The League of Women Voters: A Century of Voter Engagement

by Barbara Winslow

The League of Women Voters (LWV) was founded in 1920 by American suffragists, just months before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the constitutional right to vote after more than seventy years of struggle. Over the past one hundred years the League, following in the progressive politics of its mother organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), has been an influential and powerful women’s coalition. An activist, grassroots organization, the League believes that citizens should play a critical role in civic advocacy. Its founders believed that maintaining a nonpartisan stance would protect their fledgling organization from becoming mired in the party politics of the day. However, League members were encouraged to be political themselves by educating citizens about, and lobbying for, governmental and social reform legislation. The League’s accomplishments, failures, challenges, and ups and downs reflect the trajectory of US reform politics, class and racial conflicts, and the ebb and flow of women’s and feminist movements.

The League of Women Voters (LWV) was founded in 1920 by American suffragists, just months before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the constitutional right to vote after more than seventy years of struggle. Over the past one hundred years the League, following in the progressive politics of its mother organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), has been an influential and powerful women’s coalition. An activist, grassroots organization, the League believes that citizens should play a critical role in civic advocacy. Its founders believed that maintaining a nonpartisan stance would protect their fledgling organization from becoming mired in the party politics of the day. However, League members were encouraged to be political themselves by educating citizens about, and lobbying for, governmental and social reform legislation. The League’s accomplishments, failures, challenges, and ups and downs reflect the trajectory of US reform politics, class and racial conflicts, and the ebb and flow of women’s and feminist movements.

The genesis of the League was in the West. In 1909, at the NAWSA convention in Seattle, Washington, suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe proposed a national league of women voters. The conference rejected the motion. After Washington State voted to enfranchise women, DeVoe organized the National Council of Women Voters, a nonpartisan coalition of women from voting states. The idea was to create an educational organization of and for women voters to lobby for legislation and campaign for women’s suffrage.[1]

Prior to the 1919 NAWSA convention in St Louis, the association’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt, began negotiating with DeVoe to merge her organization with a new league that would be the successor to NAWSA. As fifteen states had already ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, NAWSA wanted to move forward with a plan to educate women on the voting process and further their participation in the political arena. The merger was officially completed on January 6, 1920. The formal organization of the League of Women Voters was drafted at the February 1920 convention held in Chicago. For one year, the League was a committee of NAWSA before it became its own independent entity.

Prior to the 1919 NAWSA convention in St Louis, the association’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt, began negotiating with DeVoe to merge her organization with a new league that would be the successor to NAWSA. As fifteen states had already ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, NAWSA wanted to move forward with a plan to educate women on the voting process and further their participation in the political arena. The merger was officially completed on January 6, 1920. The formal organization of the League of Women Voters was drafted at the February 1920 convention held in Chicago. For one year, the League was a committee of NAWSA before it became its own independent entity.

The League was born with a sense of urgency, mission, and apprehensive optimism. Not all NAWSA members supported the formation of the League. Some argued that since NAWSA’s goal of securing the vote was accomplished, NAWSA could be disbanded. Others were concerned that an independent organization of women might create dissension within and take women out of the existing political parties. Others were mindful of the growing conservative climate that was hostile to any form of radicalism, including feminism. Some claimed that the existence of the League would cause conflict between men and women, leading even Catt to assure its membership, “we are not radicals.” [2]

Catt promised that this new organization would be “a living memorial . . . dedicated to the memory of our brave departed leaders, to the sacrifices they made for our cause.” A League, she continued, was necessary so that women could “use their new freedom to make their nation safer for their children and their children’s children. . . . What should be done, can be done; what can be done, let us do.” [3]

Catt promised that this new organization would be “a living memorial . . . dedicated to the memory of our brave departed leaders, to the sacrifices they made for our cause.” A League, she continued, was necessary so that women could “use their new freedom to make their nation safer for their children and their children’s children. . . . What should be done, can be done; what can be done, let us do.” [3]

