A Second Declaration of Independence: The 1848 Declaration of Sentiments

by Sally G. McMillen

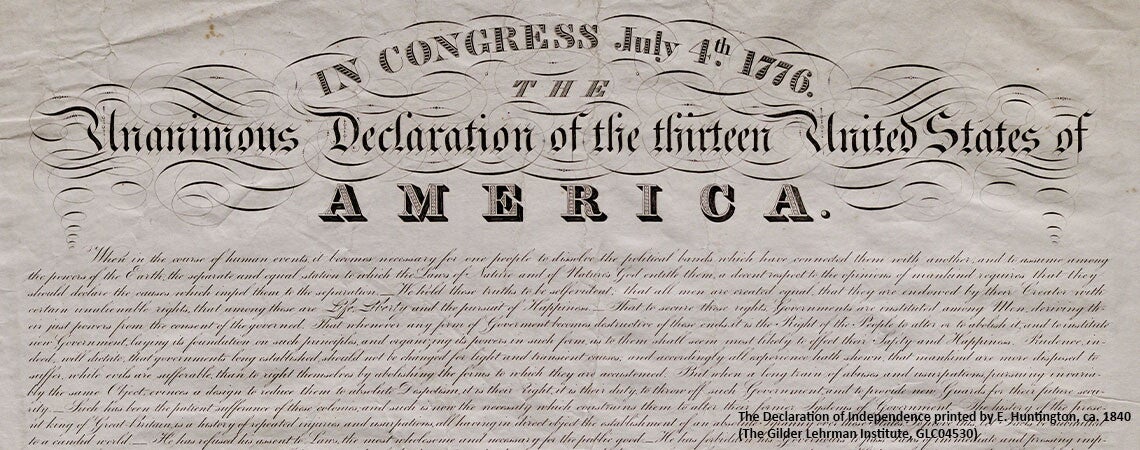

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.[1] Upon casual reading, this phrase should sound familiar. Yet unlike what appeared in our nation’s 1776 Declaration of Independence, the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments offered a significant addition, declaring all women and men to be equal. While few might question that today, nearly 175 years ago, gender equality was considered extremely radical.

The 1848 Declaration of Sentiments was written for an equally radical event. In July 1848 at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York, some 300 men and women assembled to “discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.”[2] The two-day Seneca Falls Convention was the first formal gathering in this country to address women’s oppression and inferior status and offer proposals for change. The Declaration of Sentiments served as the meeting’s centerpiece. From that event began the protracted seventy-two-year struggle for women to win the right to vote.

In mid-nineteenth-century America, the natural order, the nation’s laws, its social structure, and its religious tenets supported the concept that White men held all power in this country. It was an absurd idea that women would desire an equal role, that they would demand all the rights of citizenship and have a voice in the governance and law-making of our nation.

Well before the Declaration of Sentiments was presented and the 1848 meeting convened, a few women challenged their inferior status. In March 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, who was serving in the Second Continental Congress, urging him to “Remember the Ladies,” and hinting at a rebellion if women gained no voice or representation in the new nation.[3] John, of course, ignored his wife, claiming there was no telling what might come next, perhaps women even demanding the right to vote. New Jersey, the only state to do so, allowed women who owned property to vote for a few years. Its 1776 constitution did not exclude women and Blacks from voting until 1807. A bold twosome, Sarah and Angelina Grimké, left their slave-owning family in Charleston, South Carolina, and moved to Philadelphia in the 1820s. There they wrote essays and tracts that urged women in both the North and the South to work to eradicate slavery. The sisters also engaged in behavior unseemly for women, lecturing to mixed audiences of men and women. Massachusetts ministers’ effort to silence them generated angry reactions from a few budding feminists who felt women were truly oppressed. Months later, in 1837, Sarah Grimké penned Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, denouncing women’s inferior status and defending women’s rights. In the 1830s, Maria Stewart, a  Black woman, described the devastating impact racism had on Black women. Also of note were American Indian tribes functioning under a matrilineal structure, inspiring well-known Quaker minister Lucretia Mott and other women. Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845, boldly challenged the idea of separate spheres for men and women and encouraged female self-fulfillment and access to higher education.[4]

