Teaching Civics through History

In this unit, students will develop knowledgeable and well-reasoned points of view on the history of free speech in the United States.

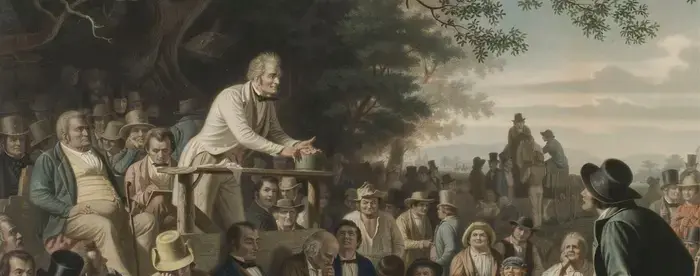

Image Source: Stump Speaking by George C. Bingham, published by Goupil & Co., New York, 1856 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC04075)