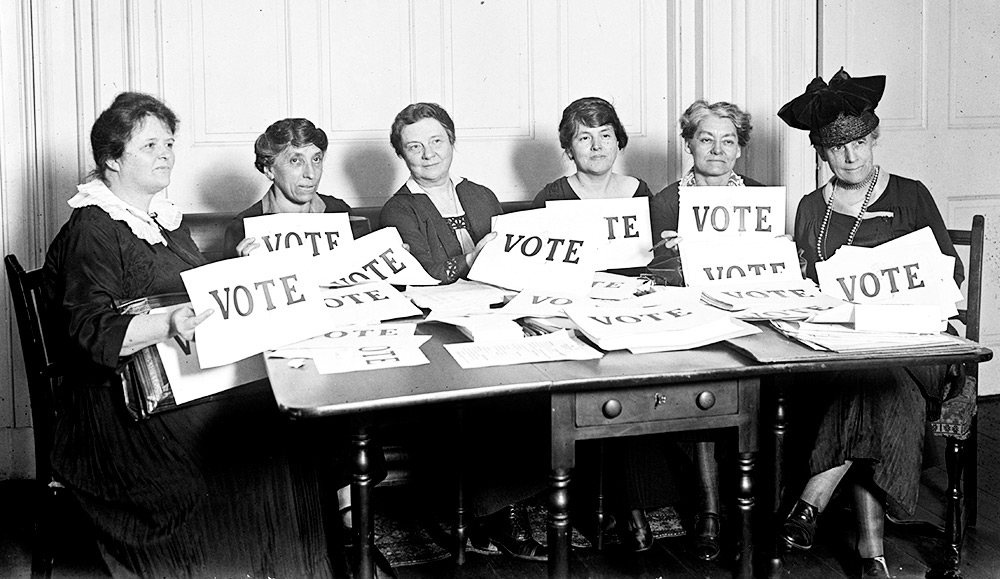

Maud Wood Park was elected the first president of the League. The League’s first major legislative victory was the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, which provided federal funds for maternity and child welfare. The League’s platform was ambitious and progressive, advocating, for example, support for the Cable Act supporting independent citizenship for married women, which became law in 1922, ensuring that a woman’s citizenship did not rely on the status of her husband’s citizenship. The League also sponsored a “get out the vote” campaign and called for legislation supporting collective bargaining, child labor laws, a minimum wage, a state employment service, and compulsory public education. By 1924 there were national branches in 346 of 433 congressional districts.

In the 1920s, the League faced a challenge from a rival feminist organization, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) founded by Alice Paul. In 1923 the NWP introduced an amendment to the US Constitution which read, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” This proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was opposed by the LWV as well as by every progressive, women’s, and trade union organization. The proposed ERA, the League argued, would result in the eradication of women’s protective legislation. This fight over the meaning of equality weakened the women’s/feminist movement and led to the persistent belief that feminism means elitism, intemperance, and ignorance of the needs of poor and working women. [4]

The League continued its progressive legislative agenda throughout the decades. Its membership declined during the 1929−1940 Depression, dropping from 100,000 in 1924 to 44,000 in 1934. The budget was cut in half, necessitating a major reduction in staff and services to branches of the League. But the League remained committed to progressive legislation, supporting most of the policies and proposals initiated by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

From its inception, the League was internationalist. Its founding members had been involved in a wide range of global suffrage, temperance, peace, and social welfare organizations. In the 1920s the LWV supported the League of Nations. In the 1930s it warned of the dangers of fascism, supported Roosevelt’s Lend Lease, the war aims of World War II, and, postwar, the United Nations. Harry Truman invited the League of Women Voters to serve as a consultant to the US delegation at the United Nations Charter Conference in 1945. To this day, the League maintains its presence at the United Nations through its one official and two alternate observers.

However, on the issue of race, the League’s record was shameful. Following in the tradition of the woman suffrage organizations, the League supported racial segregation. NAWSA and the NWP never challenged the denial of voting rights to African American men or racial segregation in the South, and they took their racism into the LWV. Southern state chapters had white-women-only membership requirements. In fact, the League’s membership was overwhelmingly white, privileged, college educated, and married. Fewer than twenty-five percent of the members worked outside the home. Very few women of color could be found in any League chapter. The tiny number of African American League members came from the historically black colleges and universities. [5]

In the post–World War II era, the League began to make serious changes in its activities and policies. The civil rights, women’s, and social justice movements galvanized the League’s reassessment. As early as the 1950s state chapters began to challenge restrictive voter registration laws. While much attention has been given to the racist voting laws in the southern states, northern states’ voter laws were also reprehensibly restrictive. In the 1950s the New York State League of Women Voters mounted a campaign called Permanent Personal Registration (PPR) to make voter registration easier. The New Yorker described this campaign as “the greatest political effort since the fight for woman’s suffrage.” [6] As of 1960, in New York State one had to pass an English written and oral literacy test and provide proof of an eighth-grade education. The League fought against these racist and xenophobic restrictions.

