From the Editor

by Carol Berkin

This issue of History Now is supported by the Veterans Legacy Grant Program, an initiative of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

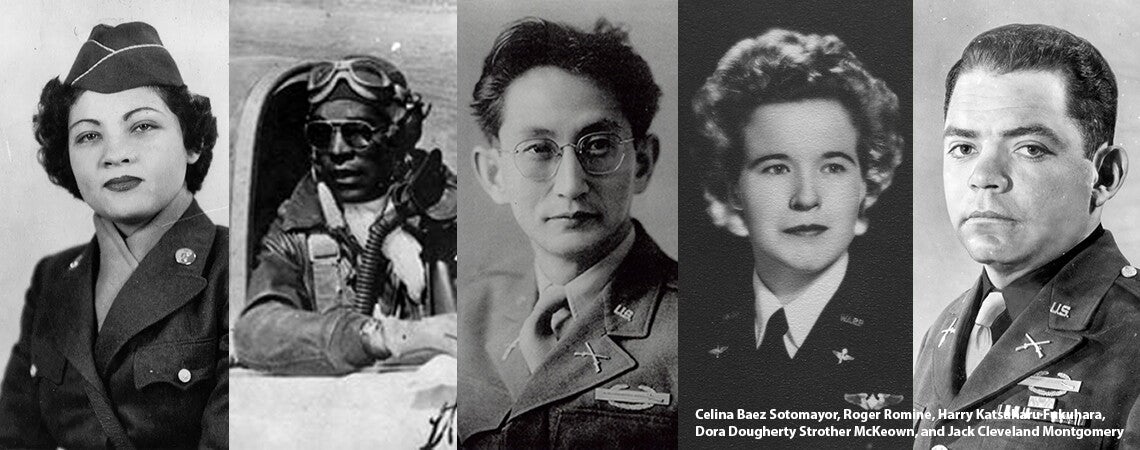

For most Americans, the sacrifices made by the men and women in the military services command respect and admiration. Too often those who served had to overcome racial or gender prejudice within the military, but they persevered because of a common desire to be of service to their country in wartime. Although their bravery was ultimately honored with medals by the military and with recognition by the US government, too few of these veterans are known to the general public. In this issue of History Now, we offer the personal stories of five men and women who overcame these racial and gender prejudices to emerge as true American patriots.

In “‘Courage to Face the Unknown’: The World War II Service and Legacy of Celina Baez Sotomayor,” Elizabeth R. Escobedo gives readers a biographical sketch of Celina Baez Sotomayor, the mother of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Born in Puerto Rico, Celina Baez was orphaned by the age of nine. She grew up in her older sister’s home but escaped the poverty of her existence by spending time in the local library, reading. She dreamed of an opportunity to make a better life and, when the Women’s Army Corps came recruiting in 1944, she applied to serve. She was only seventeen, but lied about her age in order to compete against more than 1500 applicants for one of the 200 spots allotted to Puerto Rican women by the WACs. Prejudice against these Spanish-speaking women, who were assumed to be less reputable than their mainland counterparts, meant that the tests Celina endured were rigorous. However, she was accepted and assigned to one of the segregated Puerto Rican units stationed in New York City. Her job was to work in the Post Office of the Port of Embarkation of the Army Transportation Corps, helping to sustain troop morale by keeping soldiers in touch with loved ones while they were overseas. When her military service ended, Celina Baez resolved to stay in New York City and here she married Juan Luis Sotomayor. Sonia completed high school and went on to become a practical nurse. When her husband passed away in 1964, she raised her two children, Sonia and Juan, as a single mother. Celina returned to school for her nursing degree and became the emergency room supervisor at Prospect Hospital. After fifty years in New York City, the widowed Mrs. Sotomayor married again and the couple moved to Florida. At the age of ninety-two, she stood beside her daughter Sonia as she was sworn in as the first Latina Supreme Court justice. Sonia Sotomayor has acknowledged the importance of her mother’s emphasis on education and a strong work ethic in her own success. Celina Baez Sotomayor is buried in South Florida National Cemetery in Lake Worth, Florida.

Pamela Rotner Sakamoto’s essay, “Harry Katsuharu Fukuhara: A Life of Service in War and Peace,” tells the story of a nisei, a second-generation Japanese American who, like 120,000 other ethnic Japanese, was interned during World War II. With his sister and niece, Harry would end up in a barren camp on an Indian reservation in Arizona. Despite this injustice, when he saw a chance to join the military as a bilingual interpreter and translator, Harry signed up. He was motivated, Sakamoto explains, by a notion of service based on his pride as an American. While patriotism was his prime motivation, he was also moved by a fierce desire to escape life in the internment camp. He assumed he would be assigned to a government office where he would translate captured documents, but he was dispatched to the Pacific front, serving with White units as they island-hopped closer and closer to Japan. He found himself in the jungles of New Britain and New Guinea, always under risk of friendly fire because of his race. His work interrogating Japanese POWs yielded up valuable information, but the Army was slow in promoting him. He was finally commissioned a lieutenant in the summer of 1945. In an ironic twist of fate, he avoided having to confront two of his brothers who were serving in the Japanese military when the US dropped the atomic bombs that ended the war. However, his mother and a third brother died in the bombing of Hiroshima. Despite this tragedy, Harry remained in the US Army during the occupation of Japan. He was inducted into the US Military Intelligence Hall of Fame in 1988 after forty-eight years of service. He received awards from the emperor of Japan and from the US president, and after he died at the age of ninety-five, he was commemorated by Military Intelligence with a hall at its headquarters named in his honor. Harry Katsuharu Fukuhara is buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery in California.

