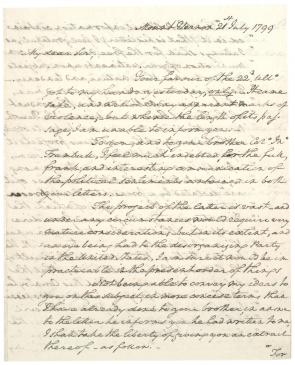

Washington on a proposed third term and political parties, 1799

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by George Washington

By 1798, George Washington had led America to victory in the Revolution, helped create the American government, and served two terms as the nation’s first president (1789–1797). He was called back to service, though, by President John Adams, who offered Washington a commission as chief officer of the US Army in July 1798 to help plan for possible conflict with the French. Washington reluctantly accepted.

By 1798, George Washington had led America to victory in the Revolution, helped create the American government, and served two terms as the nation’s first president (1789–1797). He was called back to service, though, by President John Adams, who offered Washington a commission as chief officer of the US Army in July 1798 to help plan for possible conflict with the French. Washington reluctantly accepted.

A year later, in June 1799, Jonathan Trumbull Jr., the governor of Connecticut who had served as Washington’s military secretary during the Revolution, wrote to urge him to run for a third term as president. "Election of a President is near at hand," Trumbull wrote, "and I have confidence in believing, that, should your Name again be brort up . . . you will not disappoint the hopes & Desires of the Wise & Good in every State, by refusing to come forward once more to the relief & support of your injured Country." Trumbull continued, writing that unless Washington sought the presidency, "the next Election of President, I fear, will have a very illfated Issue."[1]

Washington had several reasons for not running again. There was his promise not to seek unfair power as a government official and his desire to avoid being, as he wrote to Trumbull, "charged . . . with concealed ambition." There was also his "ardent wishes to pass through the vale of life in retiremt, undisturbed in the remnant of the days I have to sojourn here." Washington’s early promise and the lure of retirement were reasons for his declining to seek a third term.

Perhaps even stronger than those factors were Washington’s feelings about the country’s heated political climate. "The line between Parties," Washington wrote Trumbull, had become "so clearly drawn" that politicians would "regard neither truth nor decency; attacking every character, without respect to persons – Public or Private, – who happen to differ from themselves in Politics." Washington wrote that, even if he were willing to run for president again, as a Federalist, "I am thoroughly convinced I should not draw a single vote from the Anti-federal side." For Washington, the nation’s political parties had soured discourse and created a climate in which, as he predicted in his 1796 farewell address, "unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government." Referring to the Democratic-Republicans, Washington wrote, "Let that party set up a broomstick, and call it a true son of Liberty, a Democrat, or give it any other epithet that will suit their purpose, and it will command their votes in toto!"

George Washington was never a man to shirk responsibility. Though he might have liked nothing better than to retire to Mount Vernon after the Revolution, he was, as he wrote Trumbull, always ready to "render any essential service to my Country," having served, after the American Revolution, in the Constitutional Convention, two terms as president, and again as commander in chief of the Army. By 1799, though, Washington was through with elected office despite the urging of those who knew him. "Prudence on my part," he told Trumbull, "must arrest any attempt of the well meant, but mistaken views of my friends, to introduce me again into the Chair of Government."

A full transcript is available.

[1] Jonathan Trumbull Jr. to George Washington, June 22, 1799, in The Papers of George Washington, W. W. Abbott, et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987– ), Retirement Series, 4:144.