Black woman, described the devastating impact racism had on Black women. Also of note were American Indian tribes functioning under a matrilineal structure, inspiring well-known Quaker minister Lucretia Mott and other women. Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845, boldly challenged the idea of separate spheres for men and women and encouraged female self-fulfillment and access to higher education.[4]

The event that prompted the Seneca Falls Convention was a tea party held on July 9 or 10, 1848, hosted by Jane C. Hunt of Waterloo, New York. Attendees included Lucretia Mott, her sister Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a relative newcomer to the area. Their conversation quickly turned to articulating the many insults and instances of exclusion they experienced as women. Their anger intensified. How could this country be a democratic republic when a significant percentage of its population had few, if any, rights, were shunned from the public world, and confined to their separate sphere in the home?

Emboldened by a reform spirit pervading the nation, the five women decided to take action and convene a meeting to address women’s secondary status and present demands for change. The women placed ads in local papers and invited friends and associates to gather on July 19 and 20, 1848, in Seneca Falls, New York.

A few days after the tea party, Stanton traveled to the M’Clintocks’ home with a draft of a Declaration of Sentiments in hand. There, she, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and the M’Clintocks’ daughter Elizabeth struggled to transform that draft into a stirring document. What they did that was so “inspired,” according to historian Lori Ginzberg, was to model their writing on a familiar, respected document, the 1776 Declaration of Independence.[5] Like the nation’s founding fathers, they too did not mince words. Replacing England’s King George III as the cause of colonists’ woes, the 1848 Declaration now blamed all men “for a long train of abuses and usurpations.” The Declaration of Sentiments then laid out sixteen complaints or injustices that kept women in a subordinate role.

A few days after the tea party, Stanton traveled to the M’Clintocks’ home with a draft of a Declaration of Sentiments in hand. There, she, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and the M’Clintocks’ daughter Elizabeth struggled to transform that draft into a stirring document. What they did that was so “inspired,” according to historian Lori Ginzberg, was to model their writing on a familiar, respected document, the 1776 Declaration of Independence.[5] Like the nation’s founding fathers, they too did not mince words. Replacing England’s King George III as the cause of colonists’ woes, the 1848 Declaration now blamed all men “for a long train of abuses and usurpations.” The Declaration of Sentiments then laid out sixteen complaints or injustices that kept women in a subordinate role.

Their grievances were broad in scope, covering political, economic, social, religious, and educational issues. Among their complaints:

- Women were not allowed to vote and were excluded from every level of government.

- Men controlled the majority of profitable employments, preventing women from access to respectable, well-paid jobs in law, medicine, and the ministry.

- Single, property-owning women had to pay taxes to a government that did not consider them citizens.

- Women had to obey the nation’s laws though they had no voice in making them.

- A different code of morals dictated male and female behavior, with higher standards demanded of women.

- Women could not attend college as men were doing, all colleges being closed to them.

- Wives could not claim wages they earned or property they brought into a marriage. All their possessions belonged to their husbands.

- Wives had to obey their husbands in all instances, creating a situation of near enslavement.

- In rare cases of divorce, fathers gained custody of their children.

- Men robbed women of their self-confidence and self-respect.