Tom Holm offers us an account of a Cherokee soldier in his essay, “Jack Cleveland Montgomery: Peace to War and Back Again.” Holm ponders why Montgomery, who saw combat, witnessed death, and was himself wounded twice in WWII, escaped the emotional problems associated with PTSD. In fact, Montgomery rose from life in an impoverished town in Oklahoma to become a national hero. Unlike a fellow Cherokee serviceman, Ira Hayes, Montgomery had the advantage of a college education and a stint in the Army in the European theater. His wartime service began after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and, after training, he and his Army division were assigned to North Africa. He soon became part of the assault force in the invasion of enemy-held Sicily. He was awarded the Silver Star for bravery in the fighting around Benevento, Italy. In the fighting near Anzio, Montgomery, now a lieutenant, distinguished himself despite being severely wounded. He was shipped home for the operations needed to heal his wounds. He received the Medal of Honor for his bravery and retired from the Army to work for the Veterans Administration. The state of Oklahoma and the Italian government awarded him honors, as did the Cherokee Nation. He died in 2002 and is interred at Fort Gibson National Cemetery in Oklahoma. He spent his entire life in service to his country and to his fellow veterans, drawing emotional strength from his Cherokee upbringing and from his identification with his fellow servicemen.

In “The Life and Death of Roger Romine: A Tuskegee Airman Gone Too Soon,” historian Lisa Bratton narrates the career of a pilot that ended tragically. Roger Romine was born in Oakland, California, in 1920, the son of a dining car waiter and a homemaker. He was in college in 1942, but registered for the draft that February. As a Black man, he trained at Tuskegee Army Airfield and, on the completion of his training, he held the rank of lieutenant. In 1944, he was stationed in Italy, where he shot down enemy aircraft that July and October. Professor Bratton learned of Romine during her years as a member of a five-person team that collected more than 800 interviews from surviving Tuskegee Airmen in the early twenty-first century. From these interviews, she learned that Romine had met his untimely death in a freak accident on the ground. A local Italian farmer wandered onto the airstrip with his herd of sheep, causing Romine to divert his plane into the mud on the side of the runway. A second pilot took off, hit the sheep, veered, and rammed into Romine’s plane. The explosion from the full tanks of gas that followed killed Romine. He died on November 16, 1944, and is buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery.

In her essay, “Dora Dougherty Strother McKeown, Women Airforce Service Pilot in World War II,” Katharine Landdeck tells the story of a daughter of a US Army veteran who dreamed of being a pilot. She got her chance in 1942 when the US was desperate to find pilots who could ferry warplanes from the factory to the coast where they could be put on ships or flown overseas for the bomber pilots. Although the head of the US Army Air Force had his doubts that women would be strong enough to fly military planes, he agreed to enlist them. Dora quit college, signed up, and was one of 1,830 women out of the 25,000 who applied to be admitted for training. Over the year she learned how to tow targets behind a dive bomber, to operate new secret radio-controlled planes, and to pilot a new, high-altitude plane called a B-52. Unfortunately, some male pilots resented the “incursion” of women into their realm, and women were forced out of this B-52 mission. In December 1944, the WASP [Women Airforce Service Pilot] division was disbanded and the female pilots sent home. Dora returned to college. In 1947, she joined the newly independent US Air Force as a reservist, but never flew for the military again. In the 1970s Dora was one of the leaders of a movement to get official recognition for the work WASPs had done during the war and to be considered veterans. Senator Barry Goldwater championed the cause, and in 1977 the WASPs were formally recognized as veterans. They were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2009. Dora died in 2013 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

As always, History Now provides its readers with additional materials on the issue’s topic. This issue includes an array of educational resources from the archives of the Gilder Lehrman Institute, including previously published History Now essays on World War II and soldiers’ lives, videos featuring leading historians, and spotlighted primary sources from the Gilder Lehrman Collection. The issue’s special feature is a set of three recent episodes of the Institute’s Book Breaks series focused on the legacies of those who served in World War II:

- “Bridge to the Sun: The Secret Role of the Japanese Americans Who Fought in the Pacific in World War II” with Bruce Henderson

- “Earning Their Wings: The WASPs of World War II and the Fight for Veteran Recognition” with Sarah Parry Myers

- “Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad” with Matthew F. Delmont

Nicole and I wish all of our subscribing teachers a rewarding remainder of the school year and a restorative summer vacation afterward. You and your colleagues help us ensure that the next generation will honor the past as it builds the future.

Carol Berkin, Editor, History Now

Presidential Professor of History, Emerita, Baruch College & the Graduate Center, CUNY

Nicole Seary, Associate Editor, History Now

Senior Editor, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Melissa Reyes, Contributing Editor, History Now 70

Dartmouth College, Class of 2025