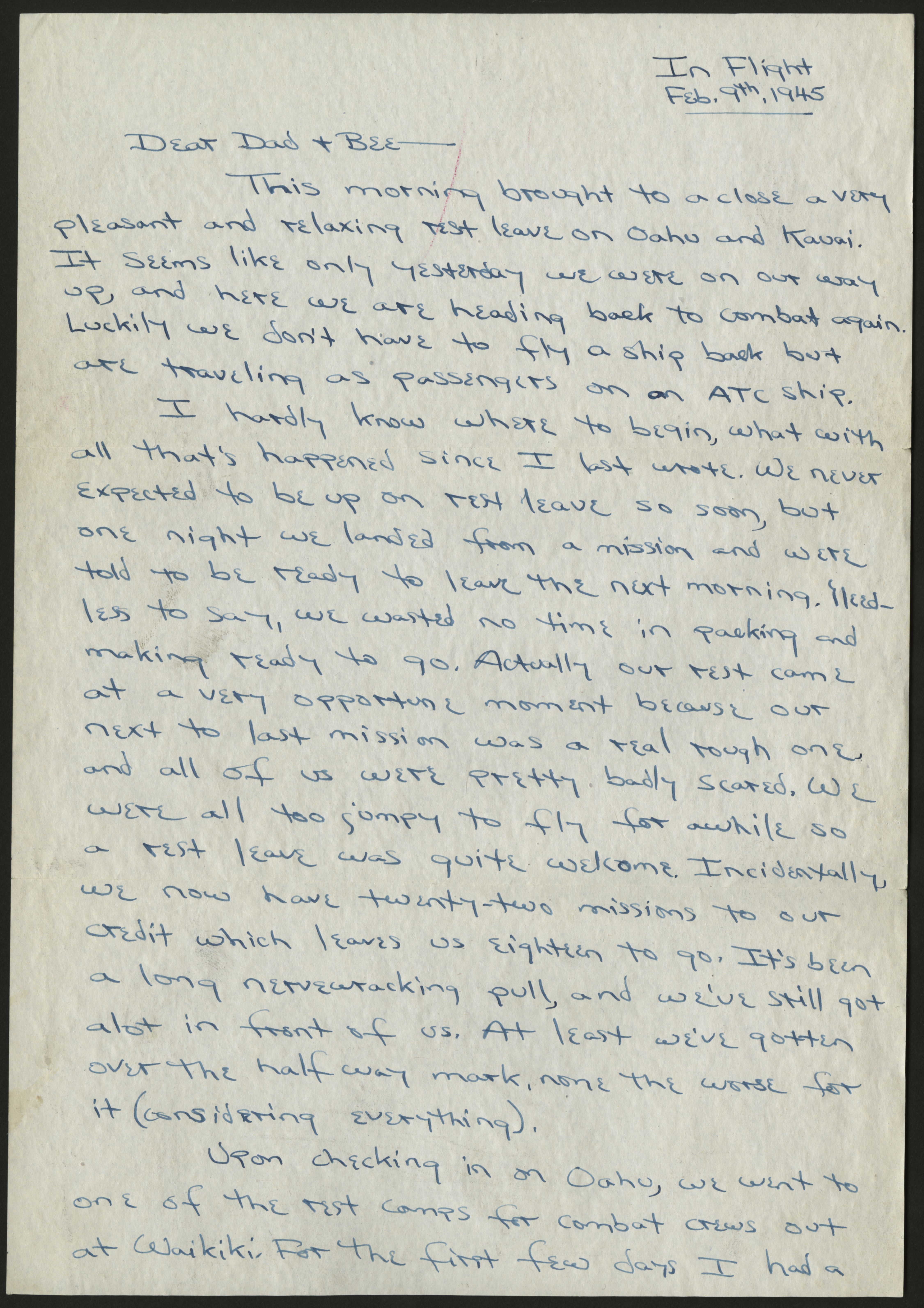

Excerpt from a letter from Robert L. Stone to Jacob Stone and Beatrice Stone, February 9, 1945

Excerpt from a letter from Robert L. Stone to Jacob Stone and Beatrice Stone, February 9, 1945

I hardly know where to begin, what with all that’s happened since I last wrote. We never expected to be up on rest leave so soon, but one night we landed from a mission and were told to be ready to leave the next morning. Needless to say, we wasted no time in packing and making ready to go. Actually our rest came at a very opportune moment because our next to last mission was a real rough one and all of us were pretty badly scared. We were all too jumpy to fly for awhile so a rest leave was quite welcome. Incidentally, we now have twenty-two missions to our credit which leaves us eighteen to go. It’s been a long nervewracking pull, and we’ve still got alot in front of us. At least we’ve gotten over the half way mark, none the worse for it (considering everything) . . . .

