Surrender of the British General Cornwallis to the Americans, October 19, 1781

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Lord Cornwallis

These three documents—a map, a manuscript, and a print—tell the story of the surrender of British commander Charles Cornwallis to American General George Washington. In October 1781, the successful siege of Yorktown, Virginia, by General Washington in effect ended major fighting in the American Revolution. The American Army and allied forces defeated a British force there under Lord Charles Cornwallis, and on October 17, Cornwallis raised a flag of truce after having suffered not only the American attack but also disease, lack of supplies, inclement weather, and a failed evacuation.

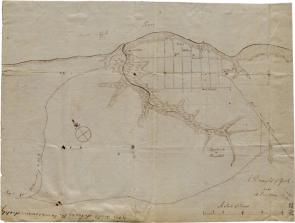

The map shows what Yorktown looked like before British military fortification. It displays key roads and buildings, but there are no fortifications or regimental positions shown. The map also features an intriguing endorsement: "You will deliver the town immediately," penned apparently in haste in what appears to be Cornwallis’s hand, meaning it was probably created just before the British captured and began fortifying Yorktown in summer 1781.

The map shows what Yorktown looked like before British military fortification. It displays key roads and buildings, but there are no fortifications or regimental positions shown. The map also features an intriguing endorsement: "You will deliver the town immediately," penned apparently in haste in what appears to be Cornwallis’s hand, meaning it was probably created just before the British captured and began fortifying Yorktown in summer 1781.

On October 6, allied forces under Washington began digging the first siege line, and on October 9 the fighting began. British forces were cut off from their supply lines, and—running out of ammunition, suffering high casualties—Cornwallis attempted to evacuate his troops. The evacuation was thwarted by stormy weather, however. On October 17, Cornwallis was forced to seek a truce and cease-fire to negotiate his army’s surrender.

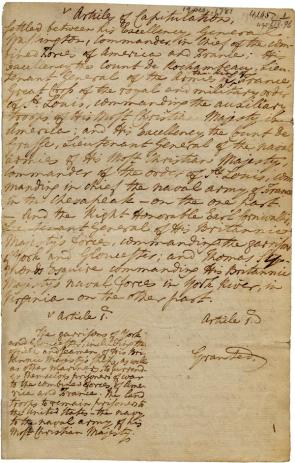

Cornwallis and Washington began negotiating the terms of British surrender in their correspondence of October 17, 1781. Cornwallis knew that his soldiers had been devastated by continual artillery fire from Knox over several weeks, that Clinton’s reinforcements were weeks from arriving, and that a renewal of hostilities would cause more death and bloodshed. This copy of the final list of terms, known as the Articles of Capitulation, was created by Samuel Shaw, Henry Knox’s aide-de-camp.

Cornwallis and Washington began negotiating the terms of British surrender in their correspondence of October 17, 1781. Cornwallis knew that his soldiers had been devastated by continual artillery fire from Knox over several weeks, that Clinton’s reinforcements were weeks from arriving, and that a renewal of hostilities would cause more death and bloodshed. This copy of the final list of terms, known as the Articles of Capitulation, was created by Samuel Shaw, Henry Knox’s aide-de-camp.

The final Articles of Capitulation reflect the concerns and compromises of the two sides over the surrender of British troops and the treatment of loyalists. Article 3 states that: "the garrison of York will march out to a place to be appointed in front of the posts, at two o’clock precisely, with shouldered arms, colors cased, and drums beating a British or German march. They are then to ground their arms, and return to their encampments, where they will remain until they are dispatched to the places of their destination."

A second major bone of contention for the British involved the treatment of loyalists. Washington tacitly acknowledged Cornwallis’s right to facilitate the escape of loyalists and American deserters in Article 8 by allowing Cornwallis unregulated use of the sloop Bonetta for carrying dispatches to British headquarters in New York City: "The Bonetta sloop-of-war to be equipped, and navigated by its present captain and crew, and . . . to be permitted to sail without examination."

On the morning of October 19, Cornwallis signed two copies of the Articles, which were returned to Washington’s headquarters. As if to instruct posterity as to where this victory was really achieved, Washington added a short paragraph at the end: "Done in the trenches before York, October 19th, 1781."

A full transcript is available.

On October 19, 1781, at two o’clock that afternoon, the surrender ceremony commenced. This print, an 1845 lithograph, depicts the surrender at Yorktown. The print shows a defeated Lord Cornwallis surrendering his sword to General Washington. A regal and serious Washington stands with open hands ready to accept Cornwallis’s offering. This transaction, however, was not the one that actually took place. In reality, Cornwallis chose not to participate in the surrender, citing illness and leaving General Charles O’Hara to lead the British troops. Washington, refusing to accept the sword of anyone but Cornwallis, appointed General Benjamin Lincoln to accept O’Hara’s sword. Though Cornwallis did not really present his sword to Washington at the surrender, this print captures, if not a true moment, a patriotic feeling forged by the end of Revolutionary hostilities and the birth of a new nation from the ashes of war.

On October 19, 1781, at two o’clock that afternoon, the surrender ceremony commenced. This print, an 1845 lithograph, depicts the surrender at Yorktown. The print shows a defeated Lord Cornwallis surrendering his sword to General Washington. A regal and serious Washington stands with open hands ready to accept Cornwallis’s offering. This transaction, however, was not the one that actually took place. In reality, Cornwallis chose not to participate in the surrender, citing illness and leaving General Charles O’Hara to lead the British troops. Washington, refusing to accept the sword of anyone but Cornwallis, appointed General Benjamin Lincoln to accept O’Hara’s sword. Though Cornwallis did not really present his sword to Washington at the surrender, this print captures, if not a true moment, a patriotic feeling forged by the end of Revolutionary hostilities and the birth of a new nation from the ashes of war.