The Education of Women: On This Day, 1735

Posted by Anna Khomina on Friday, 05/19/2017

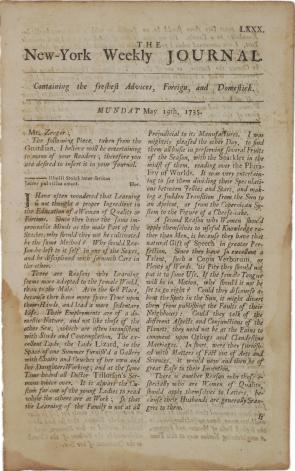

On May 19, 1735, the New-York Weekly Journal republished an article from England’s The Guardian on the reasons to educate women. Most notably, the author (most likely Joseph Addison) states that women, though they have different roles than men, have "the same improvable Minds" by virtue of their status as human beings. "Learning and Knowledge are Perfections in us, not as we are Men, but as we are reasonable Creatures, in which Order, of Beings the Female World is upon the same Level with the Male." The author even argues that women have certain advantages over men in obtaining an education: more spare time, a natural gift for speech, a responsibility for educating their children, and the need to keep busy.

On May 19, 1735, the New-York Weekly Journal republished an article from England’s The Guardian on the reasons to educate women. Most notably, the author (most likely Joseph Addison) states that women, though they have different roles than men, have "the same improvable Minds" by virtue of their status as human beings. "Learning and Knowledge are Perfections in us, not as we are Men, but as we are reasonable Creatures, in which Order, of Beings the Female World is upon the same Level with the Male." The author even argues that women have certain advantages over men in obtaining an education: more spare time, a natural gift for speech, a responsibility for educating their children, and the need to keep busy.

The quality of a woman’s education in 18th- and 19th-century America—even after the spread of free common schools—often rested on the magnanimity of her father or husband, and women who were granted this rare opportunity frequently echoed Addison’s thoughts. Mercy Otis Warren, author of political articles, satires, and verses during the Revolutionary era, explained to a female friend that "the deficiency" of women’s accomplishments "lies not so much in the inferior contexture of female intelligence as in the different education bestowed on the sexes." She accepted her role as a dutiful puritan housewife, but believed "a concern for the welfare of society ought equally to glow in every human heart."

Similarly, Lydia Maria Child, editor of The National Anti-Slavery Standard and one of a growing number of women’s rights advocates, believed that educating women would benefit all of society by creating a happier domestic sphere. "The more women become rational companions," she wrote in an 1843 article, "partners in business and in thought, as well as in affection and amusement, the more highly will men appreciate home."

Learn more about women’s contributions to American history in History by Era.