Arranged for a couple of phone calls which always involve red tape; censorship, and lots of time. I can’t tell you how good it was to talk to you and hear your voices again. Trans-pacific calls are always a real thrill for me—a treat that I’d like to enjoy more often.

Excerpt from Bob Stone’s oral history as dictated to Otis Baker and Sheila Stone, 2006. Printed in Letters in a Box: Handwritten by Robert L. Stone, during World War II, ed. Sheila M. Stone (2015), 398-399.

We had just bombed Iwo Jima and were leaving the target, which was 6 hours away from our base on Guam when several Japanese fighter planes called Zeros attacked us. Although we fought them off, we took a number of hits, as well as some hits from the thick flak we encountered when we flew over the island to drop our bombs. After a while flying back towards Guam, one of our four engines sputtered and stopped running. The pilot "feathered" this engine which means that he turned the propeller blades sideways so that they would cut through the air rather than being a total drag. A loaded B-24 cannot take off with only two working engines, but once in the air it can fly with only two engines.

With only three engines operating, the plane was flying much slower and was beginning to lose altitude, which made us consume more gasoline. All of a sudden there was total silence when all three engines stopped.

The silence was devastating and eerie.

We were all in a state of panic wondering what had happened and if the end was near—it seemed inevitable! After what seemed like a long time, but probably was only a couple of minutes, the engines caught hold and we were once again on our way to our base. We found out that in transferring fuel from the non-working engine to the working ones, an air lock developed which momentarily stopped the proper flow of gas and made the plane stall.

Because of our loss of altitude, we decided to lighten our load by throwing overboard anything we could such as the ball turret (which was incredibly heavy), eight very heavy 50 millimeter guns, ten very heavy flak jackets (used for body protection) and a small gas engine used to start the plane's engines. Also, a great many boxes of unused 40-millimeter shells were deep sixed. There may have been more items that I don't recall any longer, but anything of any weight except the Norden Bomb Sight was jettisoned. The bombsight was top-secret equipment, very expensive, and very difficult to replace because it enabled the pilot to transfer the control of the plane to the bombardier who could then zero in on the targets more accurately. The reduction of all this weight helped us maintain altitude and at the same time use less gas. We continued along for about another hour or so hoping we would not lose altitude and not use up all our gas before we got to base. We also hoped that our three engines would continue to operate until we landed safely.At this point, we decided to head to Saipan rather than our home base of Guam because Saipan was somewhat closer than flying back to Guam. With less than two hours left to reach Saipan, another engine conked out and had to be "feathered" leaving us with only two working engines—happily one on each wing. Now our big worry was whether we had sufficient gas to get to Saipan and whether we could maintain enough altitude to make a landing when we got there. Also, it was critical that the two remaining engines continued to operate properly. The next hour or so was really tense and scary as there was nothing else we could do except to hope that Saint Francis and Saint Christopher would do their job and protect us!

It was an enormous relief when we saw the lights of Saipan. We started our final approach and descent to the runway from a much lower altitude than normal. When the wheels hit the runway, we started to roll but only got half way down the runway when the other two engines stopped because we had completely run out of gas. This was an absolute miracle because if we had to fly another 100 feet to reach the runway we would have come down in the water and crashed! When the crew left the airplane, we all kissed the ground because we had been so fortunate in making it back safely to terra firma! The Flying Jenny was hauled away and never flew again because its engines and the body of the plane had been so badly damaged it was not worth repairing.

On June 5, 1945, Bob was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission. Not only did the crew survive an incredible ordeal, they successfully dropped 100 percent of their bombs on target.