The Declaration then presented eleven resolutions for change. The most radical of these and the one that fostered the greatest debate urged “women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”[6] Several Quakers objected, wanting nothing to do with politics and a government that condoned slavery. Stanton argued otherwise, believing women’s political power would lead to other reforms.  Frederick Douglass, who was present, saved the day, defending the resolution, asserting he, a formerly enslaved Black man, could not support his right to vote without supporting the same for women. Ultimately, all resolutions passed, and 100 attendees, both men and women, signed the document. Lucretia Mott ended with a stirring speech, accurately predicting the road ahead in achieving women’s rights would encounter opposition and ridicule. But she hoped this convention would be “followed in due time by one of a more general character.”[7]

Frederick Douglass, who was present, saved the day, defending the resolution, asserting he, a formerly enslaved Black man, could not support his right to vote without supporting the same for women. Ultimately, all resolutions passed, and 100 attendees, both men and women, signed the document. Lucretia Mott ended with a stirring speech, accurately predicting the road ahead in achieving women’s rights would encounter opposition and ridicule. But she hoped this convention would be “followed in due time by one of a more general character.”[7]

Issues in the Declaration paralleled what many women in this country were experiencing. But one need understand that the document reflected the views of its authors and supporters—mostly middle-class, northern, White reformers. It failed to mention millions of enslaved people in the South and the horrors, cruelty, and sorrows they endured. It ignored American Indian tribes, their forced removal, and their lands confiscated or stolen by Whites. It overlooked poor and farm women who hadn’t the time or energy to ponder, much less fight for women’s rights. And the Declaration contained a couple of errors. Oberlin Collegiate Institute (Oberlin College) had opened in 1833 and admitted women into its bachelor’s degree program in 1837, followed by a handful of other co-ed colleges in the upper Midwest. In 1839, Mississippi enacted the nation’s first Married Women’s Property Act, protecting wives’ assets so families would not descend into poverty if husbands gambled, borrowed excessively, or frittered away fortunes. New York and Pennsylvania enacted married women’s property laws in 1848.

The Seneca Falls Convention generated a brief flurry of interest, with similar, though smaller, meetings held in Rochester, New York, and towns in Indiana and Ohio. In October 1850, the first truly national Women’s Rights Convention met in Worcester, Massachusetts, with more than 1,000 people in attendance, representing several states. Over the next decade, annual women’s rights conventions were held (except 1857) in various northern cities. At the 1854 Women’s Rights Convention, Lucretia Mott urged that the Declaration of Sentiments be adopted as a model to follow. Instead, a committee of five was appointed to draft a new Declaration. It was read at the end of the convention but neither the old nor the new version was adopted.

Despite endless searching, the original 1848 Declaration of Sentiments has never been found. Fortunately, Frederick Douglass published the first known copy of the Declaration in his Rochester newspaper, The North Star, in July 1848.

Even if it never became a permanent model for national women’s conventions, the Declaration of Sentiments is an important, fascinating document. On occasion, women still reference it. Maya Angelou wrote a poem based on it for the 1977 National Women’s Rights Meeting in Houston. Hillary Clinton referred to it in her speech after winning the 2016 Democratic nomination for president. Not only is the Declaration symbolic but it reveals much about women’s status in mid-nineteenth-century America. Women then had every right to complain vociferously and to demand full citizenship and equal treatment. The Declaration is also useful in assessing how far women have come—or not come—since 1848 and whether women in this country today have achieved true equality with men in all areas of life.

Sally G. McMillen is the Mary Reynolds Babcock Professor of History Emerita at Davidson College. She is the author of Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement (Oxford University Press, 2008) and Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life (Oxford University Press, 2015).

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1: 1848–1861 (Rochester, New York: Fowler & Wells, 1889), 70.

[2] Seneca County Courier, July 14, 1848.

[3] Abigail Adams, Letter to John Adams, Braintree, Massachusetts, March 31, 1776.

[4] Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Woman’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 14–15. Tetrault offers a fascinating rethinking of the Seneca Falls Convention, demonstrating how Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony engaged in a campaign to write the origins story, seeking to prove the centrality of their roles, the insignificance of their rivals, and the importance of Seneca Falls in initiating the struggle for women’s rights.

[5] Lori D. Ginzberg, Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009), 58.

[6] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1: 1848–1861 (Rochester, New York: Fowler & Wells, 1889), 72.

[7] Lucretia Mott, Letter to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, July 16, 1848. For details on the Seneca Falls Convention, see Sally G. McMillen, Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008) and Judith Wellman, The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004).