The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka forced the League and its state chapters to take a stand on racial discrimination. The Georgia League dropped its white-women-only membership requirement in 1956. White women left the chapter, but four African American women joined in Atlanta. Four years later, the GALWV supported school desegregation, but only if it was voluntary. By 1964 southern leagues supported desegregation and black voter rights. [7]

The postwar women’s movement changed the League’s membership and political direction. It had to compete for members and political influence with organizations such as the National Organization for Women (NOW). The League reversed its position on the ERA and, after 1974, became a major partner with NOW in championing the amendment. The LWV sponsored the United States presidential debates in 1976, 1980, and 1984, but pulled out in 1988 after refusing to go along with the demands of the major candidates’ campaigns. The League continues to provide voters with nonpartisan information about federal, state, and local candidates as well as information on the political issues of the day. [8]

The League’s membership has tripled since 2016; it now has more than 500,000 members in approximately 700 state and local organizations. It is still overwhelmingly white and middle class, but more working women are members. Especially in urban areas, the League chapters make attempts at diversity. While still nonpartisan, the League champions a very progressive agenda including support for reproductive rights, gun safety, abolition of the death penalty, universal health care, childcare, enforcement of the EPA, and legislation combating climate catastrophe; it opposes racial profiling and economic, racial, and gender inequality. The League is also committed to universal suffrage. It opposes voter suppression in any and all forms, Citizens United, and gerrymandering; it supports federal legislation guaranteeing every eligible voter the right to vote as well as voting rights for those incarcerated and for those out of prison. While it is a very different organization today than the one founded in 1920, the twenty-first-century League of Women Voters has fulfilled much of its century-old mission.

Selected Bibliography

Cashin, Maria Hoyt. Sustaining the League of Women Voters in America. Washington DC: New Academia Publishing, 2013.

League of Women Voters website, https://www.lwv.org/.

Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer M.Winning the West for Women: The Life of Suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.

Stevens, Jennifer A. “Feminizing Portland, Oregon: A History of the League of Women Voters in the Postwar Era, 1950−1975,” in Kathleen A. Laughlin and Jacqueline L. Castledine, eds., Breaking the Wave: Women, Their Organizations, and Feminism, 1945−1985 , New York: Routledge, 2011.

Van Voris, Jacqueline. Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life. New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1987.

Susan E. Whitney, Seventy-Five Years Rich: A Perspective on the Woman’s Suffrage Movement and the League of Women Voters in Georgia . Atlanta, GA: League of Women Voters of Georgia, 1995.

Louise M. Young. In the Public Interest: The League of Women Voters, 1920−1970. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989.

[1] See “National Council of Women Voters” on the website of the Washington State Historical Society.

[2] Louise M. Young, In the Public Interest: The League of Women Voters, 1920−1970 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), p. 48; “Looking Forward: Extracts from Mrs. Catt’s Closing Speech [at the St Louis Convention of 1919],” in The Woman Citizen: The Woman’s National Political Weekly, NS vol. 3, no. 46 (April 12, 1919), p. 960; Young, In the Public Interest, p. 34.

[3] “The Nation Calls! Notes from the Speech of Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt, President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Made Monday Evening, March 24, at the Opening of the Convention in St. Louis,” in The Woman Citizen: The Woman’s National Political Weekly, NS vol. 3, no. 44 (March 29, 1919), p. 917.

[4] Alice Paul had been a militant suffragette working with the English Women’s Social and Political Union. (Members of the WSPU called themselves suffragettes. In the US, militants and constitutionalists preferred to be called suffragists.) When she returned to the United States, Paul joined NAWSA, advocating a more confrontational approach in order to win suffrage. She left NAWSA to form the rival and more militant National Woman’s Party. After 1920, the NWP campaigned around a number of women’s equality issues. See Christine Lunardini, Alice Paul: Equality for Women, in Lives of American Women, ed. Carol Berkin (New York: Westview Press, 2013).

[5] Young, In the Public Interest, p. 172. To its credit, the League acknowledges its racist history. The League’s future activities will determine whether or not it lives up to its promises to change. For more, see Virginia Kase, “Facing Hard Truths about the League’s Origin,” https://www.lwv.org.

[6] “They Darned Near Killed Luella,” New Yorker, May 5, 1956, p. 108. This article focuses on the years-long struggle to pass Permanent Personal Registration, focusing mainly on League personnel and dealing with New York State legislators. On a personal note, the Luella profiled was my mother.

[7] Susan E. Whitney, Seventy-Five Years Rich: A Perspective on the Woman’s Suffrage Movement and the League of Women Voters in Georgia (Atlanta, GA: League of Women Voters of Georgia, 1995), pp. 47−92.

[8] The League even has an FBI file. In 1984, the Massachusetts State League brochure included information about the Communist Party presidential slate with Angela Davis as the vice-presidential candidate.

Barbara Winslow is professor emerita of history at Brooklyn College. An authority on women’s activism, she is the founder and director emerita of the Shirley Chisholm Project. She is the author of Clio in the Classroom: A Guide for Teaching US Women’s History (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (Westview Press, 2013). With Julie A. Gallagher, she is the co-editor of Reshaping Women's History: Voices of Nontraditional Women Historians (University of Illinois Press, 2018).